Julián Castro ’00 kicked off his lecture about the future of cities after COVID-19 with a disclaimer and a confession.

It is debatable, said the former mayor of San Antonio and secretary of Housing and Urban Development under President Barack Obama ‘91, whether the country can truly be called post-pandemic when 400 Americans per day continue to die of COVID-19 and 24 million Americans suffer from long-term complications. As COVID stabilizes into an endemic, Castro said, cities will have to learn to “deal with it in smart, thoughtful, and constructive ways.”

Castro’s more upbeat revelation was that he truly loves cities. As HUD secretary, he visited more than 100 of them. So, he was dismayed when headlines published in the early days of the pandemic repeated the conventional wisdom that cities were dying. As the very things that make cities special — public arts and performances, sporting events, and large gatherings — shut down to promote public health, Castro said, it made sense that those who had the option of working remotely would wish to move to more rural areas.

That left cities facing their “toughest years,” he said. Tax revenues dried up, many industries suffered, and cities struggled to provide basic functions. Some also found themselves at war with state legislatures, as state and local authorities vied over mask mandates and other public health measures, said Castro, who was also a 2020 presidential candidate.

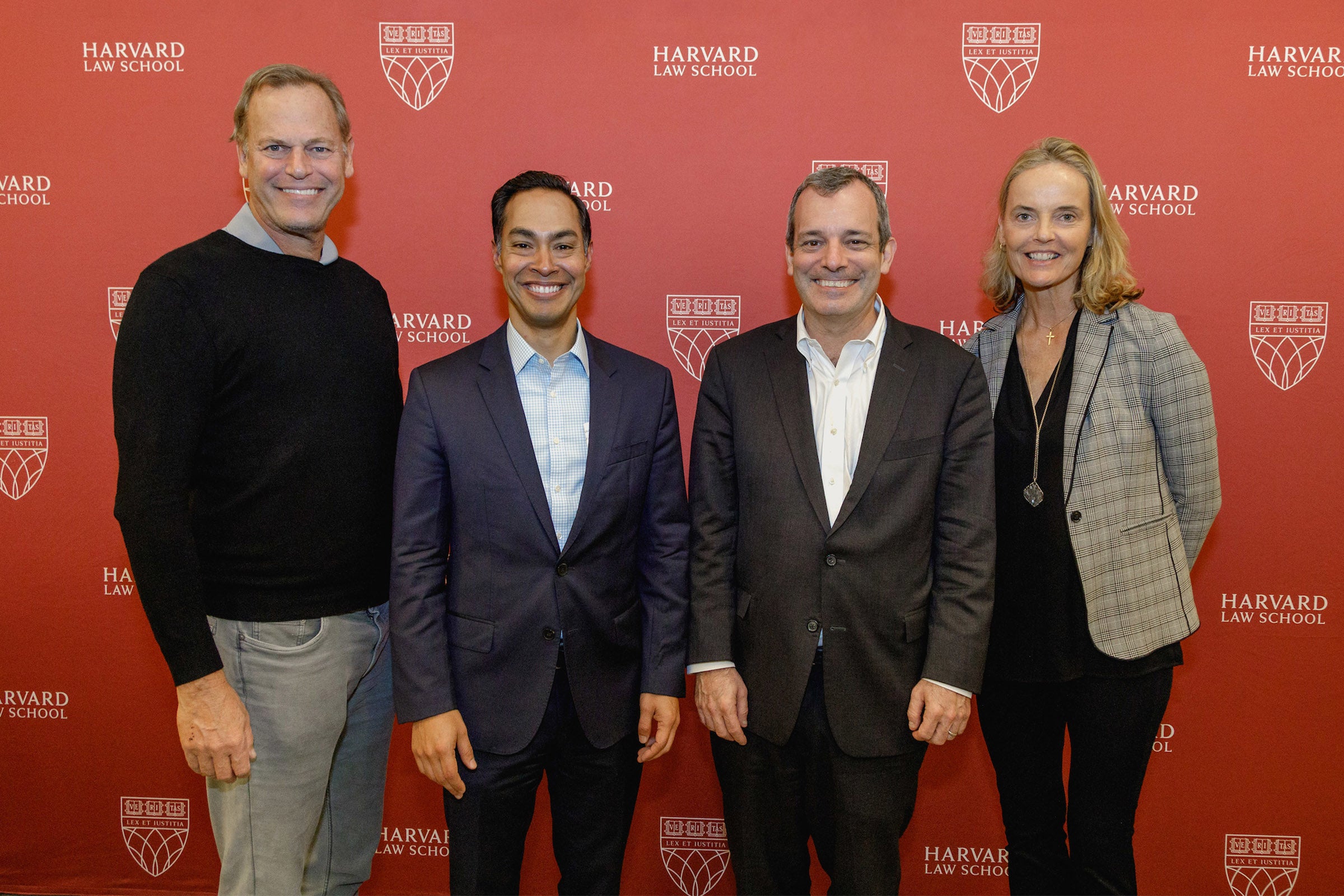

Castro’s remarks, titled “Building Equitable Cities in a Post-Pandemic America,” were delivered on October 26 to mark his appointment as Steven and Maureen Klinsky Visiting Professor of Practice. The position was endowed by Steven Klinsky ’81 and his wife, Maureen Klinsky, to bring to campus leaders from a range of fields beyond law to provide a broad perspective to the law school and university communities.

Two-and-a-half years after the pandemic began, Castro told the Harvard Law School audience, cities are finally bouncing back. And he is convinced that in the years to come, cities can come back stronger and, most importantly, more equitable. Prior to the pandemic, he said, American cities were failing many of its residents. An affordable housing crisis plagues nearly all cities nationwide, poor residents often experience poor public health outcomes, and gaps in access to education persist. These problems all exceed the scope of the pandemic but were exacerbated by it as well, Castro said.

Despite these challenges, Castro described his optimism for the future of cities, particularly in light of unprecedented federal investments coupled with important lessons learned from the pandemic. Castro described cities “the places where things actually get done,” citing their size as a strength that allows residents to get to know and engage with their local leaders and politicians. Cities can “be creative, innovate, [and] not be afraid to go against the grain,” he said.

“Cities are still the places where things actually get done.”

Julián Castro

Castro spoke of experiments cities attempted during the pandemic that could and have led to long-term opportunities for equitable growth and development. In California, Project Roomkey, a program that provided temporary housing in unused hotel and motel rooms for people who are homeless, morphed into Project Homekey, a statewide initiative to purchase dilapidated hotels and convert them into permanent housing with services aimed at vulnerable populations. Denver has successfully implemented sending mental health workers to respond to crisis calls that previously drew a law enforcement response. In many cities, Castro said, temporary conversions of sidewalk space for outdoor dining have prompted local governments to reconsider cutting red tape in other ways so that small businesses can flourish.

One major way for cities to adapt to future needs, Castro said, was to begin to act in the best interests of the greater regions they serve, rather than viewing their cities’ needs as ending at the city borders. Regional economies are simply stronger than city economies, and regional solutions to problems are more likely to be successful than localized ones, Castro said. “The smartest cities are those that can find a way to begin a dialogue and ultimately to act in a regional way on economic development, on affordable housing, and on linking that affordable housing to transit opportunities and job opportunities,” he said.

During his talk, Castro drew on his own political experience. He began preparing for a political career while still a student at Harvard Law School. With his identical twin brother, Joaquin Castro ’00, who currently serves in the U.S. House of Representatives, he laid the groundwork for running in San Antonio’s 2001 city council election during their final year on campus. He won a seat that year, and, in 2009, he successfully ran for mayor of San Antonio, a position he held for three terms. Castro gained national attention in 2012 when he was the first Hispanic person to deliver the keynote address at a Democratic National Convention.

Since its endowment in 2013, the Klinsky Professorship has been held by several honorees, including former FCC Chairman Julius Genachowski ’91; Dr. Eric Lander, president and founding director of the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard; attorney Kenneth Feinberg; former U.S. Representative Jane Harman ’69; entrepreneur, attorney, and activist Chris Kelly ’97; and Mandy DeFilippo ’00, current Harvard Law Lecturer on Law and managing director and global head of risk management for Morgan Stanley’s Fixed Income Division.