via Harvard Magazine

by JULIET ISSELBACHER

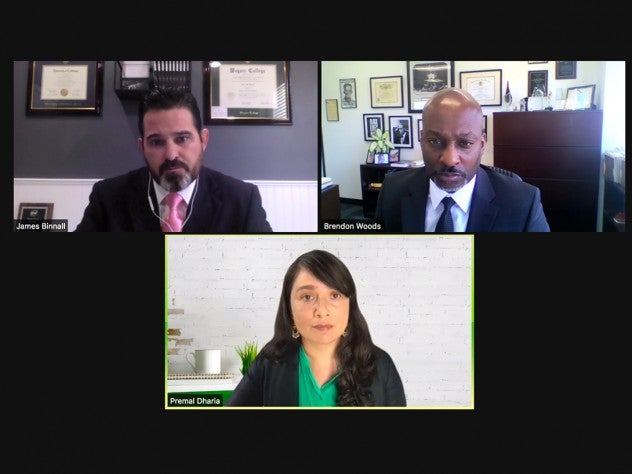

SHOULD CONVICTED FELONS BE ALLOWED to serve on juries, sitting in judgment on their fellow citizens? On June 2, Premal Dharia, inaugural director of Harvard Law School’s Institute to End Mass Incarceration, moderated a discussion of this question, at an event co-sponsored by the Radcliffe Institute between two invited speakers: Brendon D. Woods, the chief public defender in California’s Alameda County, and James M. Binnall, an associate professor of law, criminology, and criminal justice at California State University, Long Beach. Binnall is the author of Twenty Million Angry Men: The Case for Including Convicted Felons in Our Jury System (2021).

Binnall began his remarks by sharing that he is among the approximately “twenty million angry men” excluded from the country’s jury system. “In 1999, I caused the DUI wreck that claimed the life of my passenger, who was a college wrestling teammate of mine and my best friend,” he said. “I spent four years, one month, and six days in two maximum security prisons in southern Pennsylvania.”

Just six months after his release, Binnall began his first year of law school. In 2008, he was admitted to the State Bar of California. A year into a fledgling career of criminal-defense work, Binnall received a summons for jury duty and felt a “very strange sense of pride and privilege” stepping through the “attorneys only” entrance at the courthouse. That feeling quickly faded in embarrassment, however, when he was informed that his prior felony conviction rendered him permanently ineligible for jury service under the then-existing California state law.

Binnall soon learned he was far from alone. Individuals with a felony conviction face restrictions on jury service in every state except Maine, and they are permanently excluded from participation in more than half the states in the nation. California has since changed its law.

“Courts and lawmakers allege that those with a felony conviction would jeopardize the jury process because they purportedly lack the requisite character to serve, and/or harbor an inherent bias, making each adversarial to the state,” Binnall explained. But in researching his recent book, he found that these justifications are empirically unsound.

Binnall said the “most damning evidence against exclusion” comes from his mock-jury experiment, in which he studied how those with felony convictions approached simulated service. This cohort of convicted felons was “thoughtful” and “considerate” in its participation, recalling more case facts and speaking at greater length during deliberations than the non-felon control group. Furthermore, the former felons “demonstrated a normal distribution of pretrial biases.”

Asked by Dharia to elaborate on this “normal distribution,” Binnall explained that there was no statistically significant difference in bias between law students and individuals with past felonies. “Should we exclude all law students from jury duty as well?” he asked rhetorically. He went on to note that the pro-defense bias shared by law students and formerly incarcerated people was inversely matched by an equally strong pro-prosecution bias in law enforcement personnel.

While Binnall focused on why the justifications for jury exclusion are fallacious, Woods turned the audience’s attention to how these justifications are propped up by racism and white supremacy.

“People of color make up about 30 percent of the U.S. population, and they account for 60 percent of those that are in prison. One out of five black men are in custody right now, as opposed to one out of every 106 white men,” Woods said. “With that incarceration of predominantly black and brown people comes the inevitable stripping of certain rights that a normal citizen would have.”

Until a 2019 bill reduced jury restrictions on felons in California, Woods said more than 30 percent of black men in his home state were barred from jury duty for life. The upshot of statistics like these is that many black people are denied a second right—the right to be judged by a jury of their peers.

“When I was a sophomore in college, my uncle got sentenced to 27 years in prison. And there wasn’t a single black person on the jury,” Woods recalled. “I do believe there is a reason and purpose” that explain “why these exclusions exist. And it goes back to history, it goes back to slavery, it goes back to when juries were comprised of all white men in order to convict black men.”

Looking forward, Dharia asked the speakers what the country can learn from Maine, which does allow former felons to serve on juries without restrictions. But Woods cautioned against affording the state trailblazer status. “Maine, I think, is, like, 1.2 percent black,” he said, suggesting that the state simply didn’t have the motive to impose these restrictions, given such a small black population.

In closing the discussion, Dharia asked Woods if he had any “parting words of wisdom” for aspiring activists.

“Don’t try to get out of jury service. Come, show up, do your part,” he answered. “If you care about ending mass incarceration, show up for jury service. If you care about some sort of racial justice or racial equity in the courts, show up for jury service.”

Filed in: Clinical Voices, Legal & Policy Work

Contact Office of Clinical and Pro Bono Programs

Website:

hls.harvard.edu/clinics

Email:

clinical@law.harvard.edu