What does it mean to “think like a lawyer” – in particular, an American lawyer?

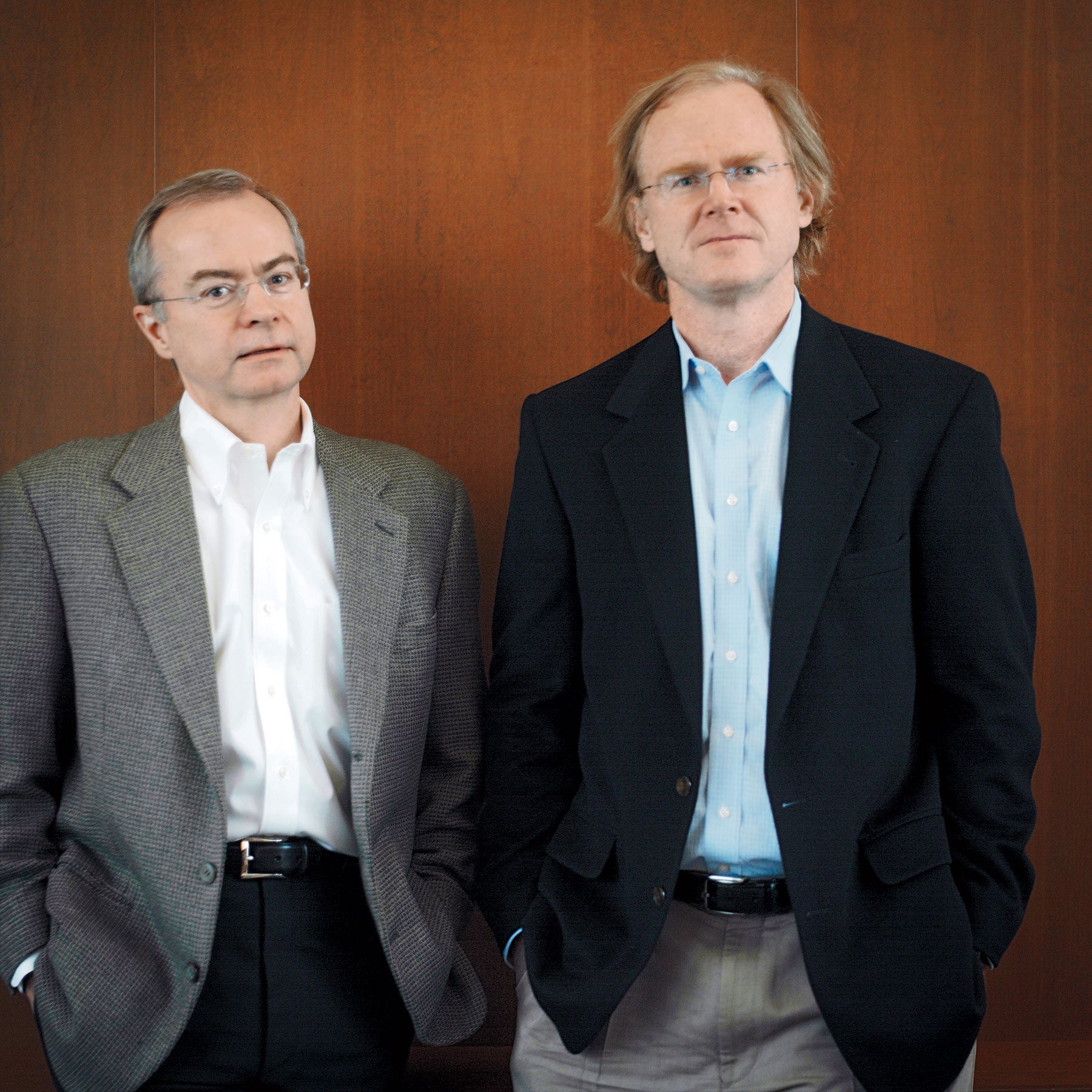

Credit: Leah Fasten Professors David Kennedy and William Fisher offer up the 20 articles they believe have been most influential in shaping American legal thinking.

After wrestling with that question for years, Harvard Law Professors David Kennedy ’80 and William W. Fisher III ’82 have given us an anthology of the law review articles they believe yield the answer. “The Canon of American Legal Thought” (Princeton University Press, 2006) brings together the 20 articles they deem to have been most influential in shaping American legal thinking and a distinctly American style of reasoning across the twentieth century.

Harvard Law School’s alumni and professors are well represented throughout the 925-page collection. A third of the articles first appeared in the Harvard Law Review. Authors include HLS professors and alumni ranging from Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes LL.B. 1866 and former HLS Dean Albert Sacks ’48 to current Professors Duncan Kennedy and Frank Michelman ’60.

Each article is introduced by an essay from Fisher or Kennedy situating “the work in the authors’ trajectory and in the intellectual climate of the era,” says Fisher. The editors divide the canon of American legal thought into eight schools, including Legal Realism, The Legal Process, Modern Liberalism, Law and Economics, and Feminist Legal Theory. While those labels are familiar to many students and practicing attorneys, Kennedy says their ideas are too often reduced to mere shorthand. “Indeed, we were both struck by the intellectual sophistication with which so many of the cliches of everyday legal argument were originally formulated,” he adds.

The editors say the collection shows a rhythm that has been repeated for more than a century: A single idea or “orthodoxy” dominates for a while, then a “critique” follows, and finally there is fragmentation, when consensus breaks down. For example, the formal rules of classical legal thought were criticized in the early 20th century by functionalist, pragmatic and “legal realist” modes of reasoning. After the Second World War, a new consensus emerged which focused on the legal process and the legitimacy of institutional arrangements. Starting in the 1960s, Fisher and Kennedy explain, the Legal Process “consensus was in turn itself shattered by the emergence of an array of methodologies associated variously with economics, sociology, liberal theory and the work of critical legal studies scholars.”

They call the years since 1960 “the emergence of eclecticism,” in which no single idea dominates. “Whether in some future moment legal consciousness will be consolidated as in the late 19th century or postwar period, it’s very hard to know.”

In deciding what to include, Fisher and Kennedy consulted many colleagues and students over the years, looking for articles that represent methodological innovation and that are consistently used in teaching.

They hope the collection will be useful to many audiences. “The most obvious one,” says Fisher, “is law students hungry for immersion in the theoretical materials of which they ordinarily get snippets in their classes. Those tend to be unsatisfying because they are not connected to full-blown arguments.”

Kennedy says the book should also prove helpful to law professors “who are presumed to know these texts but may never have read them whole or with bibliographical notes.” Finally, he adds, he hopes there’s a broader audience among lawyers: “The volume can take them back to the best days of law school” and give them occasion “to reflect on whether what they learned still makes sense.”

View More

Twenty for the ages

Kennedy and Fisher’s picks

Illustration by Nora Krug

- Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. LL.B. 1866, “The Path of the Law” (1897).

- Wesley Hohfeld LL.B. 1904, “Some Fundamental Legal Conceptions as Applied in Judicial Reasoning” (1913).

- Robert Hale LL.B. 1909, “Coercion and Distribution in a Supposedly Noncoercive State” (1923).

- John Dewey, “Logical Method and Law” (1924).

- Karl Llewellyn, “Some Realism About Realism—Responding to Dean Pound” (1931).

- Felix Cohen, “Transcendental Nonsense and the Functional Approach” (1935).

- Lon L. Fuller, “Consideration and Form” (1941).

- Henry M. Hart Jr. ’30 and Albert M. Sacks ’48, “The Legal Process: Basic Problems in the Making and Application of Law” (1958).

- Herbert Wechsler, “Toward Neutral Principles of Constitutional Law” (1959).

- Ronald H. Coase, “The Problem of Social Cost” (1960).

- Stewart Macaulay, “Non-Contractual Relations in Business: A Preliminary Study” (1963).

- Guido Calabresi and Douglas Melamed, “Property Rules, Liability Rules, and Inalienability: One View of the Cathedral” (1972).

- Marc Galanter, “Why the ‘Haves’ Come Out Ahead: Speculations on the Limits of Legal Change” (1974).

- Ronald Dworkin ’57, “Hard Cases” (1975).

- Abram Chayes ’49, “The Role of the Judge in Public Law Litigation” (1976).

- Duncan Kennedy, “Form and Substance in Private Law Adjudication” (1976).

- Catharine A. MacKinnon, “Feminism, Marxism, Method, and the State” (1982-1983).

- Robert Cover, “Violence and the Word” (1986).

- Frank Michelman ’60, “Law’s Republic” (1988).

- Kimberlé Crenshaw ’84, Neil Gotanda LL.M. ’80, Gary Peller ’80 and Kendall Thomas, eds., “Introduction,” “Critical Race Theory: The Key Writings that Formed the Movement” (1996).

From “The Canon of American Legal Thought” (Princeton University Press, 2006). See Reviewing the reviewers.