By Clea Simon

Via Harvard Law Today

Harvard Law School lecturer Jim Tierney, Maine’s former attorney general, developed a new open casebook to help teach law students about the role of state attorneys general.

State attorneys general occupy a unique place in American jurisprudence. All 13 of the original American colonies had an attorney general, as do all 50 states as well as the District of Columbia today, and they collectively try more cases before the U.S. Supreme Court than any legal entity except for the U.S. Department of Justice.

However, the office is not a monolith: The differences in the state laws that each enforces as well as in the varying relationships with governors, legislatures, and other institutions set each state attorney general apart. But thanks to Harvard Law School lecturer James E. Tierney, the former state attorney general of Maine, a new open casebook (or collection of cases and related material) enables attorneys general to share their experiences in real time — and provides a living text for law school students seeking to understand this definitively American structure.

“When we talk about the office of the state attorney general, we’re talking about the big cases of our time,” said Tierney, speaking from his home in Maine. With the standard law school curriculum focused on the federal government, many students — and law school graduates — “find the state side incomprehensible.”

It’s a gap Tierney is intent on filling. Citing cases ranging from the Trump administration-era travel ban and the Affordable Care Act to current suits pending over abortion, he said: “Students need to understand what’s going on the state level. Attorney general offices are bringing these cases, and how they bring them, how they think about them, how they staff them, how they conceptualize them, whether the ethics involved — that’s what I teach.”

The casebook, explained Tierney, grew out of his own experience. Following a decade as the Maine attorney general, and a total of roughly 40 years “studying and participating in the decision-making of attorneys general and their staff,” he began teaching, first at Columbia University and then at Harvard Law, where he also serves as director of the Harvard Attorney General Clinic. That’s when he ran into a roadblock: “There was no textbook for teaching about state attorneys general because it hadn’t been taught before.”

So, he began compiling cases, articles, and commentary for a syllabus. His collection was so comprehensive that he was approached by a commercial textbook publisher. But while Tierney understood the need for such a text, he recalled another option — an early experiment with open-source material that he had tried roughly ten years before. “The technology wasn’t there yet,” he recalled. With that early trial in mind and seeing the need for a course like his to be more widely taught, he revisited the technology, curious to see what might be possible.

What he found was much improved — and designed specifically for texts like his. Over the previous two decades, the Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society, with support from the Harvard Law School Library, had been working on a web-based platform for creating, editing, organizing, consuming, and sharing course materials. That platform — H2O — took a huge leap forward in 2018 when the team directly integrated caselaw from the Caselaw Access Project. This meant that authors could pull the vast majority of U.S. caselaw into their books for free and annotate those cases how they want. Now maintained by the Library Innovation Lab at the Harvard Law School Library, H2O is dedicated to expanding the bounds of open-access legal education. In other words, it was perfect for Tierney’s project.

“The topic of state attorneys general should absolutely receive more coverage in law school, and we’re delighted H2O could play a part,” said Jack Cushman, director of the Library Innovation Lab. “The Harvard Law School Library built H2O exactly for this purpose — so professors like Jim could make casebooks on important under-taught subjects and spread their ideas to law schools across the country. We wanted to help professors share, use, and build on each other’s work, and Jim has created the perfect blueprint for others to follow.”

When the pandemic closed everything down in early 2020, Tierney got to work, “drilling down” to write and organize what would become a comprehensive and inclusive text covering all aspects of the role of state attorneys general. The resulting beta version gave him something to teach from; a living, growing syllabus, whose open-source nature allows him to work out any issues. Available online as open-source text, the casebook is accessible to all and, as Tierney pointed out, “very transportable.”

The current casebook — no version can be called “final” — contains federal and state statutes and case law, law review and descriptive articles from a variety of sources, and hypotheticals that describe the nature and function of the office of state attorney general. In many cases this is the first time the material has been gathered in one place. As Tierney explains, “The numerous hypotheticals drafted primarily by long time co-teacher and former Maine Solicitor General Peter Brann are drawn from actual cases that, because of their nature, have not been studied or, in most cases, ever made public.”

Those cases are continuously updated. One advantage of the open-source format is that users — notably law professors and state attorneys general and those in their offices — can add and edit material, from new developments in cases to intriguing commentary. “I may be the premier editor,” said Tierney. “But I want others to edit it. I want them to take it and run with it. We are in about 20 law schools and are growing in large part because of this text.”

“The technology is really great,” agreed Nick Smyth ’09, senior deputy attorney general in the Pennsylvania Office of the Attorney General. Smyth, assistant director for consumer financial protection, last year began teaching a course on state attorneys general at the University of Pittsburgh School of Law. “It’s very current. Unlike a traditional casebook, it can be edited as things are coming out.” Most casebooks, he noted, are typically updated only every few years, with each new edition taking months to revise and then publish.

In addition, said Smyth, the technology made it easy to adapt Tierney’s syllabus for his own class. “I made some modifications to make it as relevant as possible to students here in Pittsburgh. It’s just very nice to be able to copy over things that he has on his casebook, and when he updates it, it’s very easy to grab updates.” As he first began teaching this year, Smyth noted, “I was updating and modifying the syllabus as I went along.”

The online nature of the casebook has another benefit: All this material would be unwieldy as a traditional textbook. But as a virtual book, there’s no pressure to cut pages. The cumulative result is more than even Tierney can teach. “There’s enough material in there to teach five courses,” agreed Tierney. But this comprehensive nature adds to its flexibility, he pointed out, ideally making it useful to a wide variety of law schools. “It functions in a way that professors who want to use it can say, ‘Okay, I want to teach state anti-trust or the role of the AG and police misconduct or the role of the AG and the environment. All of the key issues of our time.”

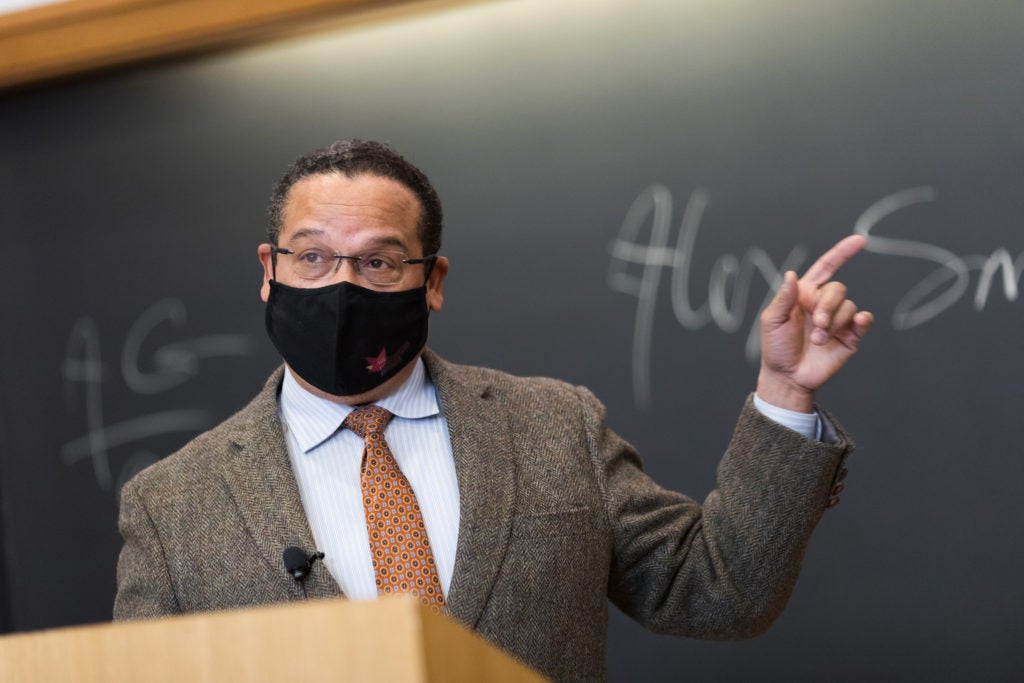

For his class on Public Interest Advocacy and the State Attorney General, which he teaches at the University of Minnesota, Minnesota State Attorney General Keith Ellison focuses on 12 topics. “The casebook has more topic areas than I can even assign,” he said. He’s fine with that: “It gives me options.”

William McCollum, who served as Florida’s attorney general from 2006 to 2011, uses the casebook as a guide to creating his own Florida-centric curriculum for the intensive one-week course he teaches annually at the University of Florida School of Law. “Anyone teaching this course in any state should, first and foremost, look at their own state and understand the distinctions. But the powers are similar in many cases,” he said. As an example, he noted, “Pretty much every state has its own antitrust laws.”

Smyth agrees. “We can teach the concepts and the mechanics of a consumer protection investigation and litigation. It’s very similar across states,” he said, noting that the breadth of the cases available also enables teachers to focus on legal basics. “It translates very easily.”

The diversity of material in the casebook plays a crucial role for McCollum. His course’s short, intensive nature — three hours a day for four days and two hours on the fifth day — severely limits what he can teach. With that in mind, “I’m not going to assign a case every time,” he said. Most recently, he used an article by New York Times investigative reporter Eric Lipton, which he found in the casebook. “I’m not going to go into depth every time,” he acknowledged. An article summarizing a case can be a useful alternative, “showing what the point is.”

The wealth of material also pays off for understanding multi-state cases, explained Smyth. He cites a recent case in which Navient, one of the nation’s largest student loan servicers, was sued for predatory subprime loans. The initial suit brought by five states – Pennsylvania, Washington, Illinois, Massachusetts, and California – eventually expanded to a coalition of 39 attorneys general, winning a settlement that included $1.7 billion in debt cancellation and $95 million in restitution. Pennsylvania borrowers alone won over $70 million in relief.

“We were all in close contact over the course of the litigation, and we ended up all settling together,” recalled Smyth. “Even though we were each in different state courts (and Pennsylvania actually was in a federal court), we were facing slightly different procedural rules, and the underlying case law was maybe a little different, the substance — the wrongdoing by the company Navient — was the same nationwide.”

Such cooperation is possible because of the nature of the position. As Ellison explained: 43 attorneys general are elected, and “while another five might be appointed by the governor of the legislature, they can only be dismissed for cause.” As a result, he pointed out, “There is a lot of autonomy among state attorneys general. We have different degrees of criminal jurisdiction, but all of us as statewide officeholders look to play critical role.”

Thanks to the open casebook, understanding how attorneys general play that role — and how they work together — is now easier to understand. And to teach.

“It’s an easy reference source,” concluded McCollum. “There’s very little like this out there.”

Tierney himself continues to teach, and he points to the long waitlist for both the fall and spring semesters as proof of the course’s continued relevance. “The state is where public policy issues are headed,” said the lifelong Mainer. “The whole world is pivoting back to the states.”