David Satterthwaite Wertime ’07 and Rachel Lu ’07 were walking on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., in 2011 discussing what to do next in their careers when the conversation turned to their common interest in China.

They talked about new microblogging sites that provided Chinese citizens with outlets to express themselves and how so much of what was posted remained unheard in the rest of the world. Wertime and Lu started thinking about how to monitor these sites and explain trends revealed there about Chinese public opinion to a wider audience.

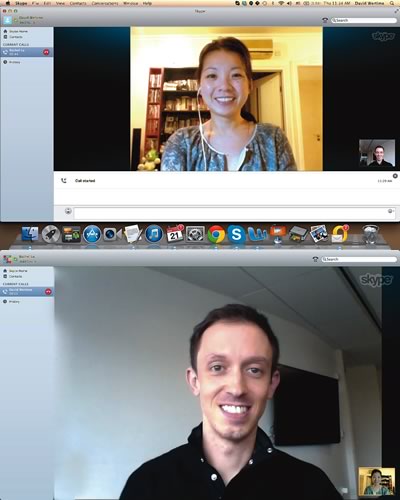

Out of that conversation came Tea Leaf Nation, an English-language online magazine created by Wertime, Lu and her husband, Jimmy Gao ’06. It’s now a destination for Western journalists, academics and decision-makers seeking insights into what average Chinese people are thinking.

Within a year of Tea Leaf Nation’s launch, its articles were already being cited by major news outlets, such as The New Yorker and The Washington Post, and it formed a partnership with The Atlantic’s website and ChinaFile, a project of the Asia Society.

To help fund the site’s growth, Wertime applied for and was among the first recipients of the Harvard Law School Public Service Venture Fund grants, which were announced in June.

In September, Tea Leaf Nation was acquired by Foreign Policy, which plans to feature its content on foreignpolicy.com. Wertime was able to forgo the HLS grant.

Alexa Shabecoff, assistant dean for public service at HLS, said she is thrilled for Wertime and Lu. She also sees it as an important mark of success for the HLS Fund. “What we want to do is find great people with innovative ideas and help them launch,” Shabecoff said.

While neither Wertime nor Lu had prior experience in journalism, both said focusing on China was a natural career progression.

Wertime served as a Peace Corps volunteer teaching English in China after college and worked as a law firm associate in Hong Kong after graduating from Harvard Law School.

Lu was born in Chengdu, China, and, after moving to New York at the age of 12, continued to check out bagfuls of Chinese-language library books and memorized Chinese poetry in her free time.

During law school, Lu spent both summers working in Hong Kong for American firms and wound up working there after graduation, helping China-based companies to access U.S. capital markets.

It was Lu who first came across the microblogging site Weibo, a cross between Twitter and Facebook, when a cousin in China suggested she join to see baby pictures posted by relatives. Lu quickly realized the “enormous” social consequences of Chinese citizens, with few outlets for self-expression, having a platform where they could discuss local or national affairs in real time, unfiltered by state-run media.

Wertime, who also speaks and reads Mandarin, saw Weibo’s potential as a “giant digital public square.”

“People who might not have had other methods of expressing how they felt would say things that were very surprising in their candor,” Wertime said. “That doesn’t mean it wasn’t heavily censored, because it was, and it’s even more heavily censored now, but there was still a lot of rich material to be mined.”

Lu and Wertime, who now work on the site full time, monitor thousands of postings every day on Weibo and other Chinese social media outlets, with the help of approximately 100 contributors who have written stories for Tea Leaf Nation.

The stories range from an analysis of reaction to a new free trade zone in Shanghai to what Chinese viewers think about the American television show “Breaking Bad.”

Skeptical viewers on the comment threads on Chinese video streaming sites questioned how a teacher with a house, pool, and car winds up making drugs, since home ownership and car ownership are badges of wealth in China.

“What Tea Leaf Nation has done is make the Chinese online universe accessible to non-Chinese readers. It serves as an aggregator for people who are interested in a window into China,” said Mark Wu, an assistant professor at Harvard Law School, who began his career as an economist and operations officer for the World Bank in China. Wu reads the e-magazine’s articles for insights into Chinese public opinion.

Tea Leaf Nation’s offerings are attracting readers in mainland China, Hong Kong, and Singapore, as well as the United States, Canada and Western Europe. (Wertime said they don’t reveal traffic numbers but “the growth has been good.”)

“This is one of the sites from which you can try to gather a sense of the pulse of the country,” Wu said.