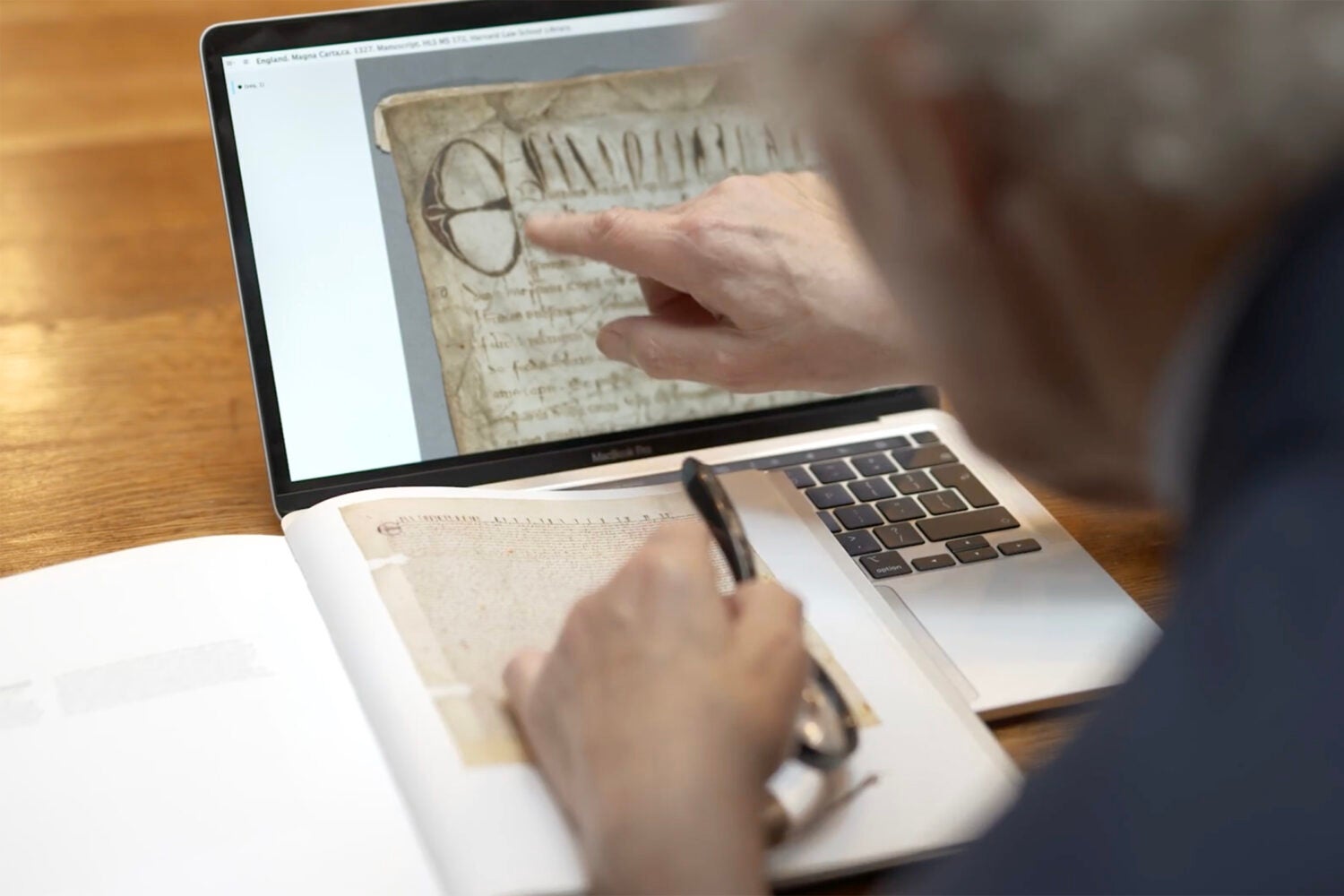

When two British researchers recently decided to take a closer look at a Magna Carta in the Harvard Law School Library archives, they didn’t hop the next flight to United States. Instead, they fired up their laptops and searched the library’s online catalog.

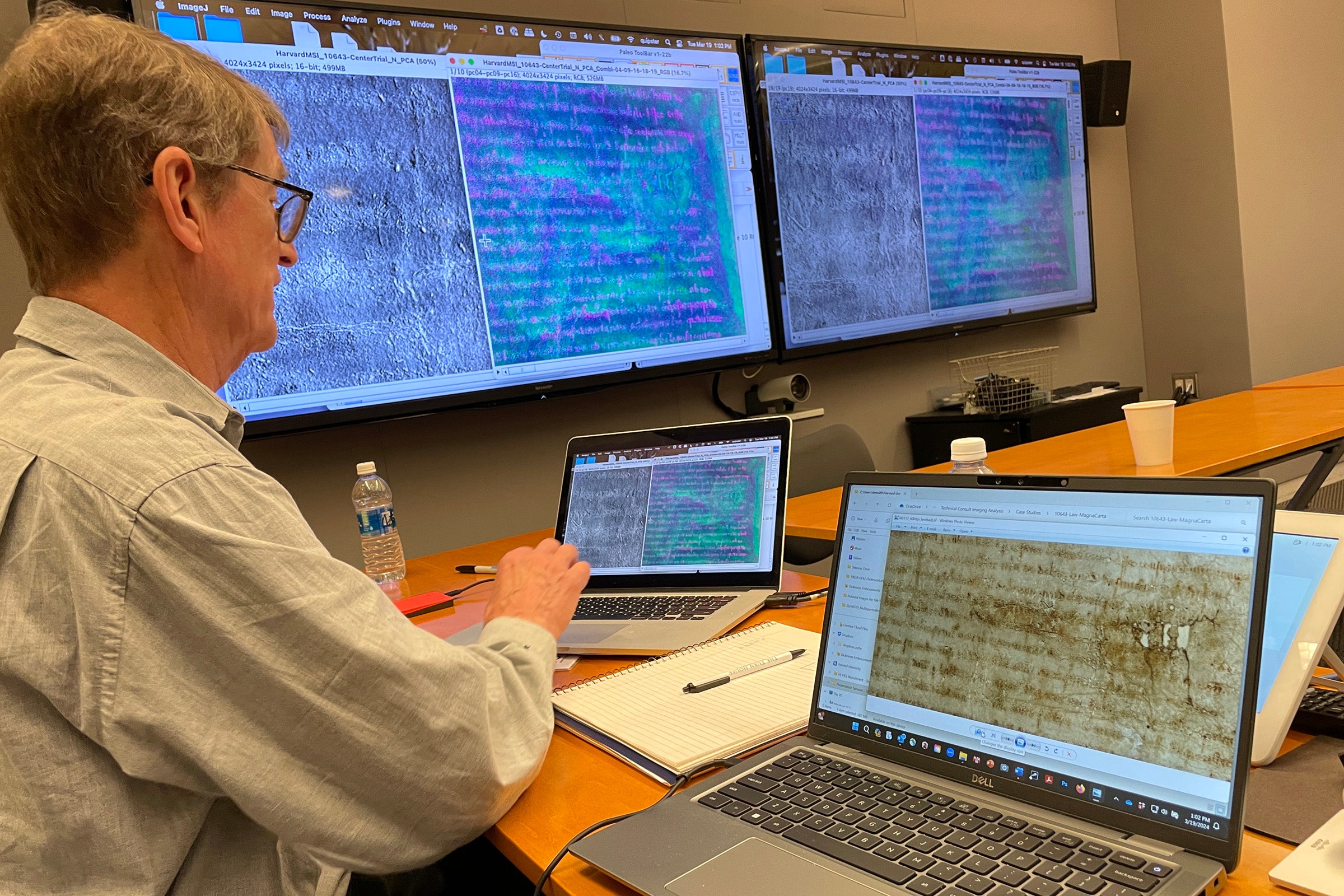

Examining the document online, leading Magna Carta experts David Carpenter and Nicholas Vincent, professors of medieval history at Kings College London and the University of East Anglia, were able to determine that the medieval manuscript was no mere copy of the great medieval charter, as had been believed. Instead, the image on their screens, they realized, was that of a rare original, making it one of seven from King Edward I’s 1300 confirmation of Magna Carta that still survive.

‘HLS MS 172,’ as the document is known to researchers, is just one of the thousands of treasures in the law library’s vast holdings that have been digitized in recent decades, enabling scholars or just curious members of the public to explore rich pieces of history, personal archives, legal records and more from thousands of miles away. This work enables people around the globe to “take a look at an artifact and scrutinize it patiently, closely,” and to request additional imaging to support their research, says Jonathan Zittrain ’95, George Bemis Professor of International Law and the law school’s vice dean for Library and Information Services.

Harvard Law Today spoke with Amanda Watson, Harvard Law School’s assistant dean for Library and Information Services, about the importance of opening up the library’s collections to the wider world.

Harvard Law Today: When did the Harvard Law School Library begin digitizing its materials and why is this work so important?

Amanda Watson: This work began in the 1980s as part of an effort to make our rich resources available to those beyond Harvard’s gates. Such an important part of the work that we do here is connecting people from around the world to our incredible collections. We have a fantastic medieval manuscripts, but we also have so much more, everything from the Charles Ogletree papers, a contemporary archive we’re digitizing now, to thousands of documents connected to the post-World War II International Military Tribunals, which includes the Nuremberg trials and the Japanese war crimes tribunals we are about to start working on. All of these projects take what we do further, beyond just serving our faculty and students, connecting a global audience to our rich collections. It’s a priority for us to be able to open our collections up and invite the world in.

HLT: What does the digitization work entail? Can you describe the process, and is it done at the law school?

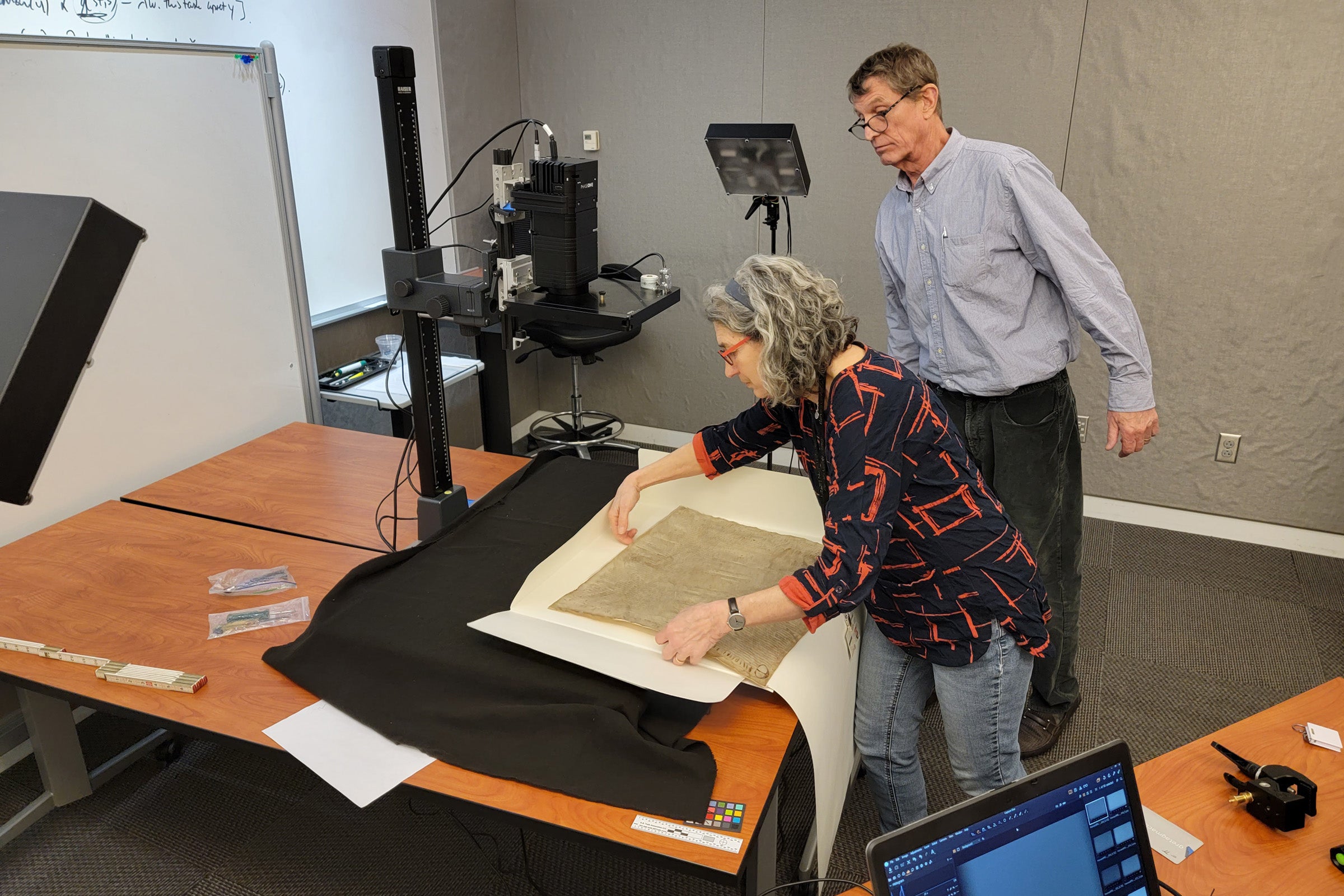

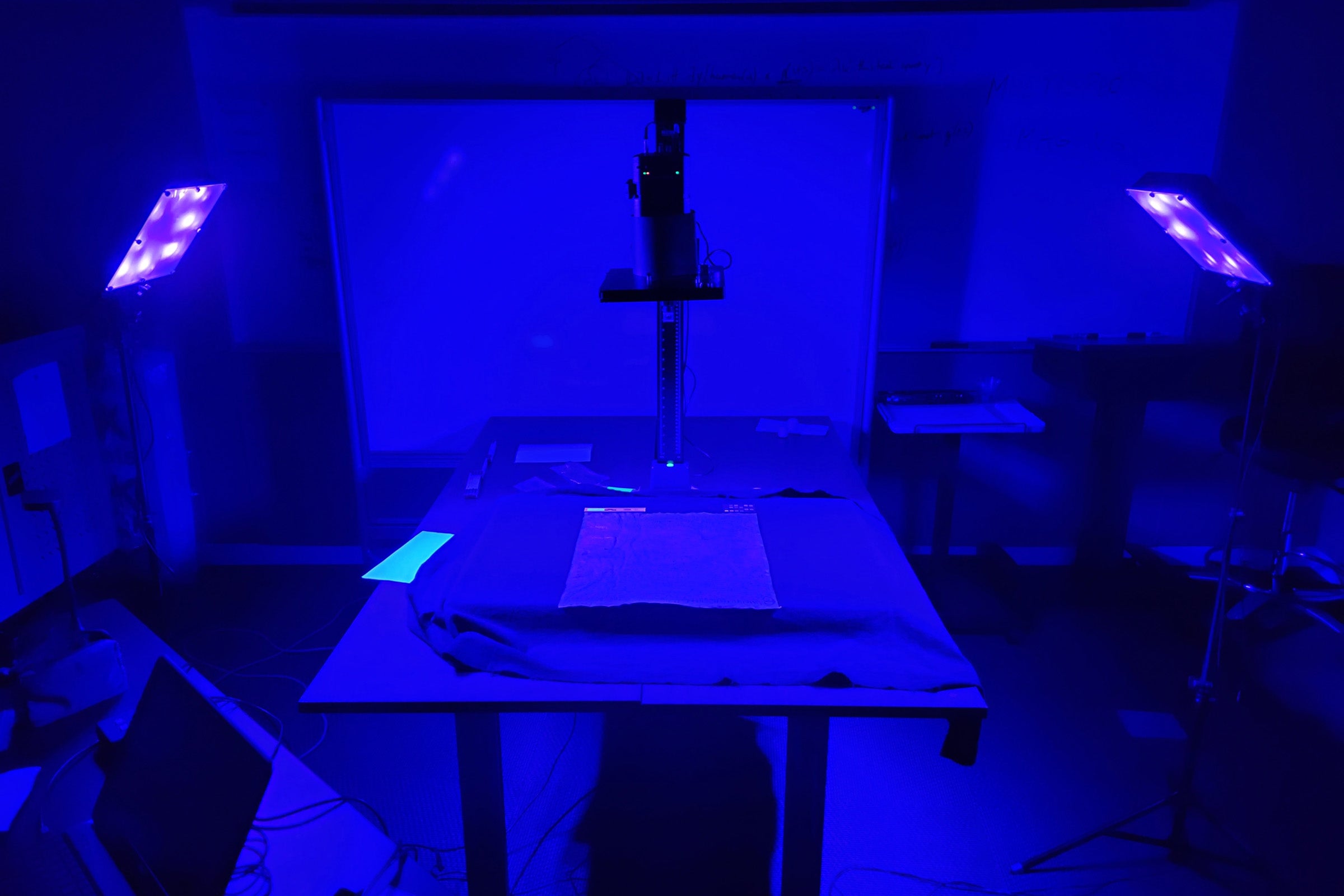

Watson: Harvard Library, which is separate from the Harvard Law School Library, has a beautiful digitization and preservation labs, and we have worked with their experts on a range of projects including this manuscript Magna Carta. The process of photographing these items is a very detailed and delicate — you have to be aware of range of things when capturing images, including how much light something can see and how it can be touched and handled — and our colleagues at Harvard Library have been amazing partners in this careful work. In working with the two British researchers on Magna Carta, we asked our colleagues at Harvard Library to photograph the document at a much higher resolution so that people could zoom in even closer on its details.

HLT: What role does the library team play in making these types of documents available to the wider world?

Watson: When it comes to these types of rare materials, many people picture Indiana Jones with a torch uncovering a treasure in a hidden cave. There certainly are archaeologists doing painstaking work in the field today who are making important discoveries, but we also have scholars like David Carpenter, sitting in the United Kingdom looking at these incredible documents in our collections and surmising, along with his colleague Nicholas Vincent, that the Magna Carta in our archive is an original.

But in order for scholars around the world to make the most of our collections there are librarians, archivists and curators who’ve done the important work of not only making these items available online, but also of describing them so that researchers can find them. How can you search for something if it doesn’t have a description, an index or a finding aid? So, that work of our unsung library staff is critical.

Also, we make choices every day about what we prioritize for digitization, in part based on the work of our faculty, people like Charles Donahue, the Paul A. Freund Professor of Law, recognized for his contributions to medieval scholarship, and Harvard Law School Professor Elizabeth Kamali, an expert in English law. Together, they can get into the minutia with us and use their knowledge of legal history to help advance our knowledge of preservation and access.

HLT: Can you say more about how your team worked with the two Magna Carta experts to support this discovery?

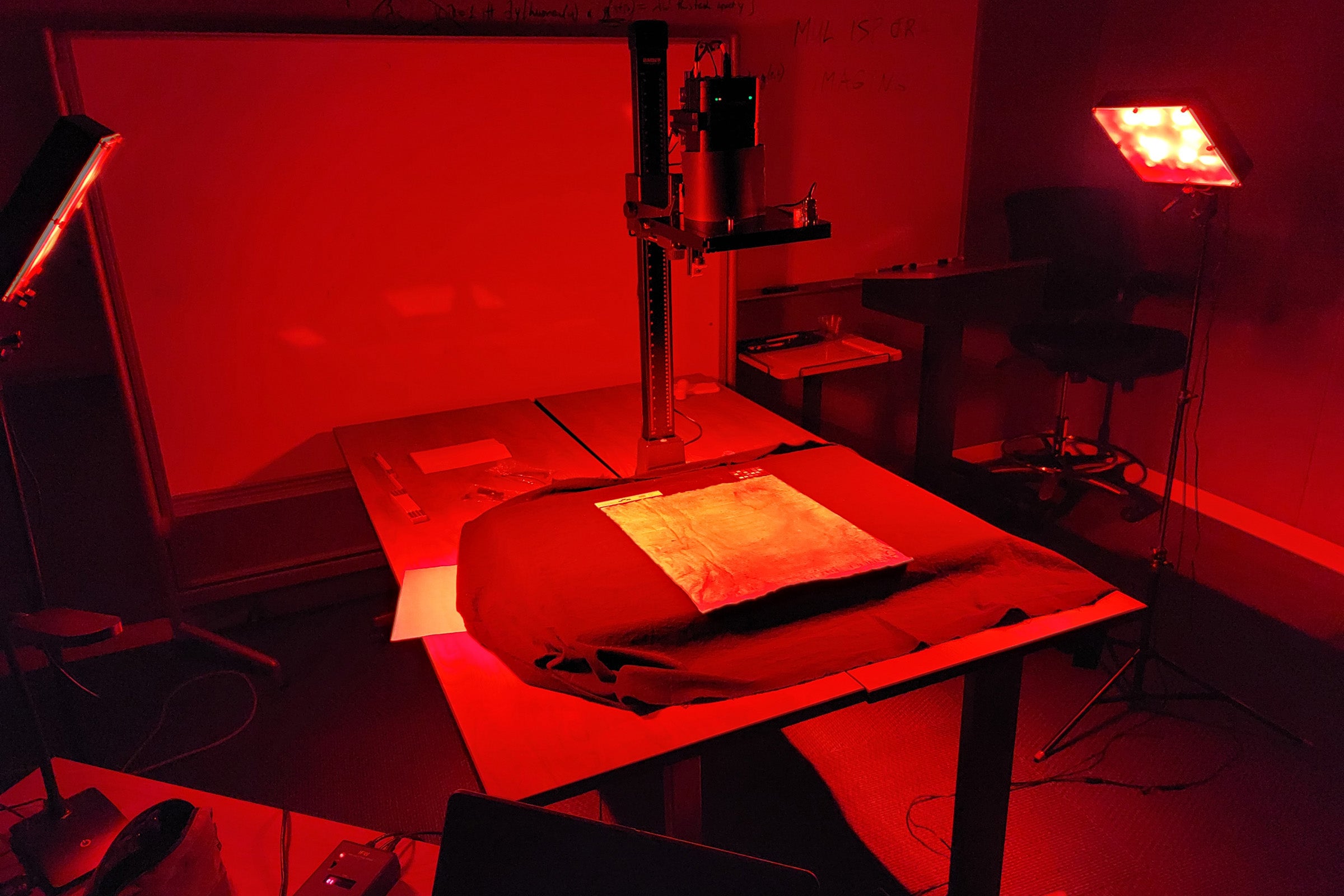

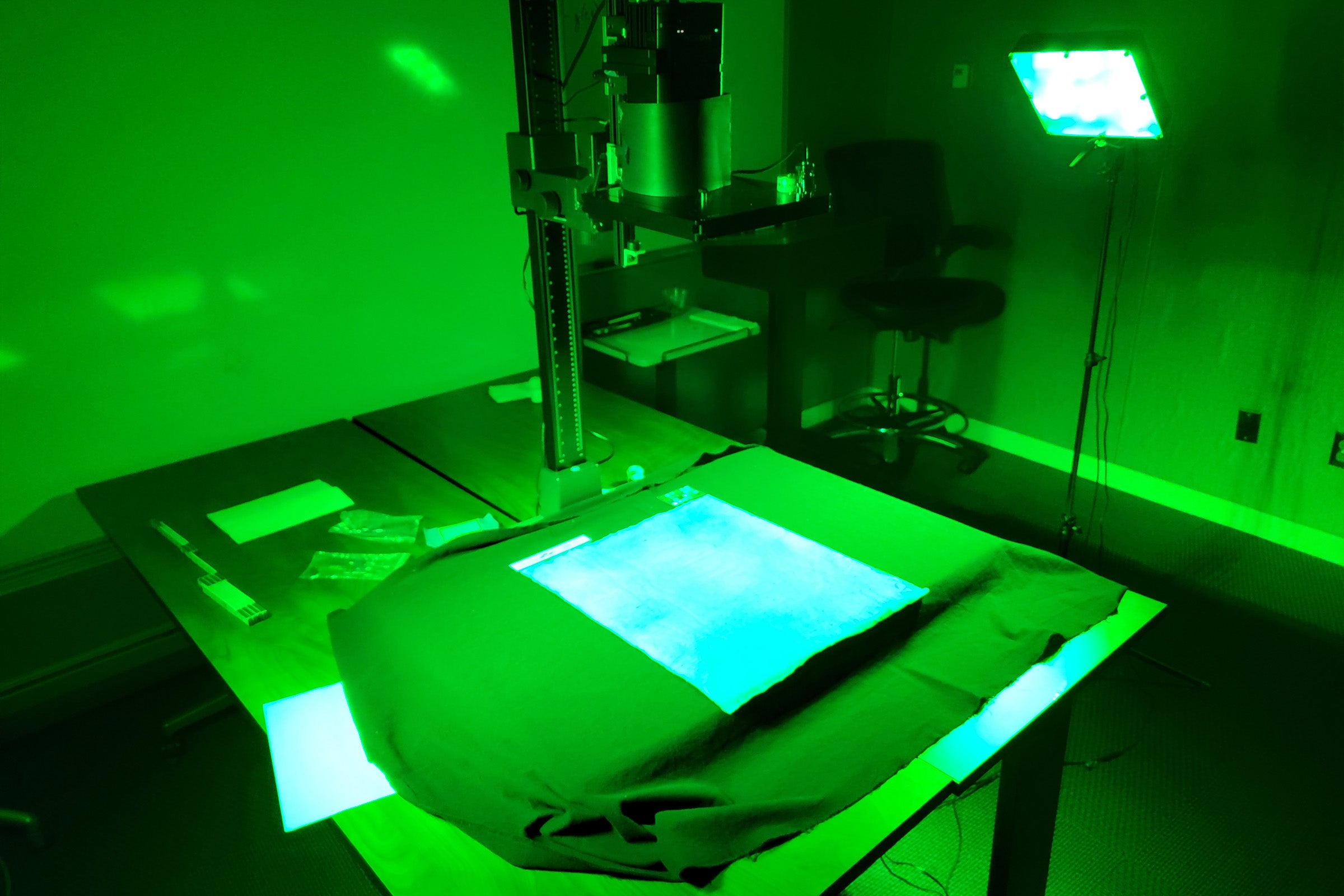

Watson: After they made their initial find by looking at the digitized document on our website, Professors Carpenter and Vincent reached out to the library and asked for us to create some ultraviolet scans so they could look at the document in more detail. We worked with them on that, and they’ve been running full steam ahead to figure out the provenance and trace and how this document got to the auction house where we bought it.

HLT: What exactly is an ultraviolet scan?

Watson: To determine its age, the researchers are looking at the structure of the document, not just reading the words, but looking closely at the composition of the paper and the ink itself. We use a specific kind of camera that can capture incredible detail, and we are planning on sharing those images so the public can also act as citizen detectives, and look closely at the document and do their own investigative work.

HLT: What is it like to have this kind of discovery land in your library? What did that feel like?

Watson: As a librarian, one of the most rewarding things is watching these kinds of connections play out — when we’ve been able to purchase something, keep it safe, love it, give it metadata, digitize it, and then connect a scholar with it, that’s the whole story for us. We felt the same way when we had a scholar come in recently looking for a Polish book. We had it and were able to give it to him and let him use it and he was just overwrought with emotion. We also had a young alum come to see her father’s deposited thesis, and she was in tears. With this Magna Carta, it’s been fantastic to be able to support the researchers’ work, share it with the world, and bring more attention to our historic and special collections.

HLT: Looking ahead, are there any other kinds of new technologies you anticipate using to help digitize the collections further to make them even more available?

Watson: Artificial intelligence has changed everything. A wonderful thing that has happened to us here at Harvard is finding collaborations with groups who are willing to help us digitize our material because they need data to read. From my perspective, it’s a great opportunity for us to get our important collections feeding and training AI, and out into the public. For those projects, we’re working through the Institutional Data Initiative, which is just down the hall and is collaborating with libraries across the globe on exactly this type of work. And we have partners like the Ames Foundation and others who are looking at how technology can support preservation. And it’s happening at a scale that’s much faster and bigger than anything we’ve done before.

Want to stay up to date with Harvard Law Today? Sign up for our weekly newsletter.