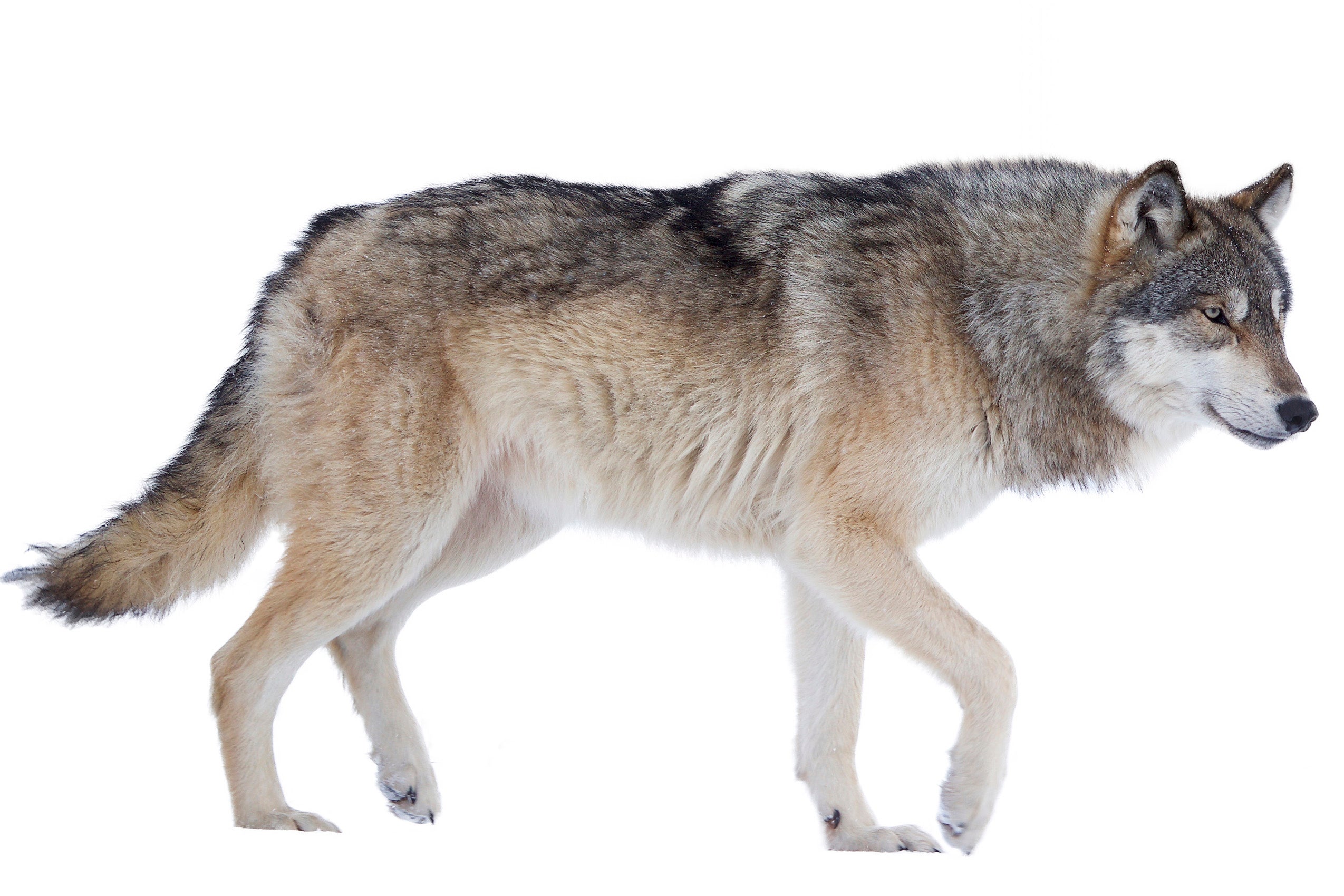

The ravenous fiend who gobbles up Little Red Riding Hood. The big bad wolf who aims to destroy the homes of the three little pigs. From Aesop’s fables to the Grimms’ fairy tales, Western storybooks are replete with negative depictions of wolves, the wilder cousin of the domesticated dog.

Fear of these predators may explain why the estimated population of 2 million wolves that once roamed the American continent from Alaska to Mexico dwindled to almost nothing. Although revered by many Native American tribes, wolves were hunted or harassed to near extinction by the early 20th century by European colonists and settlers, who worried the animals would destroy their livestock and property.

Today, however, it is not uncommon for tourists to spy Canis lupus on a trip to the Lamar Valley in Wyoming or on the craggy shores of Michigan’s Pictured Rocks. In fact, wolves, which serve an important role in the ecosystems they dominate, now number around 7,500 across the continental United States.

The Endangered Species Act has saved some 1,670 plants and animals from extinction.

The charismatic mammal’s comeback story is a bright spot in American environmental history — the result of a bill that attracted little attention when it was signed, but has since become one of the most powerful laws of its kind in the U.S.

That law — the Endangered Species Act of 1973 — recently celebrated 50 years in action and is now responsible for keeping around 1,670 plants and animals from disappearing from the earth forever. But it is not without its controversies.

For one, say Mary Hollingsworth and Andrew Mergen, faculty directors of Harvard Law School’s Animal Law & Policy Clinic and Emmett Environmental Law and Policy Clinic, respectively, the law is activated only when a plant or animal is highly at risk or on the brink of extinction — making a full recovery for the species exceedingly difficult.

And then there are the concerns of landowners and their associates, including developers, ranchers, and miners, who say the law is sometimes applied in ways that violate their property rights or interfere with the realization of other important priorities, such as new housing, food production, and mineral extraction.

Prior to his role at Harvard, Mergen served as chief of the Appellate Section of the Environment and Natural Resources Division at the Department of Justice, where he supervised the litigation of ESA-related cases. He says these fights — about the limits of federalism, the power of government agencies, and public control of private land — mirror many of the biggest debates in American law and society today.

As advocates reflect on half a century of protection for threatened and endangered wildlife, wolves serve as an avatar for the law’s successes — and illustrate how it will continue to be challenged. As we look to the next era of the Endangered Species Act, could the law that protects threatened wildlife itself be under threat?

Quiet beginnings

The Endangered Species Act was born in the midst of a budding environmental movement and a spate of other federal laws aimed at protecting America’s water, air, and wildlife. Passed by a bipartisan coalition in Congress and signed by President Richard Nixon on Dec. 28, 1973, it attracted only modest publicity at the time, says Richard J. Lazarus ’79, the Charles Stebbins Fairchild Professor of Law at Harvard.

Some critics of the law have argued that the ESA unfairly protects plants and animals at the expense of people.

“If you look at The New York Times on the days following the signing, there is a front-page article saying ‘President signs manpower bill,’ which was a job training law. You have to jump to the next page, nearly to the last paragraph of that article, to find a mention of him also signing the Endangered Species Act,” says Lazarus.

But the law nonetheless promised new tools to protect flora and fauna from untrammeled economic growth and unimpeded encroachment.

“The beauty of the law is that it’s not concerned about economic activity,” says Lazarus. “It’s concerned about species, whether or not they have an economic value. It’s a law which recognizes the responsibility that humankind has to all species on our planet.”

It does so in a few important ways, says Hollingsworth, who, before coming to Harvard, spent more than a decade as a trial attorney in the Department of Justice’s Wildlife Environment and Natural Resources Division in the Marine Resources Section, where she defended challenges to rules listing species and designating critical habitat, and enforced the ESA against repeat violators, such as zookeeper Jeff Lowe, who was featured in the Netflix show “Tiger King.”

Hollingsworth points first to Section 4 of the law, which creates listing requirements and empowers all citizens to petition the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service or National Marine Fisheries Service to designate a species as threatened or endangered. Once a species is listed, the agency must also come up with a recovery plan for the plant or animal.

Another key element of the ESA, Hollingsworth says, prohibits the “taking” — meaning killing, maiming, harassing, harming, or even destroying the habitat — of listed species by anyone, including individuals on private land. And there is Section 7, which bars any actions approved, made, or funded by the federal government that could jeopardize the existence of threatened or endangered species. Finally, Section 10 allows for the reintroduction of “experimental populations” of species — such as wolves — in parts of the country where the plant or animal had once thrived but can no longer be found.

This piece of the law reflects a recognition that recovery of species will require cooperation and collaboration with local governments and private citizens, says Hollingsworth. “Section 10(j) gives the agencies flexibility both to take the steps necessary to conserve species, in this case reintroducing certain populations of the protected species, as well as to develop management programs that consider the concerns of local communities.”

ESA at the Supreme Court

According to Lazarus, the Supreme Court has decided a handful of cases involving the ESA over the years, but two in particular cemented the law’s broad reach.

In Tennessee Valley Authority v. Hill, decided in 1978, the Court heard a challenge by farmers and environmentalists to the construction of a multimillion-dollar dam — which had been supported by Congress and was, in fact, already mostly built — due to the existential threat it posed to a subspecies of the snail darter, a small freshwater fish. In a move that shocked many of the dam’s supporters, the 6th Circuit Court of Appeals, noting Section 7’s unequivocal language, issued an injunction preventing the project from being completed.

Despite initial skepticism, even outrage, from some members of the Supreme Court, the majority nonetheless agreed — the law was clear, they said. “When the justices actually read the briefs and looked at the statute — in other words, didn’t just think about it impulsively based on their instinct — they affirmed, 6 to 3,” Lazarus says. “The opinion was written by none other than Chief Justice Warren Burger, a conservative.”

The Court’s decision showed that the ESA was “a serious law that has some very important overriding purposes,” Lazarus adds.

But the win also came with an asterisk attached. After the decision was issued, hoping to reclaim some power, Congress created a committee of seven senior administrators (six from the federal government) — dubbed the “God Squad” — who may, by a super-majority vote, exempt projects from the requirements of the law. Still, Lazarus says, the decision was “a huge victory.”

The other key case was 1995’s Babbitt v. Sweet Home Chapter, Communities for a Great Oregon, involving Section 9 of the law, the one that prevents the taking of an endangered species. A group of landowners sued after the Department of the Interior further interpreted “harm” to an at-risk species to include material changes to its habitat that kill or injure it.

Here, again, the Court sided with environmentalists, holding that habitat destruction could legitimately be considered harm under the act. The decision was “fighting words” to some, Lazarus says, because it applies to, and thus can significantly limit, landowners’ use of their private property.

“As more species have been protected, and there is more understanding about the relationship of habitat to species survival, the more powerful economic interests find themselves restricted by the law,” he says.

Wolves and the ESA

Just days after Nixon signed the Endangered Species Act, the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service added the gray wolf to the endangered list and began working on a recovery plan that would eventually involve the animal’s reintroduction to areas where it had once thrived.

John Leshy ’69 was serving as the Department of the Interior’s top attorney in the mid-1990s, when the agency prepared to release wolves into Yellowstone National Park for the first time.

“Number one, they’re so iconic,” says Leshy of the reasons behind the bold move. “They are also a keystone species, and biologists at that time understood that reintroducing them would be restorative of the entire ecosystem in fundamental ways.”

Because the wolf had been eliminated from the region decades before, the agency chose to reintroduce the animals as an experimental population under Section 10 of the ESA. But the provision also required the agency to prove that wolves had, in fact, been extirpated from the area.

“That was one of the many issues that were litigated before the reintroduction,” says Leshy.

Next, the agency had to contend with ranchers, who feared that the animals would prey on their livestock, and who wielded considerable political power in Wyoming, Montana, and Idaho. These tensions between state fish and game agencies and the federal government are common in the Endangered Species Act context, Leshy says.

To win over state governments and their constituents, the federal agency decided to use the flexibility granted by the law to extend protection to wolves only while they remained within the park’s boundaries — meaning that animals that wandered off public land could be removed or even killed.

“I think most people knew that there would be wolves shot, and there were,” Leshy says. “But that was the price you paid to get this thing off the ground. It was a big concession.”

The concession was also challenged, this time by environmentalists, who believed the agency wasn’t going far enough to safeguard the species. But Leshy’s team won these lawsuits, too, and in January 1995, the first eight gray wolves were finally released into the 2.2-million-acre park.

It was a historic moment, and one that proved significant for the animal and the law itself, says Leshy.

“Since then, wolves have expanded across the West,” he says. “We now have wolves in the northern Sierra Nevada Mountains, and in Washington and Oregon, due to natural in-migration. In a way, it’s a harbinger of a broader ecological movement.”

The wolves also helped restore the habitat in Yellowstone. “Previously, the elk population had expanded because they had no predators. The elk ate small plants and trees, reducing vegetation and changing the ecosystem,” Leshy says. “When the wolves returned, the elk numbers plummeted, and the riparian areas came back.”

And wolves have benefited local communities around the park, bringing in revenue from tourists hoping to spot one in the wild, Leshy says. Without question, the efforts were a success, he concludes.

“The more wolves dispersed around the West, the more people became accustomed to it,” Leshy contends. “Now they understand that wolves are not really a threat to ranching, and they are no threat to people. We won the lawsuits, and I think we also won the war in terms of persuading the public of the importance of this law.”

The fight continues

In fact, Fish & Wildlife’s plan to protect wolves has been so impactful over the years that, in 2020, the agency decided to remove the gray wolf from its endangered list entirely, pointing to the animal’s robust populations in the Northern Rocky Mountains and Great Lakes regions.

But advocates at organizations like the Natural Resources Defense Council pushed back, worried that once federal protections ended, the wolf’s recovery would be stopped in its tracks. In a lawsuit against the Fish & Wildlife Service, the NRDC argued that, among other concerns, the agency had failed to consider the wolf’s historic range, says Frank Sturges ’20.

“The Endangered Species Act doesn’t require looking across all of the range where a species used to be,” says Sturges, who represented the NRDC before the district court. “But it does require looking at what the impact of losing that range has on a species.”

Once wolves were delisted, management fell to the states in which they resided, opening the possibility that many would be killed, Sturges says. He points to examples such as Wisconsin, where more than 200 wolves were hunted in a three-day season opened after federal protections ended.

These types of activities, he adds, “could have a devastating impact on the population in that area and could also impact wolves more broadly.”

That’s because wolves need to be able to move freely to maintain healthy populations, he says. “It’s important in the wolf’s life cycle to have dispersal and to go establish new packs, to ensure genetic diversity by moving between packs.”

Sturges says that the NRDC’s suit offered copious evidence about the importance of a large range to the animal. “We dug into the record looking at the scientific studies to make sure our arguments were all grounded in the science, which I think is very important to Endangered Species Act cases.”

The district court sided with Sturges and the NRDC — restoring federal protections for the gray wolf in the lower 48 states.

That was good news for wolves, Sturges says, pointing as proof to a surprising development during litigation. “We found one wolf who was being tracked by radio collar that made it further south in California than any wolf had been in 100 years,” he says. “It’s such a tangible example of what federal protection for a species does, allowing for movement that is important for recovery and especially important for species like wolves.”

Trade-offs

Still, some worry that the ESA unfairly protects plants and animals at the expense of people, including landowners who find endangered species on their property.

“The ESA is used primarily as a means of ‘free’ land-use control by federal agencies, rather than as a means of protecting and reviving endangered species,” argued a 1998 report from the conservative think tank the Heritage Foundation, which also suggested that Congress create a comprehensive system to reimburse property owners whose rights have been affected by the law.

And, in the case of wolves, livestock owners are also impacted. According to Colorado State University Extension, it can be difficult to calculate the number of farm animals maimed or killed by wolves each year, but the financial toll can be damaging for individual ranchers. As Rep. Cliff Bentz of Oregon recently wrote in a letter asking the Fish & Wildlife Service to again delist gray wolves in the West, “Ranchers … must be able to protect their livestock,” he argued. “They should not continue to be hamstrung by unnecessary regulations that over-protect a species that is thriving.”

But while Mergen acknowledges that wolves do kill sheep, cattle, and other animals, he adds that compensation programs exist to pay ranchers for these types of losses.

“There are trade-offs, for sure,” he says. “But I think they are modest.”

ESA at Harvard

Hoping to defend and strengthen the law’s protections, two clinics at Harvard are working on ESA-related issues.

In her prior role at the DOJ, Hollingsworth led the first civil enforcement actions brought by the U.S. against people harming captive endangered and threatened species. Now, at the helm of the Animal Law & Policy Clinic, she says she plans to bring that experience to help more at-risk animals in captivity.

“For many years, the Fish & Wildlife Service was solely focused on protecting wild populations of ESA-protected species, and only recently acknowledged that the law provides equal protections to captive animals,” she says. “As just one example, there are as many captive tigers in the U.S. as there are tigers in the wild. But when people see these animals at roadside zoos, they are desensitized to the species’ plight. It also contributed to a market to trade in these animals, which is detrimental to a species.”

One issue the Animal Law & Policy Clinic has taken on is what Hollingsworth calls “split listings,” where the agency has protected an animal in the wild but not in captivity. Last semester, her clinic submitted a letter to the the Fish & Wildlife Service to prompt it to respond to a petition to protect all Canada lynx — including those kept in captivity.

“As the clinic explained in its petition to end the disparate treatment of captive Canada lynx under the ESA, protecting captive members of vulnerable species is just as important as protecting wild members,” says Rebecca Garverman ’21, a former staff attorney at the clinic. “In this regard, the law is an invaluable tool for advocates to prevent bad actors from harming endangered species.”

Hollingsworth says she and her students will also work to engage other government agencies, such as the Department of Agriculture — which, she adds, is positioned to spot violations of the act in the course of its regular business — to help enforce the law.

“The clinic will look for ways to encourage agencies to educate their employees on Endangered Species Act protections, to improve communications between federal agencies on ESA matters, and to fulfill their responsibility to carry out programs for the conservation of ESA-protected species,” she says.

To that end, environmental law clinic student Adam Schneider J.D./M.P.P. ’25 spent a semester studying a lesser-known provision of the ESA that could help do just that.

“When people talk about Section 7,” Schneider says, “99% of the time, they’re talking about the requirement that agencies don’t do anything that could jeopardize the survival of species. But I was looking at another part — Section 7(a)(1) — that essentially directs all federal agencies to use the powers they have toward the purpose of preserving and recovering endangered species.”

In other words, Schneider adds, the provision is an affirmative requirement, one that is “open and broad” — but one that is “undefined and therefore has seldom been used.”

Because Schneider could find evidence of only around a dozen instances where agencies have proactively created conservation programs under the provision, and because there is little litigation about the issue, he says there could be untapped potential in the provision. “As a clinic, we wanted to examine what kind of support and guidance we can provide to federal agencies so that they have more inclination and ability to take the powers they have and pursue these types of programs.”

Looking to the future

Despite the Endangered Species Act’s success in the courts over the decades, some, citing the Supreme Court’s shifting views on constitutional law and statutory interpretation, sense fresh danger ahead.

Particularly concerning to advocates are attacks on the law’s constitutionality under the Commerce Clause, which gives Congress power to regulate interstate economic activity and ostensibly underpinned its authority to pass the ESA.

John Leshy

“There is a visceral, human instinct

to protect creation,”

“This is the question of, Do you even have the power to protect these species?” says Mergen.

Lazarus says that the more than half a dozen circuit courts that have considered this question over the years have upheld the law based on an “aggregation theory,” or the idea that even if one individual species does not impact the economy, all endangered species taken together do.

But there is some uncertainty about what the Supreme Court might do if a conflict among the circuits emerges. In a concurring opinion last year in Sackett v. Environmental Protection Agency, Justice Clarence Thomas, joined by Justice Neil Gorsuch ’91, decried what he saw as an overly expansive view of the Commerce Clause, specifically calling out the Endangered Species Act as one such example.

Hollingsworth says that the constitutionality of the ESA will depend on whether the Supreme Court continues to buy into the aggregation theory. “If it doesn’t, over a half of currently protected species could lose ESA protection,” she warns.

Mergen himself successfully defended the constitutionality of the ESA under the Commerce Clause in a 2000 case involving red wolves in North Carolina. He believes the act has a clear nexus to interstate commerce.

“The whole reason that people normally want to get rid of wolves, for example, is because they have farm animals they’re worried about. That’s economic activity,” he says. “And often, when we protect these species, there is commerce in the money generated by tourists and those coming to see and experience these animals. That’s also economic activity.”

Advocates also fret about how the Court’s recent decision in Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo, which overturned the longstanding legal doctrine known as Chevron deference, could impact how courts interpret the ESA. In that case, the Court curtailed some of the leeway previously enjoyed by federal agencies in interpreting the statutes they administer.

The holding suggests that if Babbitt — the case involving construction of the word “harm” — were heard today, the Court might decide it differently, says Lazarus.

But he is optimistic that the 1995 decision will likely stand. “Chief Justice John Roberts [’79] made clear in his opinion in Loper Bright that they weren’t applying the decision retroactively, so cases that relied on Chevron in the past would not be disturbed.”

That said, Loper Bright could impact future litigation, Lazarus acknowledges. “If there are other aspects of the ESA which had not previously been subject to Supreme Court review and stare decisis, such as the word ‘species,’ the Court won’t give deference to the agency.”

Even so, Lazarus says that agencies are still entitled to the same deference they have always had in decisions involving the application of law to facts, such as a determination of whether a particular species is endangered or not.

In Mergen’s view, “There shouldn’t be chaos” after Loper Bright. “But the reality is that Chevron has been deployed a lot in the Endangered Species Act context because there are a lot of terms in the statute that require technical expertise to interpret.”

Villains no more

Thanks to the Endangered Species Act, and with help from Homo sapiens, wolves are now returning to places from which they had long ago disappeared, from the mountains of California to the marshlands of North Carolina. Some states, with their residents’ approval, have even voluntarily released wolves on public lands, as Colorado did in 2023. And the animal itself has experienced a stunning PR reversal. No longer the storybook villain, wolves are now viewed positively among 61% of Americans, according to a 2014 study.

The Endangered Species Act has fared even better. In fact, conserving species may be one of the few issues that can unite the two sides of the political aisle: A 2018 survey found that four in five Americans supported the law, with 74% of conservatives and 90% of liberals in favor.

“There are challenges with administering the act,” says Leshy. “But it’s also incredibly popular. And I think that’s because there is a visceral, human instinct to protect creation.”

Lazarus believes the law has been enormously successful — but he, like Mergen, has a significant reservation. “It does a very good job doing what Congress designed it to do, which is protect species that are threatened or in jeopardy of extinction. But that protection is triggered a little late.”

“Waiting until a species is threatened before providing protections does make full recovery challenging,” Hollingsworth agrees. But she says that “the statute can nonetheless be viewed as successful in light of the relatively few threatened and endangered species that have gone extinct after receiving federal protection.”

Lazarus adds that, because the law protects only species at existential risk, “it necessarily has to be very demanding and uncompromising.” What if, instead, the law could act sooner, and therefore impose less draconian measures, he wonders. Could this be a boon for environmentalists and property owners alike?

But until Congress — or the courts — chooses to act, fundamental tensions around the law will remain. What should we protect, and who is responsible for doing so? How do we balance property rights with our desire to protect the plants and animals that depend on that land?

The answers may be once again in flux. But what is certain is that, for the time being at least, the Endangered Species Act is here to stay. And so, it seems, are the wolves.