During a recent lecture at Harvard Law School, civil rights leader Sherrilyn Ifill told her audience that, with the United States embroiled in what she described as a democratic crisis, “we must have the courage to see ourselves as founders and framers of the new America that we are trying to create.” In doing so, she said, we should follow the example of the framers of the 14th Amendment, a group she said that included not only elected officials but also remarkable women and men from all walks of life.

Ifill’s remarks came during a talk she delivered on November 29 titled “Reimagining American Democracy: Becoming Founders & Framers.” The presentation to Harvard Law faculty, students, and staff marked her appointment as the Steven and Maureen Klinsky Visiting Professor of Practice for Leadership and Progress. Ifill used the opportunity to build on remarks she delivered at the 2023 Francis Biddle Memorial Lecture in May and to highlight some of the themes she has shared in class with her Harvard Law students and which she said will inform her upcoming work at the new 14th Amendment Center for Law & Democracy at Howard Law School, for which she will serve as founding director.

The former president and director-counsel of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Ifill began by touching on both the perils she sees facing American democracy and the reasons she remains optimistic. A self-described “unabashed” believer in “the importance of law itself to the health of democracies, as an organizing principle for fairness, justice, and equality,” Ifill acknowledged the vital work of civil rights lawyers of the past.

However, despite their successes over the decades, she said, “part of the crisis we’re in is a law crisis, a crisis in the rule of law, in the legitimacy of law and legal actors, of lawyers and of judges.” To meet that crisis, Ifill argued that lawyers need to “lean in.”

“And in order to lean in,” she said, “we have to have a vision of what we want this democracy to be. My own belief is that we’ve run out of runway on the old vision. It’s not working, or we don’t believe it, or we didn’t create the foundations to make it strong enough.” The new vision for “transformative change” we must further today, Ifill said, is of “a multiracial democracy premised on ideas of equality and justice.” But America’s history of chattel slavery, elimination of native peoples, Jim Crow, and other forms of discrimination, “suggests we are ill suited” to making that vision a reality.

For her, the project of creating a multiracial democracy didn’t start with the writing of the ratification of U.S. Constitution in 1789, but with the end of the American Civil War, a conflict that cost 600,000 lives, including the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln, helped usher in freedom from bondage for millions of Black people, and launched a wave of white supremacist violence in the defeated South. The touchstone for this new American project, was the approval in 1868 of 14th Amendment, she said, “because in its promise, its power, and pragmatism, it is, in my view, the most dynamic and … potentially most powerful provision of our Constitution.”

Backed in Congress by anti-slavery Republicans, the amendment comprised five sections, all designed to enshrine and safeguard the civil rights of the newly emancipated. Section One, “mostly the only part that we all learn in law school,” Ifill said, includes provisions related to birthright citizenship, a topic she would return to later in her talk, as well as the relatively well-known Due Process and Equal Protection clauses.

“Part of the crisis we’re in is a law crisis, a crisis in the rule of law, in the legitimacy of law and legal actors, of lawyers and of judges.”

Section Two, by contrast and despite its importance, “is one that I didn’t learn in law school,” she said. It includes provisions apportioning representation according to “the whole number of persons of each state,” essentially repealing the compromise reached at the Constitutional Convention under which three fifths of a state’s enslaved people were counted in its population. “So just like that,” she said, “we’re talking about transforming a provision of inhumanity to humanity.” Moreover, recognizing likely Southern state resistance to granting African Americans full political rights, Section Two also “set forth a regime of punishment” aimed at states that continued to disenfranchise Black men.

Ifill said that Section Three, which prevents former federal or state office holders who joined an insurrection from holding office again, is “much in the news these days,” in the context of the January 6, 2021 attack on the U.S. Capitol. The amendment’s framers included this provision, she said, “because they understood that this spirit of insurrection was stubborn; it wasn’t something that was likely to simply pass.” With that challenge in mind, Section Five, she explained, “gave Congress the power to enforce the guarantees contained within [the 14th Amendment,] which was their way of saying that we can’t count on the states; it’s going to have to be the federal government that will ensure these rights.”

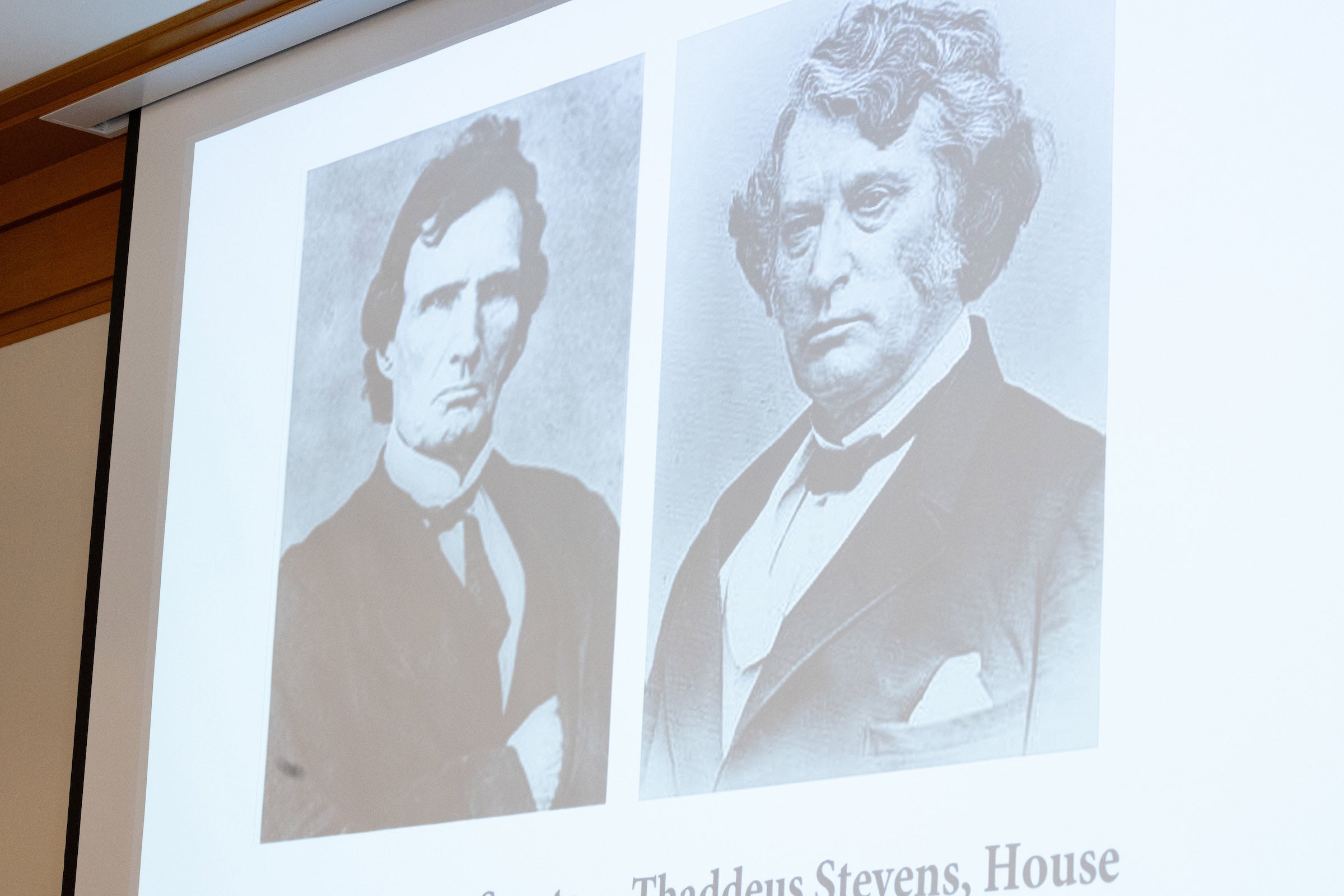

While James Madison, Alexander Hamilton, and Thomas Jefferson often come to mind when thinking about the Constitution’s framers, Ifill said, the mid-19th century legislators who authored the post-Civil War amendments that govern American life today, such as Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts, and Representatives Thaddeus Stevens of Pennsylvania and John Bingham of Ohio, should receive equal billing. “We’re obsessed with the guys in the tricorn hats” but, she argued, that reverence for the founding generation often comes “at the expense of recognizing the Second Founding, and the significance of these individuals.”

“But the premise of the class that I’m teaching now, at the center that I’m creating, and of my own thinking, is that framers and founders are not only those who were elected to office and sat in the legislative chambers,” Ifill said. Paying homage to the groundbreaking work of historians Kate Mansur and Martha Jones (who last year delivered the inaugural Belinda Sutton Distinguished Lecture at Harvard Law School), Ifill said that framers and founders include many people, including free Blacks in the decades before the Civil War, “who helped shape and infuse the words, the concepts, the ideals that were codified in the Civil War amendments and the Reconstruction statutes.”

Drawing from Jones’ work, Ifill argued that these “framers” include people like Gilbert Horton, a free Black man from New York who, working as a sailor, arrived in Washington, D.C. only to be arrested and held in a federal jail under the suspicion he was a runaway enslaved person. When people in New York saw a newspaper advertisement seeking Horton’s presumed owner, they and others rallied to secure his freedom, thereby preventing him from being sold into slavery. As a “cause célèbre,” she said, Horton’s wrongful captivity in the filthy and notoriously harsh D.C. jail. was an embarrassment to Congress and the Lincoln administration.

“Framers and founders are not only those who were elected to office and sat in the legislative chambers.”

Another framer, Ifill said, was Carl Schurz, a Prussian-born Union general whom Lincoln’s successor as president, Andrew Johnson, dispatched to study conditions in southern states. Schurz found that Black people continued to be in danger, that the “spirit of insurrection” persisted, and that “the stubbornness of white supremist ideology was unmoved.” While Johnson, a Southern unionist who “had no problem with slavery,” ignored Schurz’ report, Ifill said it influenced the writing of the 14th Amendment. “When you read this report, you can understand where Section Two and Section Three come from,” she explained.

Women’s suffragists such as Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Stanton should be recognized as founders and framers as well, Ifill argued. They were furious that Section Two of the 14th Amendment protected the voting rights of only “male” citizens, introducing the gender limitation explicitly into the Constitution for the first time. Its inclusion was a politically pragmatic response to the likely backlash against the amendment if it were believed to support the vote for women, Ifill explained. Thus, even though the outcome was not what they wanted, the work of women suffragists helped shape the language and frame the scope of rights articulated in the 14th Amendment. Although it would take women’s suffrage another 50 years, she argued, we should not discount their efforts to raise and sustain the debate about the vote for women after the Civil War.

From the stately photographs of Frederick Douglass to the searing pictures of Black peaceful protesters being assaulted by police in 1965 as they crossed the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama — photographs first seen by those across the nation during breaking news segments on network TV, which interrupted the first televised showing of the powerful film “Judgment at Nuremburg,” Ifill noted the historic and continuing importance of imagery and art to securing the promise of the 14th Amendment. Among the examples she shared with her audience was the iconic 2016 photo of nurse Ieshia Evans confronting police officers in riot gear during a protest against the killing by police of Alton Sterling, an unarmed Black man in Baton Rouge, Louisiana.

“This photograph is what guides my thinking about what a public safety system should be in a democracy in the following way,” Ifill said. “This Black woman is utterly vulnerable. She’s wearing a sheer summer dress. She has no weapons. She doesn’t have a purse. She has a phone.” The police officers, Ifill said, were brought up short by “the sheer courage and determination of this woman.”

“And if I have any role in helping create national legislation around policing, she will have been a powerful framing influence for me, in what I think has to be the relationship between law enforcement and the population,” Ifill continued. “What should bring them up short? What measure of delicacy should be able to be able to disarm law enforcement?”

Art and artists will continue to play a vital role in advancing a renewed vision of a multiracial America, Ifill said. “I truly believe that this project is one that is not just about law and policy, although that is my specialty,” she explained. “I believe that it is also about imagination. … So, I believe that there must be a part of this project that engages artistic expression. What influences our sense of who we are as a democracy.”

To that end, Ifill said that she has begun working with artists and, in addition to teaching at Harvard Law this semester and launching the new center at Howard Law School in 2024, Ifill is participating in a year-long fellowship at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Her hope is to use what she learns to “begin to talk about what are the films, the plays, the art, the dance that might embody a refreshed way of us thinking about who we are and can be as a nation.”

“So that, while we, the lawyers, are working on litigation and bringing the cases and drafting new statutes and thinking about constitutional amendments and thinking about incubating laboratories in courts and in other dispute resolution fora,” Ifill concluded, “we’re tied together with those people for whom imagination is their bread and butter,” in the hopes, Ifill explained “that we will not inhibit ourselves from believing that we too are entitled to imagine what a democracy can be.”

Want to stay up to date with Harvard Law Today? Sign up for our weekly newsletter.