Fifty years ago, the Massachusetts corrections commissioner handed the keys to the men incarcerated at Walpole State Prison. They ran the facility for two months — to prove to the world that prisons shouldn’t exist at all.

By Julian J. Giordano and Benjy Wall-Feng

Via The Harvard Crimson

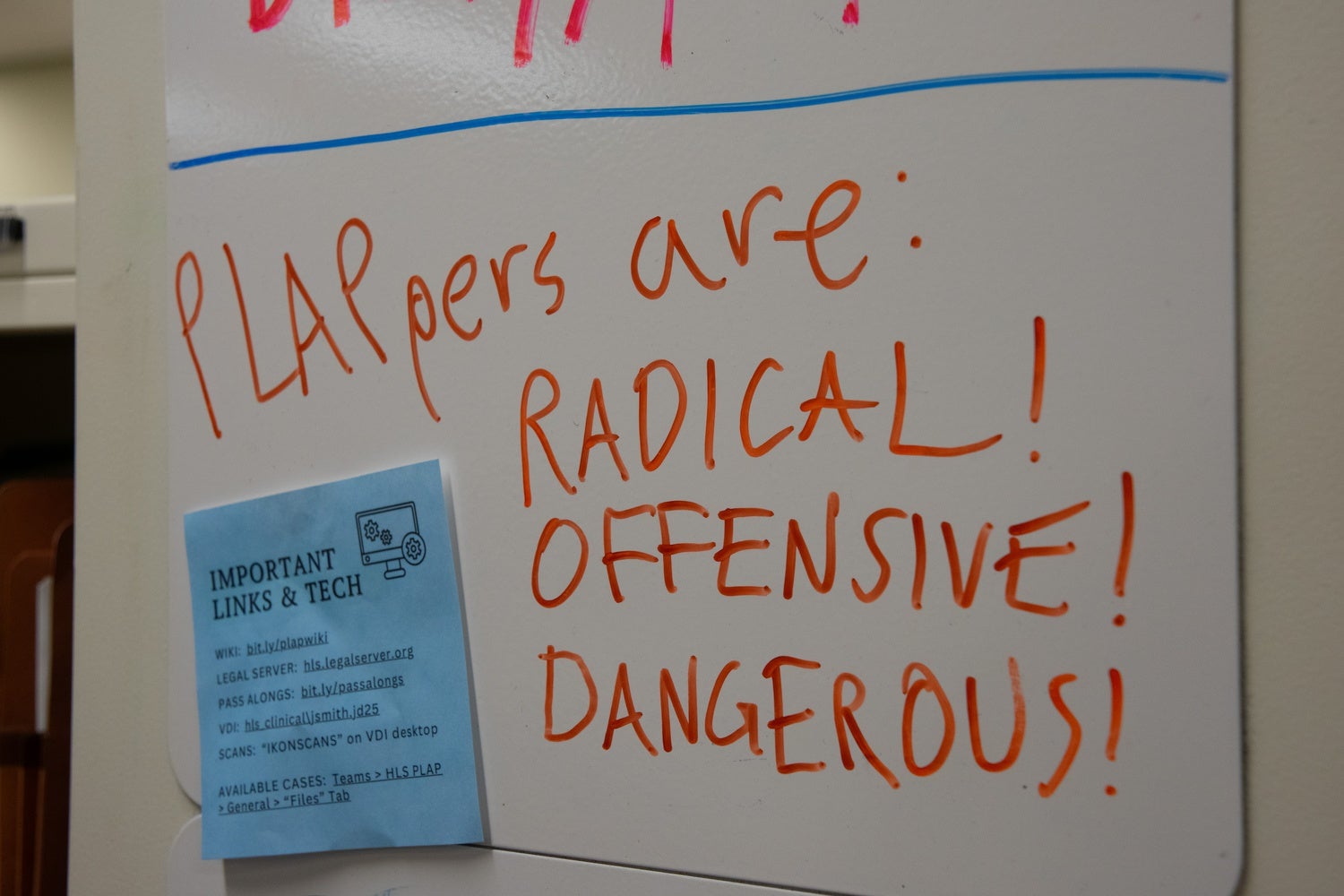

As reforms were rolled back, a group of radical Harvard Law students took it upon themselves to serve as lawyers without licenses for prisoners, representing them in disciplinary and parole hearings without faculty supervision. They called themselves the Prison Legal Assistance Program, or PLAP.

In 1972, two years after their founding, the Department of Correction contacted them, asking if they could mediate a prisoner uprising at MCI-Concord. The “PLAPpers,” as they called themselves, drove out to Concord and walked around the cell blocks, working with the men incarcerated there to facilitate a peaceful resolution.

Over the next couple decades, PLAP sent students to prisons across Massachusetts to represent thousands of prisoners in disciplinary and parole hearings that they would otherwise be left to go through alone.

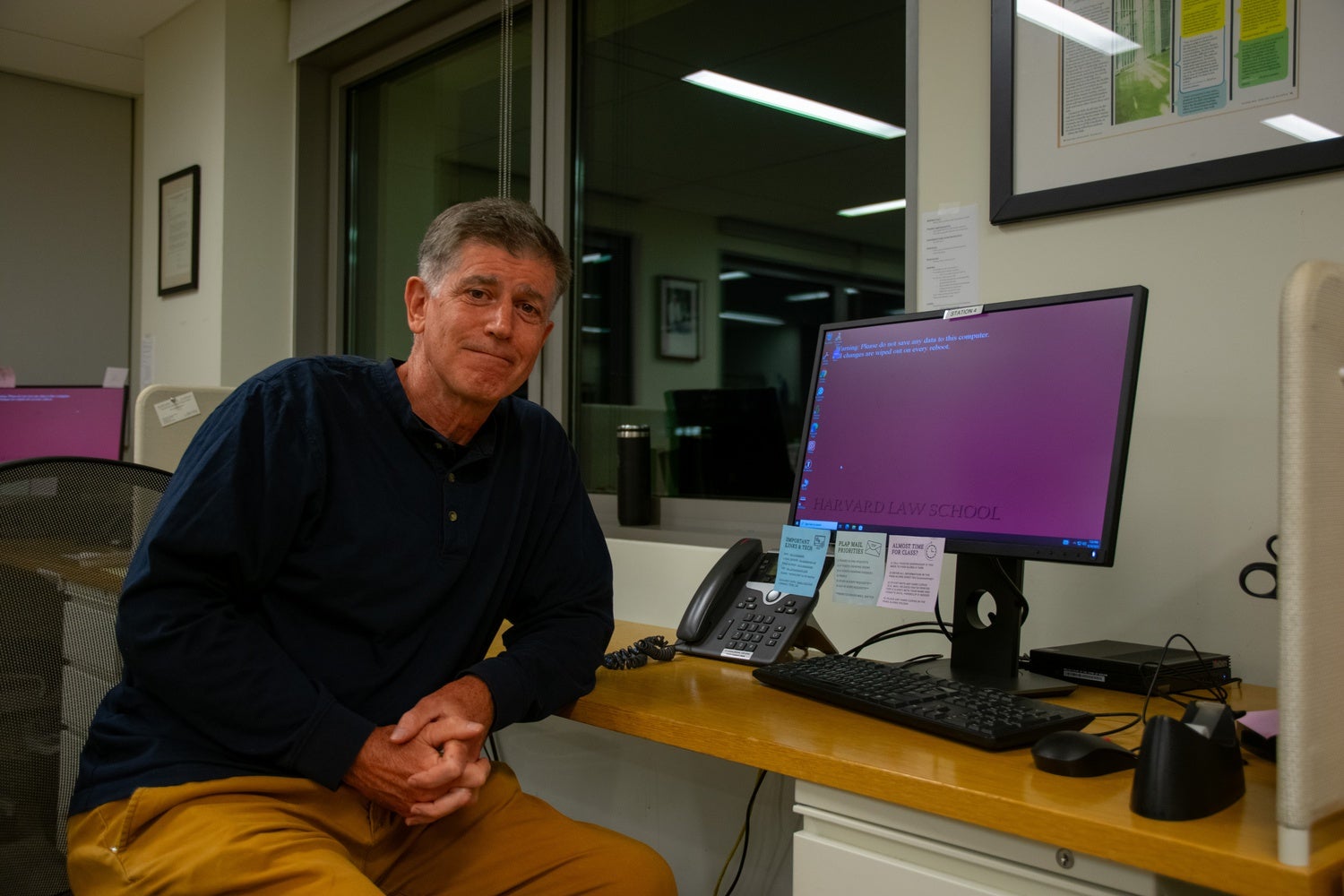

John D. Fitzpatrick was a PLAP member from 1984 to 1987, and has been a clinical instructor at PLAP since 1998, but his connection to Walpole dates back even earlier: His mother developed an autonomous health collective there in the 1970s as part of her dissertation, teaching men medical skills so that they could tend to each other.

Speaking rapidly, Fitzpatrick tells us about the violence that Walpole descended into through the ’70s and early ’80s. He recalls his mother’s collective being immediately crushed after she left the prison — the prison administration was “very skittish about empowering prisoners to any extent at all.” When he first visited Walpole as a law student in 1984, there were what he calls “dog cages” for prisoners in the solitary confinement block, as well as a complete lack of heating or air conditioning and rats running around. “It was medieval,” he says.

Fitzpatrick tells us that PLAP’s presence in prisons provides a form of accountability. As outside observers bearing witness to what is taking place, he says, student volunteers help ensure that the institution adheres to legal norms.

There are other prison assistance programs at law schools across the country, but none of them have been around as long as Harvard’s, and few have the same scope. In the past 50 years, the program has gone from having fewer than 20 active members to having a current team of more than 120 members serving all 14 Massachusetts corrections facilities, with each student taking at least one case per year.

Still, the structure of the program has changed very little. At the PLAP office, students pick up calls from prisoners, writing down details and hearing dates to flow into a case management system. Students then pick up and prepare cases before driving to meet their client in prison. Jason Adkins, who volunteered with PLAP in the late ’80s, remembers working with three clients to have them be granted parole — one of them without forcing the client to confess to the alleged crime, which is unusual for parole hearings.

Seeing the systemic injustices of prisons — often for the first time — shaped the way the students thought about their future careers in law. Some became reform activists and others vowed to never become prosecutors; some actually walked away with a stronger confidence in the need for prisons. All of the students described their experiences as rewarding.

Sandra Grannum, who volunteered with PLAP from 1983 to 1986, recalls learning “what it’s like when somebody really depends on you.”

“I don’t know that ever in my life I ever felt like that before, like I was the last hope,” she says.

While incarcerated men say they were grateful for representation from students in PLAP, representation was never guaranteed, often inconsistent, and sometimes unpredictable. The way the system was supposed to work, prisoners would leave their information with the PLAP hotline, and one student or another would eventually take the case.

That’s not how Dellelo remembers it.

“What the professors do is they take the card with information and they put it on the fucking board,” he says. “And if a student picks it, then they’ll come somehow talk to you. But they don’t, and what happens is you lose your appeal time ’cause you wait for some student, who you have no idea if they’re gonna take the damn thing, and if they don’t, you’re fucked.”

Dellelo adds, “You can’t do that to fucking people ’cause they’re losing their appeal rights, because you don’t want to get off your fucking ass.”

Harry Rouse IV, another former PLAP member, points out that Walpole, an hour’s drive away and inaccessible by transit, was difficult for students to get to. “Sometimes the dates didn’t work out. People didn’t have cars. It was hard to get to Walpole because it was square on the other side of Boston,” Rouse says. “To do it right took some time” — time the prisoners didn’t always have.

Many of the former PLAP members we spoke to told us the program was an unequivocal good. It was a place to make friends, learn valuable skills like cross-examination, and help people in need. For the people on the other side of the wall, though, Harvard students were only a small part of their experience — albeit with an outsized ability to alter their sentences.

Today’s PLAP student directors tell us that they’re always trying to do more. They now engage in impact litigation — pursuing civil suits that, for example, increase access to courts for incarcerated people — and have a team that does policy advocacy.

“This work is really radicalizing,” says Faith Blank, one of the directors. Her co-director Manvitha Kapireddy adds: “We’re really trying to have more guidance, more education on what abolition means, so that people can get there on their own.”

Contact Office of Clinical and Pro Bono Programs

Website:

hls.harvard.edu/clinics

Email:

clinical@law.harvard.edu