It is the rare law review article that directly leads the Supreme Court to change how it does business.

But that’s exactly what happened after the Harvard Law Review published an article in 2014 by Harvard Law Professor Richard Lazarus ’79, revealing how Supreme Court opinions get changed after issuance, with little public notice.

At the start of the new term last October, the Court announced that any future changes will now be noted on the Supreme Court’s website.

That policy change is just the latest example of the wide influence of Lazarus’ scholarship, which, in recent years, has also included a groundbreaking study of how an elite bar has come to dominate practice before the Supreme Court.

“Not many people had written about advocacy before the Court—and advocacy within the Court—from a scholarly perspective,” said Lazarus. “It came naturally to me, not just to understand the Court’s work by reading the opinion itself, but [to try] to understand what forces led to that opinion and what the Court did and didn’t do.”

Lazarus, who joined the Harvard Law School faculty in 2011 from Georgetown University Law Center, has long divided his attention between the Court’s inner workings and his other specialty, environmental and natural resources law. He served as executive director of the national commission that examined the BP Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill, and he was the principal author of the commission’s 2011 report.

Lazarus said his interest in how the Court operates dates back to his “formative time” in the solicitor general’s office, where he worked between 1986 and 1989 and argued nine times before the Court (he has since argued there four more times).

It was during his time as an assistant to the solicitor general that Lazarus had his first exposure to the Supreme Court’s informal procedures for updating already-published opinions. His client, the Environmental Protection Agency, wasn’t happy with seemingly extraneous language in an opinion in a Clean Water Act case.

“It’s a testament to … the nuance of Richard’s work that a Supreme Court justice could read it and learn something new about how the Court functions.”

Lazarus thought such adjustments weren’t possible, but a veteran deputy solicitor general told him all he had to do was write a letter to the reporter of decisions explaining why language could be changed. “I said, ‘You’ve got to be kidding,’ but I did it and they made the change. When that happened in 1987, I said, ‘I’m going to write about that someday.’”

That day finally came in 2011, when Lazarus began what he described as “scorched-earth” research, which included combing through the papers of half a dozen justices at the Library of Congress and utilizing computer programs to scan more than a century of Court opinions.

What he discovered was that the justices revised their opinions “in significant, including highly substantive, ways” and that not all methods employed for making such revisions were particularly transparent. At the end of his article, Lazarus recommended the Court follow the lead of what Congress and federal agencies do in revising legislation or correcting errors in regulations—by providing after-the-fact public notice.

Lazarus’ findings made headlines, starting in The New York Times, where Supreme Court reporter Adam Liptak noted the justices were “quietly revising” their decisions and “altering the law of the land without public notice.”

Soon after Lazarus’ article was published, Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg ’56-’58 and Elena Kagan ’86 began giving out notices when they made changes. As of the start of the October 2015 term, it became policy Court-wide. Other courts, including the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court and the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 1st Circuit, have adopted similar procedures, Lazarus said.

“It’s very gratifying,” he said. “I would rather write an article that solves global climate change, but this one was certainly a lot of fun.”

An earlier law review article Lazarus wrote on the impact of the elite Supreme Court bar dominated by a handful of corporate law firms has also had broad resonance. In that 2008 Georgetown Law Journal article, he showed how the justices are more likely to grant cert. petitions filed by members of the expert bar, who also prevail more frequently on the merits.

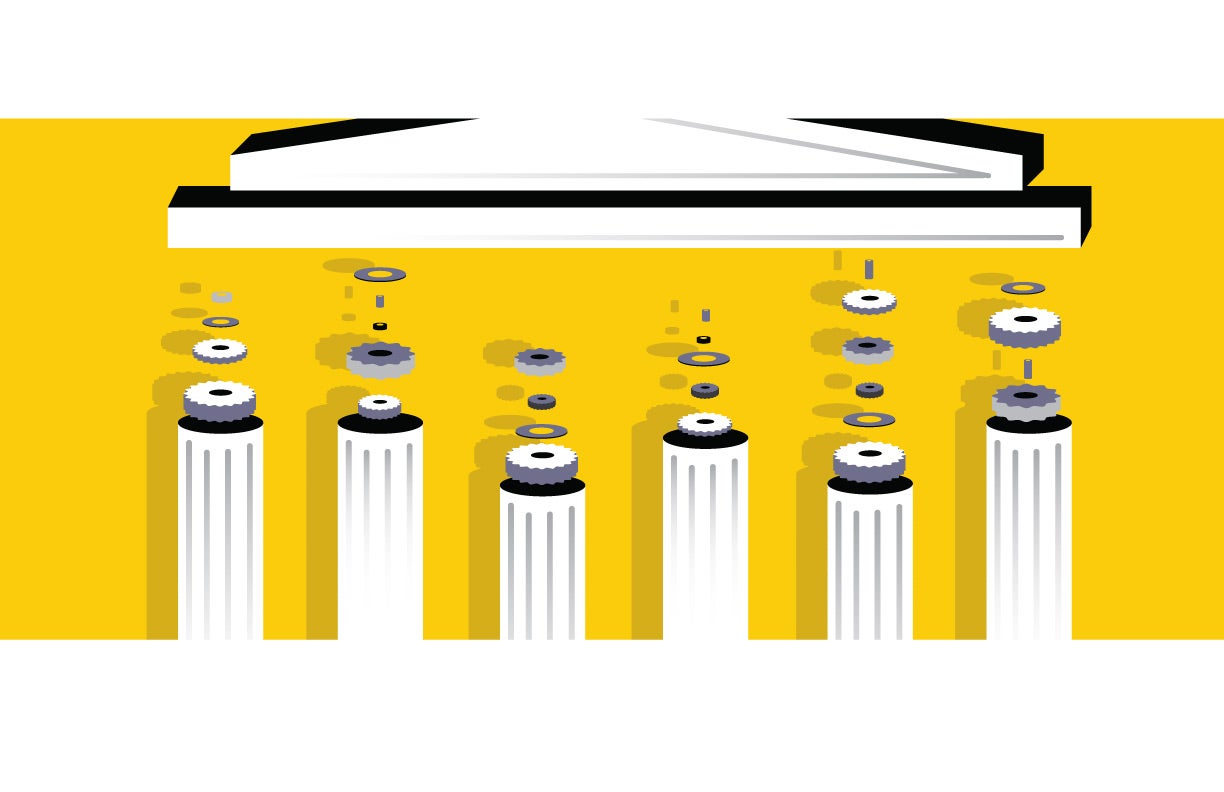

The result, Lazarus wrote, is that the elite bar “may be skewing disproportionately the Court’s docket and rulings on the merits in favor of those moneyed interests more able to pay for such expertise.”

In the years since, several other scholars have been inspired by Lazarus’ “unique and seminal” work to do additional research, said Assistant Professor Andrew Manuel Crespo ’08, who clerked for both Justices Kagan and Stephen Breyer ’64.

Crespo’s forthcoming law review article examines sharp disparities in the quality and expertise of lawyers representing criminal defendants before the Supreme Court. Reuters also did a multipart investigative series explaining the rise and impact of the Supreme Court bar to a general audience, he noted.

“Richard identified the emergence of an elite Supreme Court bar and, more importantly, its growing impact on the institution. Before his study, a small group of insiders may have been aware of the phenomenon, but it had not been studied from a scholarly perspective, or brought to the public’s attention,” Crespo said.

After reading a more recent paper by Lazarus using statistics to analyze the chief justice’s administrative and assigning authority, Crespo said he suspected even the justices are learning something about the Court from his scholarship.

“It is a testament to the comprehensive detail and the nuance of Richard’s work that a Supreme Court justice could read it and learn something new about how the Court functions as an institution,” Crespo said.

Lazarus said he gets no special insider information about how the Court functions from his law school classmate Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. ’79, with whom he has taught a summer seminar throughout Europe and in Japan.

“We’re good long-standing and loyal friends, but we don’t mix the two,” he said. “I don’t know what he’s working on, and he doesn’t know what I’m working on.”