While many young people disdain the political process, some recent HLS alumni seek elective office to help their communities

Four months after John Cranley ’99 filled a vacant seat on the Cincinnati City Council, local police shot an unarmed black man in the heart. The city erupted in three days of race riots–rock-throwing, smashed windows, fires, tear gas, rubber bullets. Cranley was 26, a fresh-faced city council member, and chairman of the council’s finance committee.

“Talk about baptism by fire,” Cranley said. “This is my hometown, and we were coming apart at the seams.”

While most people his age are either working in the private sector or still fumbling with life after school, Cranley and several other recent Harvard Law graduates have found their niche in politics. With only 12 percent of people between the ages of 15 and 25 expressing a high interest in running for office, these alumni challenge the notion that young people are cynical, lazy, and uninterested in public service. They have eschewed prestigious law firms, forgone six-figure salaries, and returned to their hometowns hoping to make a difference from the inside out.

Cranley’s path to politics began at 17. He was in the Dominican Republic volunteering at an orphanage when a 5-year-old girl–so malnourished she could neither walk, talk, nor respond in any way–arrived with her older brother. The night before, their mother had abandoned them at the side of the road. For two days straight, Cranley held the little girl. He made faces at her and talked to her, hoping for a reaction, or even a cry. But she never responded. “It was like talking to the woods,” he said.

After being away from the orphanage for several weeks to complete community service activities elsewhere in the Dominican Republic, Cranley returned. The little girl was crawling on the floor, smiling, and laughing. Cranley was flabbergasted.

“It restored my faith that change is possible,” he said. “At that time, I was debating all sorts of career choices. After that experience, I resolved that I’ve got to do something that will result in a better society.”

Cranley returned to Cincinnati after graduating from HLS, eager to get involved in a local campaign. He got his wish and then some. When no one surfaced to challenge Republican Congressman Steve Chabot in 2000, the Democrats tapped Cranley, one of the youngest people to run for Congress that year.

So young, in fact, that he made the perfect subject for an MTV Choose or Lose documentary. While Cranley did not have much name recognition in his district, the TV cameras trailing him helped lend a sense of seriousness and importance to his campaign. He could walk into a church festival of 1,000 people, and even if most of the attendees had no idea who he was, the TV cameras made them take notice.

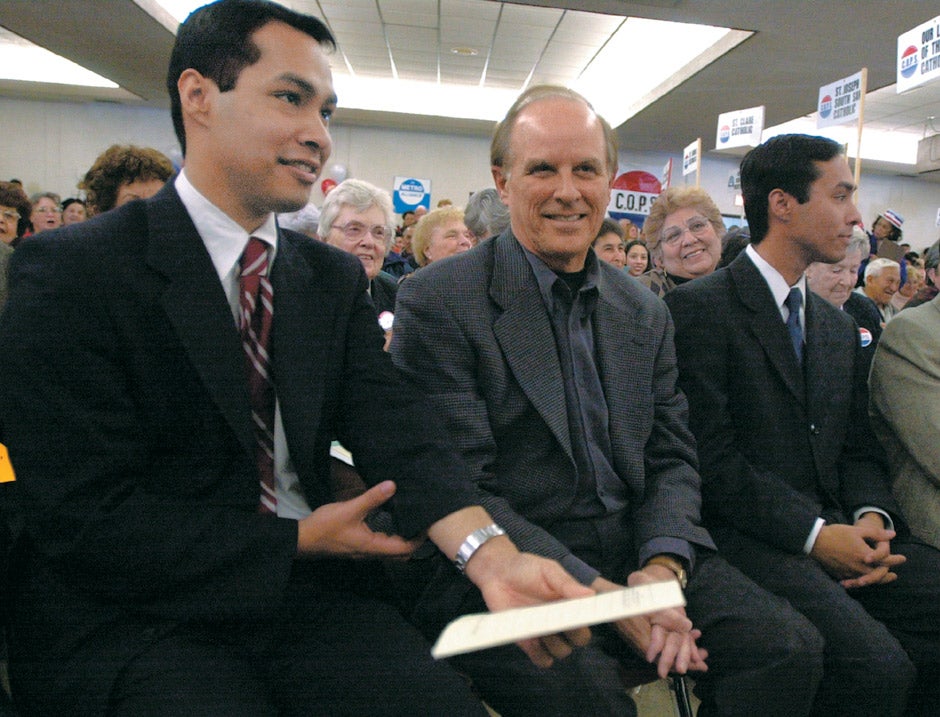

Credit: San Antonio Express City Councilman Julian Castro ’00

He ultimately lost his bid for Congress, garnering 44 percent of the vote. Now he sits on the Cincinnati City Council during one of the city’s most tumultuous periods.

“While it’s not necessarily common for young people to run for office, our generation is so committed to activism and service that, over time, there will be an interest in politics,” he said. “I genuinely believe in democracy, and I feel like it’s a place where I can make a difference and try to rearrange the power structure.”

But, for these alumni, it’s not an interest in rearranging the power structure on a grand scale–at least not yet. They are motivated foremost by the desire to make a community they know well a better place to live.

When Joaquin and Julian Castro ’00 (pictured together at top of page) entered Harvard Law School in 1997, they knew they would eventually return to San Antonio. During his first year, Julian even began planning for his city council race, which he won last year. Joaquin is now set to face a young Republican for a seat on the state legislature.

For the Castro twins, being away from home (first at Stanford, then at HLS) gave them the perspective they needed to return home to run for office. “I always thought that those people we were sitting with at HLS were not that different from who we were sitting with in high school,” Joaquin said. “And I wondered why there weren’t more of us at Harvard.”

Joaquin and Julian resolved to return home and show young people there that schools such as Harvard and Stanford are options. Both brothers say their education away from home broadened their worldview and showed them that politics matter. But even before that, their mother showed them as well. Rosie Castro ran for city council 30 years ago as a candidate for La Raza Unida Party. Although she did not win a seat, she remained active in the Chicano movement. Julian remembers handing out leaflets for a mayoral candidate when he and Joaquin were just 3 or 4 years old.

“Seeing her being very involved made us think that it was usual or normal to get involved in politics and public policy,” Julian said. “It made such involvement more attractive than it might be if we did not grow up in that environment, if we had folks who shunned politics, or regarded it with distaste.”

Joaquin recognizes that their interest in politics at such a young age may make him and his brother different. But he says most young people would take an active interest in politics if they only understood its importance.

“When young people are cynical, it’s often because they don’t make a connection between the rhetoric of politics and how those policies actually affect their lives,” he said. “Whether the Congress allocates money for Pell Grants is a real issue that can affect whether someone goes to college. When people can’t afford to send their child to college, that’s not a Republican or a Democratic problem. It’s just a problem.”

Credit: Tony Loreti Jalila Jefferson ’01, in Cambridge recently for her Harvard College reunion, ran in May for a seat on the Louisiana Legislature.

Like Joaquin and Julian Castro, Jalila Jefferson ’01 returned to her hometown to run for office just months after graduating from HLS. Also like the Castro twins, Jefferson has an abiding interest in providing educational opportunities for young people and a parent who is politically involved: U.S. Rep. William Jefferson ’72, D-La.

Jefferson moved to Los Angeles with her fiancé after graduating from HLS in 2001. She worked at the firm Quinn Emanuel Urquhart Oliver & Hedges for five months and had every intention of staying in L.A. for several years. But when a Louisiana state representative won a seat on the New Orleans City Council, Jefferson could not pass up the opportunity to return to New Orleans and run for the legislature. She resigned her job and flew home just in time to qualify for the race.

Running for office was always something Jefferson considered, but she wasn’t sure she would take the plunge until her third year at HLS.

“Coming out of Harvard Law School, you have so many options,” Jefferson said. “I had been praying very hard about what I should do with my life. It doesn’t always have to be a big law firm; in fact, I wasn’t very happy at that job in Los Angeles. I didn’t know exactly what direction I should be heading in. And it just came to me, and I thought it would be so gratifying.”

Despite her father’s name recognition and connections that helped her raise a significant amount of money, she lost the special election by 110 votes. The press in New Orleans emphasized her familial political connections and accused her of a sense of entitlement. Jefferson, who is African-American, asserts that such accusations stem from a deep-seated bias against black political candidates in the South. Though U.S. Sen. Mary Landrieu from Louisiana has several relatives in public office, including a father who was the mayor of New Orleans, no one talks about family dynasties when it comes to the Landrieus, Jefferson contends.

“They’ve got at least four or five people in elected office, and that’s OK. It never comes up,” she said. “But when a black family wants to come and do it, we’re trying to run the entire city.”

Since the race Jefferson lost was a special election to fill a vacant seat, it will be up for grabs again in November 2003, when Louisiana residents will also vote for governor. Jefferson expects to take another crack at the seat then and benefit from higher voter turnout. In the meantime, she plans to launch a foundation devoted to education, which she says is her top priority. She also plans to organize a voter registration drive, particularly in the city’s African-American communities, where voter turnout is historically low.

Michael Gianaris ’93 got his start in politics in a voter registration drive. It was during Michael Dukakis’ (’60) campaign for the presidency, which ignited the political fires under the Greek population in Astoria, Queens, where Gianaris grew up. He chaired a group called Young Adults for Dukakis and registered 10,000 voters in one small pocket of New York City. Now Gianaris, at 32, is the second-youngest person in the New York State Assembly. He traces his election in 2000 to that voter registration drive 12 years earlier. Many of those he saw at the polls voting for him were people he helped register in 1988, he says.

Despite his experience as an aide to a congressman, as Governor Mario Cuomo’s Queens County regional representative, and as associate counsel to the state Assembly, Gianaris says he remains skeptical of politics, and he can understand why young people might have an aversion to it.

“I’m cynical today, and I’ve always been cynical about politics,” he said. “But politics is the realm where decisions are made. One can take a pass and let others make decisions for them, or get involved. Getting involved in that process can be ugly, and I learn every day that it gets uglier and uglier. But I would rather be involved in the process than sit back and complain and have others make decisions for me.”

That involvement comes at a price, says Gianaris, who worked for two years as an attorney at Chadbourne & Parke. “There’s a great deal of sacrifice necessary to work as a politician,” he said. “But it is more than worth it. Do I take the $150,000-a-year job, or do I find something that might be more interesting and more gratifying? I’ve done both, and without question, I chose something more satisfying. The feeling of waking up excited and happy to get on with the day and go to work is immeasurable in value.”

Brian Blais ’04 hasn’t even graduated yet, and he knows the feeling Gianaris is talking about. He began his first year of law school while running a campaign for city council in his hometown of Woonsocket, R.I. From the beginning of classes early last September to the election in November, Blais traveled from Cambridge to Woonsocket several times a week to shake hands with voters and get out his message. Fearing that his peers would brand him a calculating politician, Blais informed only a few of his section mates of his campaign as the election approached.

Out of 14 candidates running for seven seats, Blais came in third, a result he never expected. His pledge to help end factionalism and infighting on the city council resonated with voters. Now he plays an influential role on the council: Three of the members are supporters of the mayor, three are detractors. On issues that divide the supporters from the detractors, Blais represents the swing vote.

Blais says that his position on the city council has not diminished his ability to excel in law school. Before entering HLS, he worked 80 to 100 hours a week as an investment banker in New York City. He says the number of hours his studies and political responsibilities require is nothing in comparison.

“If I spend four or five hours a week working on city council matters, that’s a lot,” he said. “It doesn’t take a lot of time, but at the same time, I’m able to do meaningful things that actually impact people. It’s sort of a perfect thing to do while I’m in law school without overwhelming myself. The two together actually complement each other very well.”

While his parents are largely apolitical, Blais has been engaged in politics ever since he watched a Woonsocket City Council meeting on public access television when he was 13. He recalls being impressed by the substance of the discussion and how it could affect the residents of the city. In high school, he served as a party functionary for both the local and state Democratic parties. As an undergraduate at Harvard, he completed two government internships in Washington, D.C.

Like Cranley, the Castro twins, Jefferson, and Gianaris, Blais views local politics as a chance to do something worthwhile, something measured and tangible. When a constituent complains about a pothole in front of his or her house, Blais can call public works, ask a crew to fix that pothole, and easily make a difference.

“Politics is, in many senses, viewed as dirty, as something dignified people don’t do,” he said. “I think that’s unfortunate, because I think public service, like it was 50 years ago, is an honorable thing. In many ways, there are so many things we can do that affect people’s lives, that can make people’s lives better. Maybe I’m anachronistic and old-fashioned, but I think public service is an honorable profession, and having the chance to do it is for me an honor. As a 26-year-old, I’m humbled by the fact that people put their confidence in me and said, ‘Yes, we want you to represent us.'”