Home

Magna Carta at Harvard Law: A new discovery, a rich history

Harvard Law Today takes a closer look at the history of Magna Carta at Harvard Law.

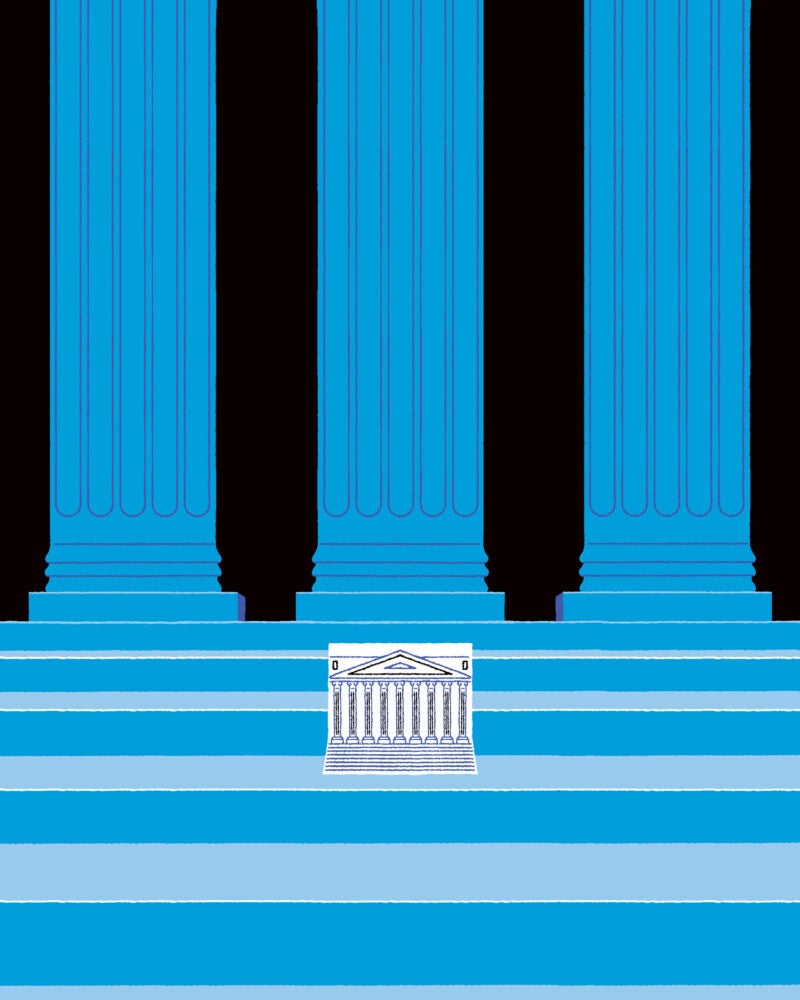

The Courts of Last Resort

As the U.S. Supreme Court embraces federalism, are state supreme courts becoming the new power centers?

Featured Areas of Interest

- Administrative and Regulatory Law

- American Indian Law

- Animal Law

- Antitrust

- Arts, Entertainment, and Sports Law

- Bankruptcy and Commercial Law

- Children and Family Law

- Civil Litigation

- Civil Rights

- Conflict of Laws

- Constitutional Law

- Criminal Law and Procedure

- Contracts

- Comparative Law

- Corporate and Transactional Law

- Courts, Jurisdiction, and Procedure

- Disability Law

- Education Law

- Election Law and Democracy

- Employment and Labor Law

- Environmental Law and Policy

- Finance, Accounting, and Strategy

- Financial and Monetary Institutions

- Gender and the Law

- Health, Food, and Drug Law

- Human Rights

- Immigration Law

- Intellectual Property

- International Law

- Jurisprudence and Legal Theory

- Law and Economics

- Law and Philosophy

- Law and Political Economy

- Law and Religion

- Leadership

- Legal History

- Legal Profession and Ethics

- LGBTQ+

- National Security Law

- Negotiation and Alternative Dispute Resolution

- Poverty Law and Economic Justice

- Private Law

- Property

- Torts

- Race and the Law

- State and Local Government

- Tax Law and Policy

- Technology Law and Policy

- Trusts, Estates, and Fiduciary Law

- More

500+ Courses & Seminars

47 Clinics & Student Practice Orgs

88 Student Organizations

Limitless Possibilities