In the 1970s, many went into law to make a difference. Some of them are finally making it now. Today’s young lawyers don’t want to wait that long.

Thirty years ago, after Vietnam and Watergate, young idealists entered the legal profession in unprecedented numbers, choosing law as their way to “be the change,” as Mahatma Gandhi urged. Some became Nader’s Raiders, some went into government and a few managed to find jobs in places like Appalachia or the inner cities. Many, however—discouraged by low pay or scarce opportunities—took other paths.

But today, as the 1970s generation reaches its 50s and 60s, growing ranks of lawyers are pursuing “second acts” in public service and pro bono, after years of doing entirely different work. The trend is one of several which, taken together, hint at the coming areas of growth in public interest law.

Another is the emergence of young lawyers who are building viable solo practices in underserved areas. And, in some large law firms, where pro bono work hasn’t always been supported to the extent that it could be, there are new initiatives to facilitate it. Even critics cautiously acknowledge the stepped-up activity in firms, hopeful that more sustained commitment will follow.

There are also growing numbers of “cause lawyers” supported by well-funded organizations across the political spectrum, and new “hybrid” firms that do some paid work in order to subsidize their predominantly pro bono caseloads. Together, these developments show that the options for public-spirited work are taking new forms.

Second acts at home and abroad

- Credit: David Deal Tony Essaye ’61 stared at retirement and didn’t like what he saw. Today, in the second act of his career, he’s looking to make a difference.

Six years ago, Tony Essaye ’61, then a partner at Clifford Chance, and his good friend Bob Kapp, a partner at Hogan & Hartson, had the ugly “R” word on their minds: retirement. But neither was inclined to take that option. Why not put their combined years of accumulated experience to good use, by sharing their knowledge with those who might not have access to legal services? And why not find other like-minded lawyers nearing retirement to join them?

Kapp had a long-standing interest in international human rights, and Essaye had much experience in international business. It made sense that their inclination was to go global. Buoyed by enthusiastic interest from lawyers at home and organizations abroad, they launched the International Senior Lawyers Project.

ISLP engages experienced lawyers—some retired and some in active practice—to volunteer for legal projects in or affecting developing nations. The projects take place in many regions—southern Africa, Eastern Europe and India, to name a few—and their common goal is ambitious: to promote the rule of law by furthering human rights, increasing access to justice and promoting equitable economic development.

They began by assisting organizations like Ashoka, an Arlington, Va.-based nonprofit that provides fellowships to social entrepreneurs, particularly in developing countries. In one project, they helped the Human Rights Law Network—India’s largest public interest law firm—push for broader rights and protections that are relatively new in India. “We’ve worked with them on issues like disability, domestic violence, sexual harassment and discrimination on the basis of caste,” Essaye said. Volunteer lawyers have spent considerable time helping integrate U.S. precedents in these areas into the Human Rights Law Network’s litigation strategies.

ISLP also works with the Open Society Justice Initiative, which combats corruption, promotes freedom of information and increases access to justice in various former Soviet Bloc countries. According to Essaye, in many of these countries, legal assistance had been theoretically guaranteed to those who cannot afford it since the Communist era, but the system had completely broken down. Now governments are open to change, including new programs modeled on the public defender system in the United States, and ISLP has been sending experienced attorneys to assist in this process.

In June 2004, ISLP launched a venture with the Black Lawyers Association of South Africa, setting up a 10-week pilot program of practical “hands-on” instruction in commercial law for some 30 black attorneys in Johannesburg, conducted by experienced American commercial lawyers. During apartheid, black attorneys were effectively precluded from practicing business law, with the result that, today, many younger black attorneys lack the mentors and other support systems that would normally facilitate lawyers’ pursuit of a commercial law practice. The program has since been expanded to include sessions in Durban and Cape Town.

“Our goal is to make this not only a teaching program,” said Essaye, “but a program that will help black attorneys increase their contribution to the South African economy and society.”

Expanded pro bono opportunities in law firms

The Washington, D.C., office of Hogan & Hartson might seem an unlikely place from which to accomplish the construction of a major new infrastructure project for post-genocide Rwanda. But Claudette Christian ’79, a partner in the firm, is doing just that. Under the auspices of the ISLP, Christian is working pro bono with a team of lawyers and the Rwandan government to develop a power plant that will use methane gas extracted from Lake Kivu as its power source. Electricity generated by the plant will then be fed into the existing grid. For Rwanda, where hopes for recovery and stability lie in the reduction of staggering poverty, the project is critically important.

Christian practices principally in the areas of international corporate and finance work to develop projects in the oil and gas, telecommunications, transportation and aviation industries in emerging markets. Joe Bell, an ISLP board member and a senior partner at Hogan & Hartson, believed she was an ideal choice to head up a team of project finance lawyers, and invited her to take the reins and spend as much time as she needed to accomplish the financing.

Her work for ISLP and Rwanda is an example of new, more flexible accommodations of pro bono practice in some law firms. More firms are dedicating full-time slots for pro bono lawyers. Some are now even allowing equity partners to practice full time for pro bono clients. While many observers say that firms could be doing much more, there has nonetheless been a spike in law firm encouragement of pro bono work, says Esther Lardent, president and CEO of the Pro Bono Institute at Georgetown University Law Center, an organization that offers research, analysis, technical assistance and training on innovative approaches to enhance access to justice for the poor and disadvantaged.

One catalyst has been the American Bar Association’s ongoing challenge to firms to devote 3 to 5 percent of their total billable hours to pro bono work, says Harvard Law School Professor David Wilkins ’80. Furthermore, he notes, many firms are motivated by hopes of making The American Lawyer magazine’s “A list,” a ranking of the top 20 law firms based on their commitment to associate satisfaction, revenue per lawyer, diversity—and pro bono work.

“In the war for talent,” Wilkins said, “and in order to keep the lawyers in the law firms, they want to make the law firms places where people can do meaningful work.”

Several major firms have hired full-time directors to oversee their pro bono commitments. Daniel Greenberg, former president and attorney-in-charge of the Legal Aid Society, for example, was hired to be director of pro bono at Schulte Roth & Zabel, the firm that the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law recently chose to serve as co-counsel representing victims of Hurricane Katrina in a class-action suit against FEMA. Greenberg was director of clinical programs at HLS from 1987 until 1995.

Some observers point out that law firm pro bono contributions are just a drop in the bucket compared with what they are earning, and are still falling well short of where they should be. Cameron Stracher ’87, a professor at New York Law School and the author of “Double Billing,” a nonfiction account of life as a law firm associate, said that while any effort to encourage more pro bono is commendable, the new emphasis on pro bono is “just a bright and shiny lie that big firms use to lure law school graduates.”

But Mark O’Brien, founder of Probono.net, an online network of public interest lawyers, said that if the question is whether law firms are doing more good than in the past, “the answer is, clearly, yes.”

One model program is that of Holland & Knight, whose Community Service Team includes 10 lawyers. Five are fellowship recipients with two-year appointments to work pro bono full time, and five are senior lawyers who stay in the positions permanently. Two to three associates who join the firm each year are fellowship recipients and are paid the same salary as other Holland & Knight associates at the same level (the starting salary was raised to $145,000 in their New York office this year).

Credit: Andrea Artz Harmony Loube ’04 had every reason to choose a high-paying job instead of public interest work. She found a way to have both.

Harmony Loube ’04 had every reason to choose a high-paying job instead of public interest work. She found a way to have both.

Harmony Loube ’04, a Chesterfield Smith Fellow in Holland & Knight’s New York City office, wanted to pursue public interest work after clerking for a federal judge. But, as the oldest of seven siblings (“I always have a couple of brothers living with me,” she said) and as the daughter of a beloved mother whom she would love to rescue from Section 8 housing in Maryland—and as a mother of a 6-year-old son herself—Loube felt her prospects for doing public interest work were limited by her financial considerations.

“Harvard was a big blessing for me,” she said. “And from that blessing came a sense of responsibility to help my mother and my brothers.” But, at the same time, Loube could not turn her back on a need to do some good in the larger world, to use her law degree to address the wrongs she feels riddle the criminal justice system. Her mother, she says, despite her own financial situation, counseled her to follow her heart. “She could tell how passionately I felt about working in criminal defense,” Loube said. “I felt a responsibility to represent people that I had seen all of my life locked out of the justice system simply because they could not afford adequate representation. But I didn’t know how I could do public interest work and not make money, not help out my family.”

When a staff member in HLS’s Bernard Koteen Office of Public Interest Advising told Loube about the relatively new Chesterfield Smith Fellowship, Loube jumped at the opportunity. The fellowship enables her to do the work she loves and earn a Holland & Knight salary.

“It’s a win-win for our clients,” she said. “They have people completely dedicated to them who are making the same salaries as the other lawyers doing billable work. Our pro bono clients are our priority. It’s not like we’re saying, first we have to take care of the billable work. And it’s a win for us because we get to stay on at the firm after having an amazing amount of responsibility.”

After two years of 80 percent pro bono and 20 percent billable work, Loube will become a regular associate. Once Smith Fellows make that transition, she says, they are still expected to do pro bono work, an expectation that she is very pleased with. She also says the transition will be made easier by the 20 percent billable work she has done, which has allowed her to form both mentoring and business relationships throughout the firm. “It’s very important for a minority lawyer to get that sense of support.”

Solo practices in underserved communities

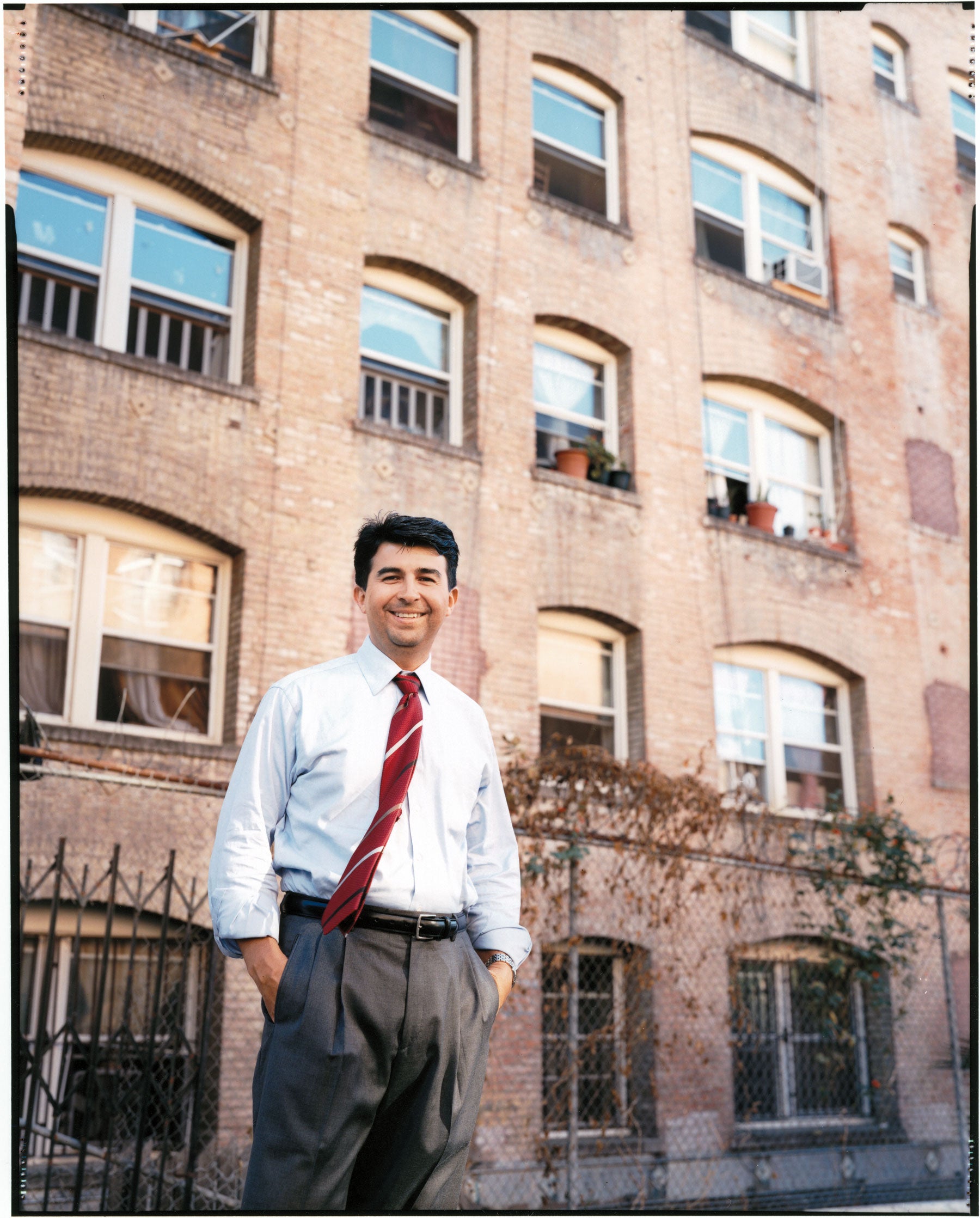

Credit: Amanda Friedman Eric Castelblanco ’91 was defending a products liability case when he realized he would prefer to represent victims in the Los Angeles area, where he grew up.

Luz Herrera ’99 and Eric Castelblanco ’91 graduated from law school with the same intention: join a prestigious law firm, pursue a worthwhile career, work hard and make a good living. But both found some things missing in that formula: giving back to the communities of Los Angeles where they grew up, and working directly with their clients.

Herrera opened a solo practice in Compton, Calif., four years ago, and Castelblanco began a solo practice in Beverly Hills in 1995, serving clients who live in the underserved communities of Los Angeles. Both attorneys, bilingual in English and Spanish, feel that providing affordable legal services to a community is worth more than a fat paycheck. But neither imagined such a career path while in law school.

“I always saw myself in a boardroom, not a courtroom,” said Castelblanco, whose parents emigrated from Colombia when he was 2. “The turning point came during a meeting when I was defending a products liability case. I was across the table from the lawyer representing the man who had been injured in the case. And I realized that I wanted to be that lawyer.”

Herrera began her career as an associate in the real estate department of a large San Francisco-based law firm. But she found herself working under a partner whose attitude was “If I have to explain, what is the point? I might as well do it myself.” She left after two years, worked for a year as a contract attorney and provided consulting services for several organizations.

In May 2002 she opened The Law Office of Luz E. Herrera in Compton—only blocks away from the site of the 1992 Los Angeles riots. It was an unorthodox choice, with huge challenges—“heartache and depression,” she said—but ultimately one that has rewarded her with a successful practice and satisfied clients who are relieved to find a lawyer who speaks Spanish and can help them navigate the legal system. The mission statement on her Web site offers clients “affordable legal services in the areas of family law, estate planning, real estate and business transactions … in the most cooperative, cost-effective and healthy manner.”

When Castelblanco began his solo law practice, he mainly focused on using his fluency in Spanish to help clients with immigration matters. But in 2000, when one of his clients came to the office in tears, describing intolerable living conditions at her apartment in a large Los Angeles housing complex, he shifted his focus to representing tenants living in substandard housing. “I had a gut feeling that this could be a case,” he said, after visiting the client’s roach- and rodent-infested apartment, and he asked if other tenants would join a lawsuit. Ninety-three other people (about half the tenants) decided to do so. The result of Martha Alvarado et al. v. RMR Properties was a $2.14 million settlement, which enabled 15 families to put down payments on their own houses.

For both Castelblanco and Herrera, there was no road map for an Ivy-educated lawyer to start a viable law practice for low-income clients. “Traditionally, if you want to do public service, you are directed to apply for a Skadden fellowship, work for the government or go to a civil rights impact litigation organization,” said Herrera. “But for me, none of those options seemed like the right choice. I did not want to spend 90 percent of my time doing research or working in a direct-service organization whose approach I did not completely buy into. Working in my own law office allows me to provide legal services to individuals who may not otherwise have an attorney and tap into my entrepreneurial spirit while being an active member of the community.”

But before Herrera could help people navigate the legal system, she had to figure out the nuts and bolts of running a law practice, including how to set up a billing system—problems that a first-year associate at a major firm would never have to worry about. “The first year is very hard,” she said. “No one tells you how to set up a practice in law school.”

To ease the path for those inclined to pursue similar practices, Herrera founded Community Lawyers Inc., a nonprofit organization that aims to provide mentorship, training and support to young lawyers who are interested in providing legal assistance to traditionally underserved communities.

She took a break from her practice to return to Harvard in May, joining the Community Enterprise Project at the Hale and Dorr Legal Services Center as a senior clinical fellow and instructor. One of the programs she has conceptualized is a two-year fellowship that would help law graduates learn how to start law practices in underserved communities.

Credit: Asia Kepka Luz Herrera ’99, outside HLS’s Hale and Dorr Legal Services Center, where she’s an instructor and senior clinical fellow this year.

Herrera hopes that her research at HLS will help Community Lawyers Inc. introduce models for delivering affordable legal services that are sustainable in different communities. But she is careful to point out that she believes that a lawyer in solo practice should be able to make a decent living—an idea with which Castelblanco, married with three children, heartily agrees.

“The sense that I am getting from law students and young attorneys is that if they could be guaranteed a minimum salary for the first two years of at least $35,000, they would be interested,” said Herrera. That’s why the focus of her research has been on bringing together concepts that often seem miles apart: personal fulfillment and economic sustainability for the lawyer, and filling the gap in legal services for working and middle-class Americans. Law school graduates are too often forced to choose one or the other, says Herrera. She believes lawyers can, and should, have both.

Herrera is hopeful that she and Castelblanco are at the forefront of a sea change in law culture, a change that would promote community-based practices by encouraging bright young attorneys to bring top-drawer legal education—paired with a set of practical skills—back to the communities that need them. However, even if lawyers in private practice in underserved communities could be guaranteed enough money, Herrera still sees potential pitfalls without a mentoring program in place.

“If there isn’t a model for lawyers to do what I did—if there isn’t a blueprint—then it ends with us,” she said.