The way John Kroger ’96 tells it, getting caught trying to steal three hubcaps a few weeks before graduating from high school in Texas was the luckiest thing that could have happened to him.

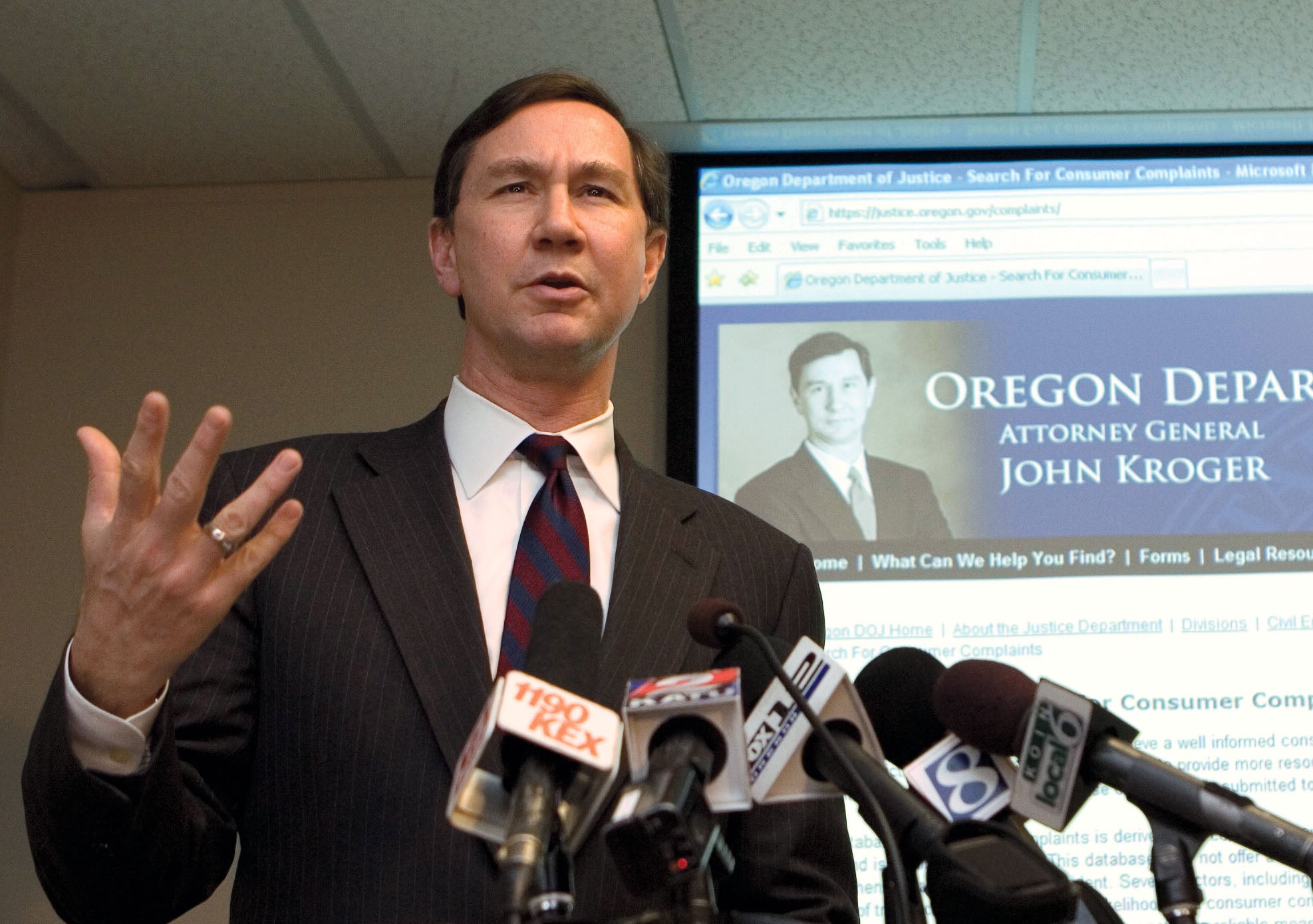

It is perhaps an odd admission for someone who went on to become a federal prosecutor and is now Oregon’s attorney general.

But getting caught—and kicked out of his parents’ house—is what prompted Kroger to enlist in the Marines, an experience he credits with instilling in him a desire to work in public service.

“Everything that has happened in my life since that time is directly related to those three years in the Marines,” Kroger said. “Every single day, they tell you your country is worth giving up your life for. You live through that and internalize it.”

Kroger went from being a Marine reconnaissance scout to a Yale undergraduate to an aide for then-Rep. Charles Schumer ’74 and then for Bill Clinton’s presidential campaign, before he enrolled at Harvard Law School. After clerking for a year, he landed a job in 1997 as an assistant U.S. attorney in the Eastern District of New York, where he quickly racked up a list of high-profile convictions against drug dealers and mobsters.

But after he nearly burnt out on the job, Kroger set out on a three-month cross-country bike ride in 2000, during which he fell in love with his final destination: Portland, Ore.

Two years later, he returned there as a professor at Lewis & Clark Law School. Kroger taught only a single semester before he was drafted into joining the Justice Department team prosecuting top Enron executives.

His experiences as a prosecutor provided plenty of fodder for his 2008 book, “Convictions,” in which he recounts all of his big cases and the colorful rogues he encountered along the way as well as the unease he felt about what he was doing.

Kroger admitted he was bothered by the pressure and manipulation he applied during interrogations, which he came to view as doing “moral damage” to both interrogator and subject. He also questioned the wisdom of the war on drugs, which he concluded overemphasizes interdiction and enforcement at the expense of treatment.

The book won Kroger praise for its honest portrayal of what it’s like to be a federal prosecutor. It also provided ammunition to his opponents later that year, when he decided to run for attorney general. As a first-time candidate and relative unknown in his adopted state, he had to learn how to raise money and master the art of retail politics.

“I don’t look like Robert Redford, and I’m very cerebral and actually pretty introverted,” Kroger said.

Nevertheless, he managed to beat the Establishment candidate in a tough Democratic primary battle, thanks to a coalition of unions, environmental activists and the law enforcement community. He wound up the Republican write-in candidate too when the GOP didn’t field its own nominee.

Since taking office in 2009, Kroger has raised the profile of the attorney general’s office, which traditionally served as a behind-the-scenes adviser to state government agencies, said Norman R. Williams, director of Willamette University College of Law’s Center for Law and Government.

Kroger has aggressively pursued consumer fraud cases and made environmental protection and drug treatment his other top priorities.

“By and large, he’s done a good job of presenting himself as an activist attorney general,” said William Lunch, an Oregon State University political science professor and Oregon Public Broadcasting political analyst.

But Kroger’s efforts early on to shake up his department, which also oversees the state’s children’s support services, didn’t sit well with all 1,300 employees.

“Change is very hard for people,” said Kroger, who said his goal is to make his office the “best in the country.” He added, “We have a ways to go.”

Kroger said he is “very likely” to run for re-election in 2012 but won’t make any decision until later this year.

His prodigious fundraising and frequent travel around the state have political watchers there convinced he’s set his sights on a higher office, such as U.S. senator or governor, positions occupied by fellow Democrats for the foreseeable future.

But in March, fresh off his second argument this term before the U.S. Supreme Court, Kroger sounded content, at least for now.

“I’d be very ambivalent running for a different office where you’re a politician first and not really a lawyer,” he said. “I love doing both.”