If you’re short on time, the history of the first hundred years of Harvard Law School is available as an architectural telegram. On the stone roofline of neoclassical Langdell Hall are engraved the names of those men (yes—all men) who were foundational to the institution’s opening century: Gray, Ames, Thayer, Smith, Story, Greenleaf, Parsons and, of course, Christopher Columbus Langdell himself.

But for a deep, detailed, compellingly written, unstintingly transparent view of the school as it was from the fall of 1817 (six students) to the spring of 1910 (765 students), look to “On the Battlefield of Merit” by HLS Visiting Professor Daniel R. Coquillette ’71 and Bruce A. Kimball, published by Harvard University Press. It is the first of two volumes intended to mark the school’s bicentennial in 2017.

At the core of the book are what the authors call “three radical ideas” developed at HLS that would transform American legal education.

Previous histories of the school come under fire in the new book, including Charles Warren’s 1908 “History of the Harvard Law School and of Early Legal Conditions in America.” Coquillette and Kimball call it a “victory lap” meant to memorialize Harvard’s first place in the realm of legal education, but at the price, they say, of ignoring the stories of racial, ethnic and gender conflict that marked Harvard Law’s first century. (In 1894, for one, Warren, who had graduated from HLS two years earlier, founded something called the Immigration Restriction League.)

With an eye toward full disclosure, “Battlefield” includes HLS’s connection to profits from slavery and its brush with a long-ago era’s mistrust of America’s cultural outliers, including blacks, Irish, Asians, Jews, Italians, and Roman Catholics (a target of explicit institutional vitriol). Evidence of “racism,” most of all, says Coquillette, “runs like a river through volumes 1 and 2.” In addition, there is the exclusion of women from law classes until 1950. (A 1967 history of HLS devotes only three pages to the subject.)

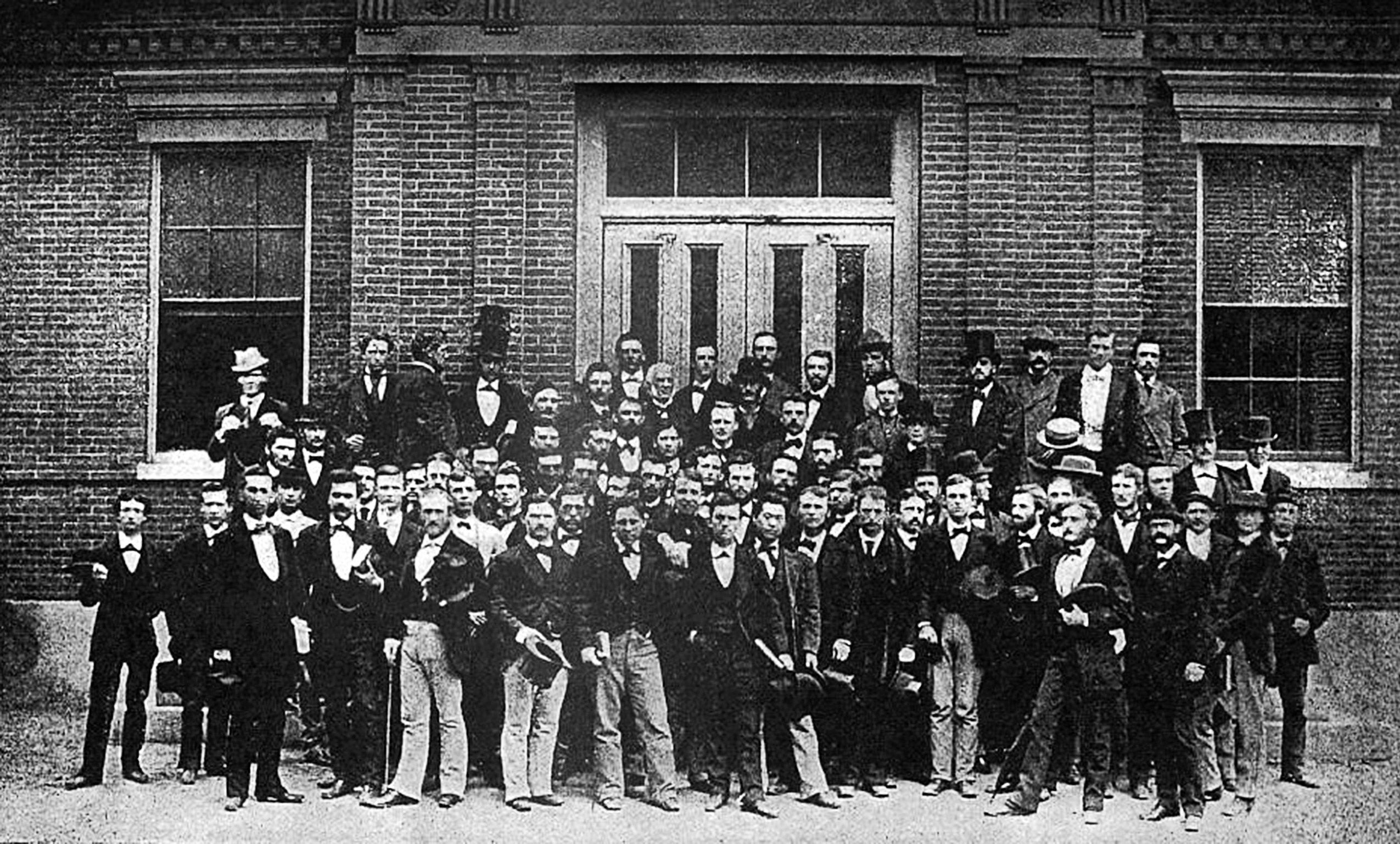

That “Battlefield” will be different is evident at first glance. On the book’s cover is a photo of the Class of 1874, which included the first Asian graduate and the second black graduate, a former slave. The class also arrived in the midst of stunning reforms set in motion between 1870 and 1886. Among them: requiring admitted students to have a bachelor’s degree, or its equivalent; extending the degree track to three years; requiring written examinations; and teaching the law from cases. This inductive method was a pedagogical novelty.

The 1874 picture illustrates another goal of the new history: to take a century-long look at student life. Another chapter describes the novel and uneasy inclusion of students from non-Ivy backgrounds. Most law school histories, says Kimball, “are about what faculty did.”

At the core of the book are what the authors call “three radical ideas” developed at HLS that would transform American legal education.

First, HLS would be a professional school within a degree-granting university, an idea that originated in 1817. (Until the mid-19th century, most lawyers trained as apprentices or at lecture-based proprietary law schools.)

Second, it would defy the notion that all law was local. The idea of a national school came in 1829 with Joseph Story, who rescued a teetering law school and opened the door to an influx of students from the South. Third, attendance at Harvard Law would eventually depend on academic merit, which the authors argue can be traced to Charles W. Eliot’s Harvard presidency, which began in 1869. He conceived of school deans; one of his first hires was Langdell.

The authors also cover another topic that has been excluded from past histories: HLS’s contribution to antebellum legal tangles, and to the Civil War itself. One chapter looks at faculty infighting over the Fugitive Slave Act, the Emancipation Proclamation, the wartime suspension of habeas corpus, and the limits of executive power. Add to that the sheer numbers. On both sides, nearly 600 HLS alumni fought in the war and 111 died, a sum equal to two entire classes in that era. Eleven Confederate generals and 40 colonels went to HLS, as did leaders on the Union side—a total of wartime officers surpassed only by West Point.

“Battlefield” sets itself apart from incomplete histories and from “attack histories,” too, which characterized books on Harvard Law in the late 20th century, including 1994’s “Poisoned Ivy.” Says Coquillette, “We don’t come to this with any ax to grind.”