via IFL Science

by Rachael Funnell

If you caught the recent Oscar-winning film My Octopus Teacher, you’ll likely join octopus enthusiasts in marveling at the incredible intelligence of these complex and curious animals. It may shock you, then, to learn that according to the US federal government, octopuses aren’t considered “animals” when it comes to their treatment in federally funded research. The bizarre legal loophole is recognized by the Animal Welfare Act and National Institute of Health (NIH) and means that octopuses aren’t entitled to the humane treatment afforded to other lab animals. It means that animal welfare organizations have no power to put a stop to reported cases of their mistreatment in federally funded research.

The legal standing seems juxtaposed to the cognitive and behavioral traits of octopuses, which have seen them become increasingly frequent test subjects in federally funded research in recent years, says a release from Harvard Law School. Despite being animals, the status applies to all of the cephalopods, many of which (such as cuttlefish) appear to have cognitive capabilities sufficient to understand suffering. A recent study (not federally funded) found they understand pain, as well as feeling it, and organizations have campaigned against octopus farming which they say is not fit for purpose considering the intelligence and short lifespan of these animals.

“Under existing law, cephalopods are not required to be provided with “the appropriate use of tranquilisers, analgesics, anesthetics, paralytics and euthanasia” or “appropriate pre-surgical and post-surgical veterinary medical and nursing care,” wrote clinical fellow Kate Barnekow of the Animal Law & Policy Program at Harvard Law School in an email to IFLScience. “This means that cephalopods may be used in studies deemed inhumane to conduct on other animals – or too expensive to conduct on other animals that would legally be required to be provided with appropriate sedatives, pain-relievers, and surgical care.”

Because cephalopods are not considered “animals” under the current regulatory scheme, there is no way to accurately tell how many are being used in research, explained Barnekow, but published research and a recent spike in memberships to the Cephalopod International Advisory Council appears to indicate that the number is increasing. The exact nature of the research in question is of course relevant when looking at published studies, as not all of them are federally funded, but without a standardized system for implementing quality care control, it remains legal and undetectable to treat cephalopods inhumanely in certain contexts.

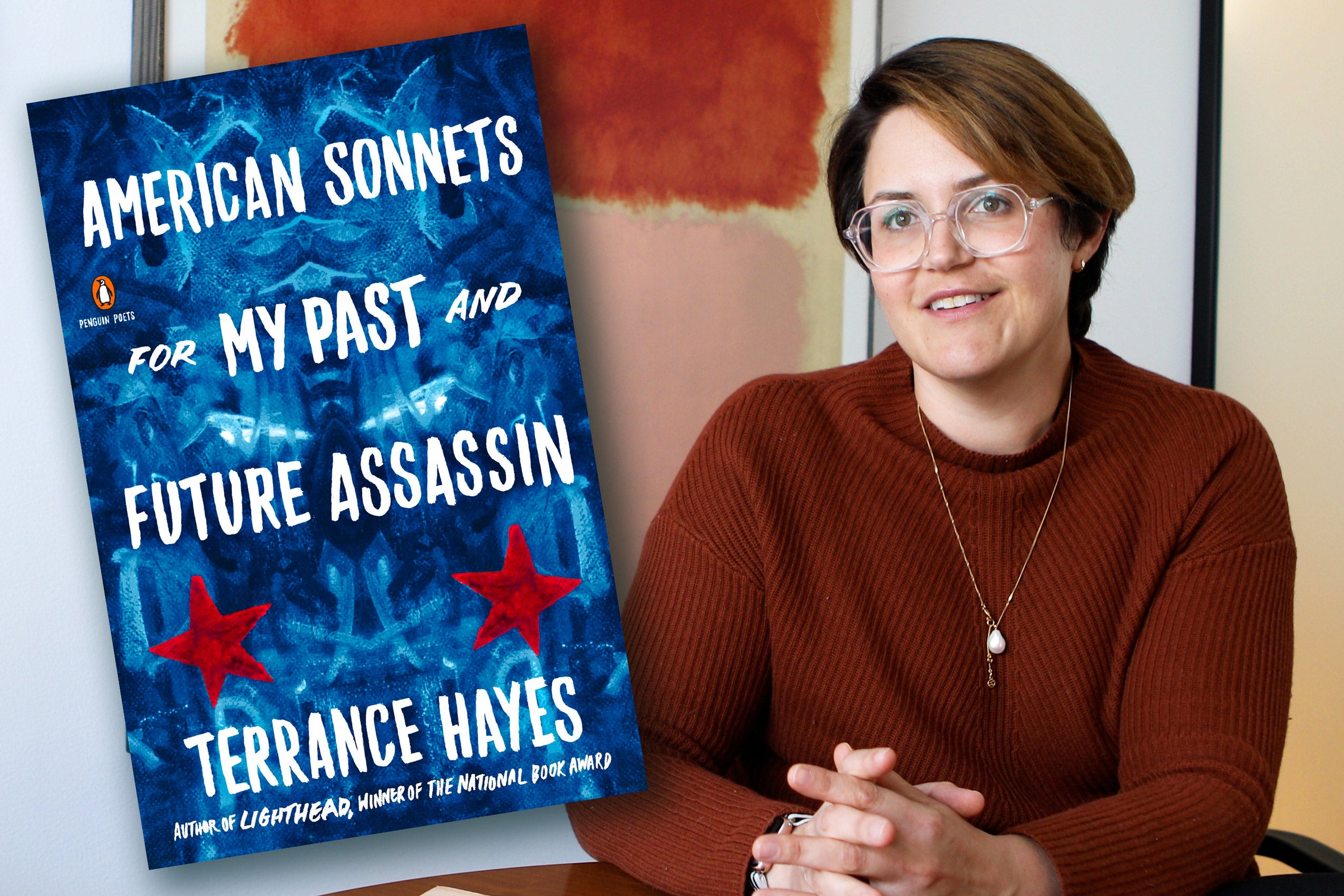

In December 2020, the Animal Law & Policy Clinic submitted additional exhibits in support of a petition put to the National Institute of Health to revise the existing legislation surrounding the use of cephalopods in research. This included the film My Octopus Teacher, one of the scientific advisors of which was a signatory of the Petition which you can read here.

Filed in: Legal & Policy Work

Tags: Animal Law & Policy Clinic, Animal Law and Policy Clinic, Kate Barnekow

Contact Office of Clinical and Pro Bono Programs

Website:

hls.harvard.edu/clinics

Email:

clinical@law.harvard.edu