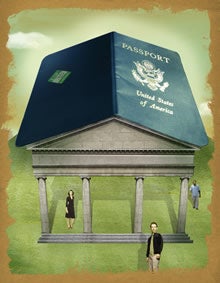

The new curriculum embraces law’s increasingly transnational nature

Should the Geneva Conventions apply at Guantánamo Bay?

Should American courts look at the laws of other countries when interpreting the U.S. Constitution?

What can be learned from cultures and countries that approach law differently from the way we do?

Questions like these will be mandatory for first-year students at Harvard Law School, thanks to a new set of international legal studies courses that is now part of the school’s required first-year curriculum.

“We concluded that no student should graduate from law school without exposure to law beyond the United States, whether international or comparative,” said Dean Elena Kagan ’86. “This requirement should take place in the first year,” she added. “While students are building their conceptual map of the law universe, they should locate U.S. law in an international context.”

The mandatory inclusion of international legal studies early in the school’s academic program reflects the increasingly global nature of legal practice, and the growing international sophistication of the students themselves, says Professor Martha Minow, who chaired the curricular reform efforts. Many students are entering law school with backgrounds in international studies or with overseas experiences, or are going abroad for their summer jobs while enrolled in law school. “The reforms are finally catching up to where our students are,” said Minow. The creation of new courses, together with the law school’s plans to continue building on its strength in international and comparative legal studies, has occurred in tandem with the recent hiring of a number of new faculty members.

To meet the new requirement, students will choose one from among five courses, starting the second semester of the first year. Each of the first-year courses is meant to be foundational, preparing students for more advanced courses available in their second and third years. The courses are Public International Law, sections of which will be taught by Assistant Professor Gabriella Blum LL.M. ’01 S.J.D. ’03 and Visiting Professor Curtis A. Bradley ’88; Law and the International Economy, sections of which will be taught by Assistant Professor Rachel Brewster and Professor Jack L. Goldsmith; The Constitution and the International Order, taught by Professor Noah Feldman; and two comparative law courses—one taught by Professor William P. Alford ’77, the vice dean for international legal studies, focusing on China, and the other taught by Professor Duncan Kennedy, focusing on the development of private law systems and doctrines around the world.

As this roster of courses suggests, rather than introduce students to the discipline through a general survey course—“What would it be a survey of?” Kennedy wonders—the law school opted to require students to take one of several courses exploring an aspect of international legal studies. Once conceived solely as the legal relationships between nations, “international law” is now generally understood to encompass much more than that, Blum notes, including private business relationships, and relationships between individuals and among family members; the international regulation of transactions, criminal activities, human rights and environmental impacts; labor; and immigration—in short, the entire range of human endeavor. “It doesn’t make sense to survey all dimensions,” Kennedy said. “It would be so general as to be almost useless.”

Regardless of which course they take, students will be introduced to the amalgam of systems, instruments, institutions, agencies and documents that inform international law today, says Blum. Adds Feldman, they will grapple with these elements through case studies pulled from headlines, and explore perspectives by arguing from the viewpoints of judges, presidents, legislatures, international tribunals and other international actors. The idea, says Alford, is to show national and international institutions in all their complexity, to explore law and custom and how they relate, to place international legal forces in social, economic, historical, and political contexts, to consider how law moves from one society to another, and to see how law takes shape in other societies. The particular subject of each course will provide the lens through which students can focus on these themes.

Alford, for instance, will ask his students to consider the role that formal and informal legal institutions have (or haven’t) played throughout China’s long and varied history. Looking at China’s efforts over the past 30 years to build a legal system, the course will consider “what may or may not be fundamental and universal in legal order,” he said. And throughout, he promised, he will “endeavor to link what students are learning to their other first-year courses.”

No casebooks exist for these courses; faculty members have been putting together their syllabi from scratch. “When teaching a course for the first time, you try to select materials that will make the conversation rich and exciting, but you don’t know if they’ll fly,” said Feldman. “There’s an element of improvisation when there is no set of prescribed materials to use. It’s more like jazz than classical music.”

The new first-year international legal studies requirement is one piece of a growing international emphasis across the broader HLS curriculum. Professors in courses more focused on the U.S. have introduced elements of comparative law to sharpen students’ understanding of U.S. law and to raise their awareness of the ways different societies address similar issues. In addition, the roster of courses focusing on international and comparative law has expanded dramatically: 2Ls and 3Ls will be able to choose from more than 70 of these courses next year. Alford notes that HLS professors are engaging more and more with foreign scholars in teaching and research, and foreign students in the graduate program bring valuable non-U.S.-centric perspectives to class discussions. Students also have a variety of opportunities to spend a semester overseas for credit (see story), participate in international projects and programs, and even pursue a joint degree in the U.K. at the University of Cambridge.

The law school’s emphasis on international and comparative legal studies bodes well for the ability of its future alumni to influence this nascent and burgeoning field of law, says Brewster. “A lot of things are being formed now,” she said. “These are areas where the institutions are in flux. Our students want to embrace that. They want to be part of the generation coming up with innovative answers.”