via Harvard Magazine

by Lydialyle Gibson

Photograph courtesy of Harvard Law School

AMID THE PROTESTS last summer that followed George Floyd’s killing by Minneapolis police, three Boston City Council members proposed an ordinance to divert nonviolent 911 calls away from the Boston Police Department. Those calls—often involving mental-health emergencies, homelessness, substance use, and traffic accidents—would be dispatched to community-safety officials in non-law-enforcement agencies instead.

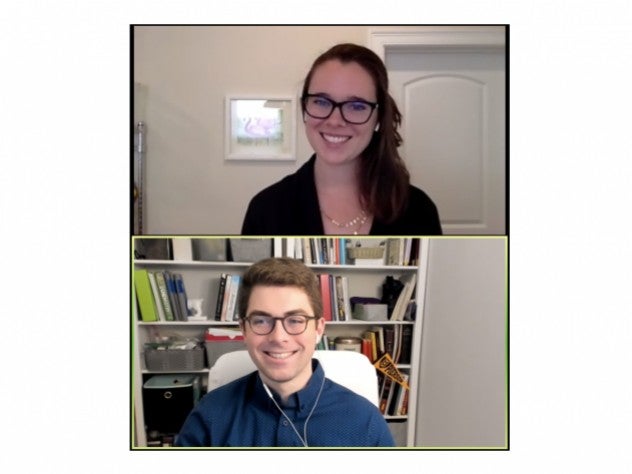

Last fall, Harvard Law School’s Negotiation and Mediation Clinical Program volunteered to help city administrators think through concrete possibilities for how to change public-safety procedures. Two law students, William Roberts and Anna Vande Velde, spent several months as part of the program’s Dispute Systems Design Clinic, researching other cities’ approaches and interviewing Boston-area city officials. The pair also studied the multiple ways Boston’s public-safety system intersects with other local factors: racial bias, income inequality, access to medical and mental-health care, pipelines to prison from school or foster care, and substance-abuse rates—to name only a few. The inquiry yielded a report, released late last week.

“We found a number of cities that were doing neat things,” says Roberts. In Texas, Houston and surrounding Harris County law enforcement officials have worked closely since the 1990s with a mental-health organization, the Harris Center, whose clinicians assist officers in responding to crises; clinicians themselves respond to mental-health emergency calls, and the organization serves as a crisis drop-off center for police officers bringing in people who need such support.

In Eugene, Oregon, the Crisis Assistance Helping Out On The Streets Program (CAHOOTS) has been operating for 30 years. Police dispatchers send unarmed medical and mental-health workers (without law-enforcement officers) in response to reports of mental-health crises, substance abuse, or homelessness. The CAHOOTS workers arrive wearing casual clothes in a van with a dove painted on the side, and are trained to handle a range of problems, from conflict resolution and suicide prevention to offering first aid or a ride to better-equipped services. In 2019, CAHOOTS responded to roughly 24,000 calls and requested police backup only 150 times.

Based on those examples—and similar collaborative efforts in more than a dozen other cities including Denver, New York, Washington, D.C., and Boston itself—Roberts and Vande Velde developed a series of recommendations that included: creating crisis drop-off centers; establishing a mechanism for follow-up on cases by mental-health or social workers; adding a mental-health question to the 911 dispatch script; creating a mental-health division within the police department itself; and requiring crisis intervention training for all officers. The report also spelled out a number of stakeholder groups whose input would be important in outlining reforms: police-reform advocates, police-department representatives, dispatch employees, the Boston Emergency Services Team, social workers and mental-health professionals, and local residents from communities that see disproportionate numbers of stops and arrests by law enforcement. Citing a successful program in Maryland, the report also recommended offering re-entry and mediation services to incarcerated people before their release from prison, to help them make connections with friends and family who will serve as supports, and to foster (sometimes difficult) conversations that will also help prepare them for life on the outside.

“A surprising and salient thing that kept recurring in our discussions with experts in other cities,” says Roberts, is the “incredibly broad range of skills that might be called on and needed” by first responders. Other cities’ reforms had broadened the training and tools available to their emergency-response systems.

He added that Boston has already begun to undertake some of these reforms. Mental-health clinicians accompany officers to some calls as part of the police department’s Co-Response Program, and there are less-formal collaborations as well. “Boston doesn’t need to reinvent its public-safety system,” he asserts. “The relationships and connections with mental-health organizations are there. What needs to happen, in our view, is a formalization of those connections, and a further expansion.”

The report’s other major component analyzed the effects of race and racism on how law enforcement is carried out in Boston. “That’s critical to consider in any public-safety reform,” Roberts says. “It’s something the experts and stakeholders we spoke with were very concerned about and felt would be necessary as Boston looks at its own system.”

Alexandra Natapoff

Photograph by Lydialyle Gibson

THE REPORT’S recommendations and Roberts’s observations closely echoed some of the remarks at a recent Law School panel discussion revolving around the work of Kreindler professor of law Alexandra Natapoff. Her 2018 book, Punishment Without Crime: How Our Massive Misdemeanor System Traps the Innocent and Makes America More Unequal, inspired a documentary released this year, Racially Charged: America’s Misdemeanor Problem. After an online screening last week, Natapoff moderated a conversation among panelists that included Suffolk County district attorney Rachael Rollins and Guggenheim professor of criminal justice Sandra Susan Smith (see Harvard Magazine’s profile in the forthcoming May-June issue).

Rollins lamented the “comorbidity factors” that often entangle people—including close members of her own family—in the criminal justice system: “substance-use disorder, mental health, food and housing insecurity, and other circumstances that are far beyond their control. We penalize people for being poor every single day.” Smith pointed to the growing body of research showing that “in high-crime communities, which are disproportionately low-income communities of color, police are doing more harm than good.” She argued for dramatically scaling back law enforcement in favor of alternative models of public safety (and like Roberts, she praised Oregon’s CAHOOTS program).

Sandra Susan Smith

Photograph by Lydialyle Gibson

“Very little of the time that police officers spend at work involves actual crime fighting,” Smith said, “and this is the case even in the most dangerous neighborhoods or communities. In Baltimore in 1999, the most violent and most addicted and most abandoned city in America, regular patrol officers spent 11 percent of their time on crime.” In other places, she added, it’s below 1 percent. Especially in communities that suffer from both overpolicing (excessive stops and arrests, unconstitutional searches, routine confrontations) and underpolicing (which leaves many crimes unsolved and residents without help when they need it), Smith said, “It makes sense to start to consider other options for achieving safety. And we have an abundance of research that shows directions that we can go.”

Filed in: Clinical Student Voices, Clinical Voices

Tags: Anna Vande Velde, Harvard Negotiation & Mediation Clinical Program, HNMCP, William Roberts

Contact Office of Clinical and Pro Bono Programs

Website:

hls.harvard.edu/clinics

Email:

clinical@law.harvard.edu