via The Hill

by LAURIE BEYRANEVAND AND EMILY BROAD LEIB

In the early months of the coronavirus pandemic, shocking images emerged from both ends of an American food system seemingly on the brink of collapse. Photos and videos of farmers dumping crops — perfectly good potatoes, squash and milk — appeared above articles about the rising “tsunamis” of food waste as food service buyers disappeared. Meanwhile, lines for food banks filled parking lots, circled around neighborhoods and shut down highways.

How is this possible? America’s food system has long been plagued by massive inefficiencies and injustices. They just weren’t quite so visible to all before now. Soaring rates of food insecurity, the exploitation of food workers, massive volumes of food waste, widespread nutritional deficiencies leading to alarming rates of diet related disease, the challenging economics of farming and disproportionate harm to underserved and Black, Indigenous and people of color (BIPOC) communities — all of these existed at near-crisis levels before the coronavirus first infected a single human. The virus and resulting public health measures simply brought these issues to the front burner and turned them up to a rolling boil.

The reasons that COVID-19 had our food system on the brink of collapse are the same ones that have allowed these inequalities and failures to persist for decades. Laws that govern the food system are piecemeal and incremental, our regulations entirely fragmented between dozens of agencies and departments across federal, state and local jurisdictions and our policymakers have entirely neglected taking any comprehensive, strategic and proactive approach to resolve them.

This fragmentation delivers a food system rife with inefficiencies and conflicts. We waste as much as 40 percent of the food produced in the U.S. while tens of millions of Americans go hungry. We subsidize the production of the same commodity crops that contribute to diet-related disease and provide little support to producers growing more nutrient-rich crops. We spend billions bailing out farmers after major climate-driven droughts or natural disasters, but fail to incentivize climate-friendly farming practices and crop diversification. Our immigration agents raid food processing plants and farms to haul off undocumented workers, yet the same workers are then deemed “essential” and are forced to work under unsafe conditions through the worst of the coronavirus pandemic.

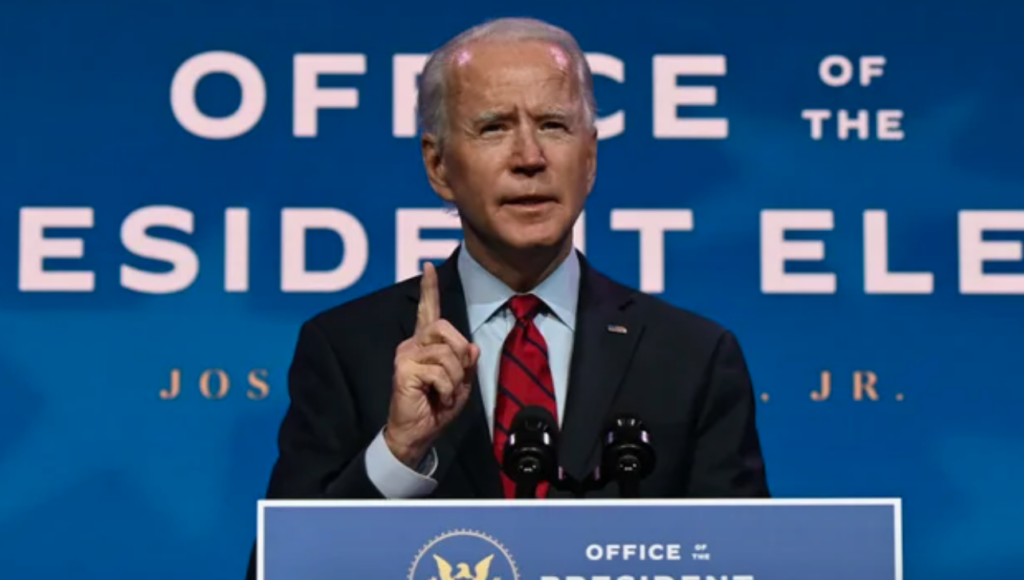

If the incoming Biden administration aims to bring lasting change to public health and the environment, it should start with a transformation of the food system. Fortunately, the tools are in place for a new administration to bring together the relevant agencies and stakeholders to create a national food strategy — a coordinated, strategic approach to food system policy and regulation. Such an approach means engaging the public to identify priorities for the short and long term — from public health to the environment to economic resiliency to racial equity — and harmonizing policies to ensure that the federal food landscape serves that set of goals.

Though a national food strategy has never been a reality in the U.S., the idea has precedent. Three years ago, the Canadian government began public consultations to develop a “Food Policy for Canada” that would work across sectors and all orders of government to “help Canada build a healthier and more sustainable food system.” Similarly, the United Kingdom recently launched a national food strategy that aims to work across government agencies to deliver a low-carbon food system that will simultaneously combat food insecurity and improve public health.

Here in the U.S., the federal government has utilized national strategies to combat other major societal challenges: the 9/11 Commission to work across multiple agencies to identify systemic failures that left our nation vulnerable and to prevent future attacks; the National HIV/AIDS Strategy in 2010, aligning agencies, programs and incentives across various segments of government to guide a collective coordinated response to the epidemic.

The coronavirus pandemic has shown Americans just how fragile our food system is, while exposing countless vulnerabilities and inequalities. These problems won’t go away after the COVID-19 vaccine is deployed, nor will they be solved by the next Farm Bill, by any individual agency regulations, or by any other discrete piece of policy.

The next administration and incoming Congress should work together to develop a comprehensive national food strategy — one that will make our food system healthier and more sustainable, more equitable and economically resilient. We can stop dumping milk and vegetables while children go hungry and be prepared for the next major food system disruption. We can build the food system we need for our society to survive and thrive for generations.

Laurie J. Beyranevand, director of the Center for Agriculture and Food Systems at Vermont Law School, and Emily Broad Leib, clinical professor of law at Harvard Law School Food Law and Policy Clinic, are lead authors of the recently published Urgent Call for a U.S. National Food Strategy.

Filed in: Clinical Voices

Tags: CHLPI, Emily Broad Leib, FLPC, Food Law and Policy Clinic

Contact Office of Clinical and Pro Bono Programs

Website:

hls.harvard.edu/clinics

Email:

clinical@law.harvard.edu