Is it getting harder for the government to take away your land?

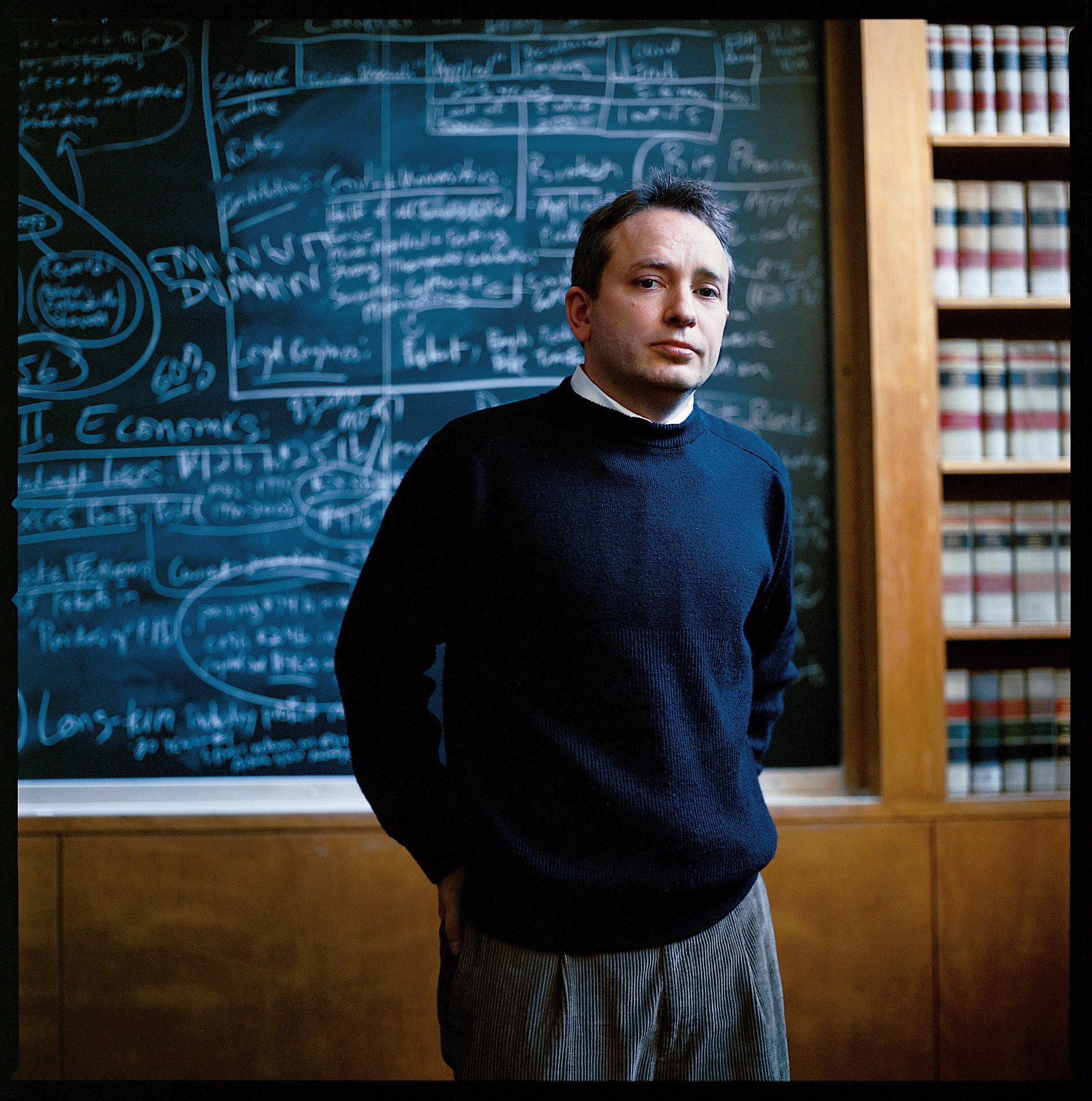

Local governments have long had broad authority to accomplish urban planning through the power of eminent domain–taking land away from private owners for fair market value and converting it to uses that meet public needs. But a string of recent court cases has cut back that authority, especially where governments have condemned property and made it available to other private owners more likely to boost tax revenues. A case now pending in the U.S. Supreme Court, Kelo v. City of New London, could define new limits on the power of eminent domain. The Bulletin asked HLS Professor David Barron ’94, an expert on local government law, to explain what’s at stake and what he thinks the Court should do.

“Pushed by a growing property rights movement,” said Barron, “several courts have recently made it clear that they will not simply accept a city’s assurances that taking private property and transferring it to another private entity for development will serve a public end. They have relied on the Constitution’s Takings Clause, which permits the government to take private property (and pay just compensation) but only for a ‘public use.’ A public use, these courts say, is not the same as a public purpose. If the Supreme Court follows the trend of these cases in Kelo, cities will increasingly be prohibited from engaging in certain kinds of land-use planning, even if they are willing to pay compensation. This would be cause for concern. It would preclude cities from entering into many public/private redevelopment partnerships and put an end to a lot of much-needed urban redevelopment.

“But that doesn’t mean the Court should conclude that the ‘public use’ requirement has no teeth. Concerns certainly arise when cities take property from individual landowners or small businesses–for example, a 99 Cents Only store–and transfer it to big private entities like Costco solely to boost their tax base. It’s troubling that many local governments now use their land-use power not as a means of carrying out new public visions for their cities’ futures but as a narrow tool for making up budget shortfalls. The Court should recognize an important distinction between a transfer of land to a private party as part of a broader public land-use plan and one that is purely fiscal.

“Unlike some recent cases where the takings were thinly veiled revenue-raising exercises, in Kelo the takings are part of a real public land-use plan. Connecticut has classified New London as a ‘distressed municipality,’ and one of the plan’s purposes is explicitly to promote economic development and create jobs. But that should not make the plan unconstitutional. Every redevelopment plan seeks to improve the city’s economic position. What’s critical is that New London is attempting to implement a wide-ranging plan to change how the public will use an important part of the city. The goal is to develop 90 acres, near both a state park and the Pfizer global research facility. The plan includes a public walkway, new residences, office buildings, parking, a marina, a new hotel, and developing a new use for an old military facility. The fact that property is being transferred from some private owners to others should not be disqualifying. It’s part of what makes such a bold public land-use plan possible.

“By affirming New London’s exercise of the power of eminent domain on the ground that it constitutes a legitimate land-use planning effort, the Court would protect private property rights and provide a check against cities using takings as simply a fiscal tool. Tying a planning requirement to the ‘public use’ test would stimulate local government planning because, whenever a transfer of the condemned land to a private party was involved, the taking could pass muster only when it was part of a real urban land-use plan.”