No one in legal academia has ever combined the roles of constitutional teacher, scholar, advocate, adviser, and commentator with the dazzling breadth, depth, and eloquence of Larry Tribe ’66. And no constitutional law professor has ever so seamlessly integrated all these roles for his students’ benefit. To learn constitutional law from Larry was to inhabit what he called in one Harvard Law Review article “the curvature of constitutional space,” a place where the architecture of our founding document is a three-dimensional set of relationships, commitments and tacit postulates that can bend toward a better future.

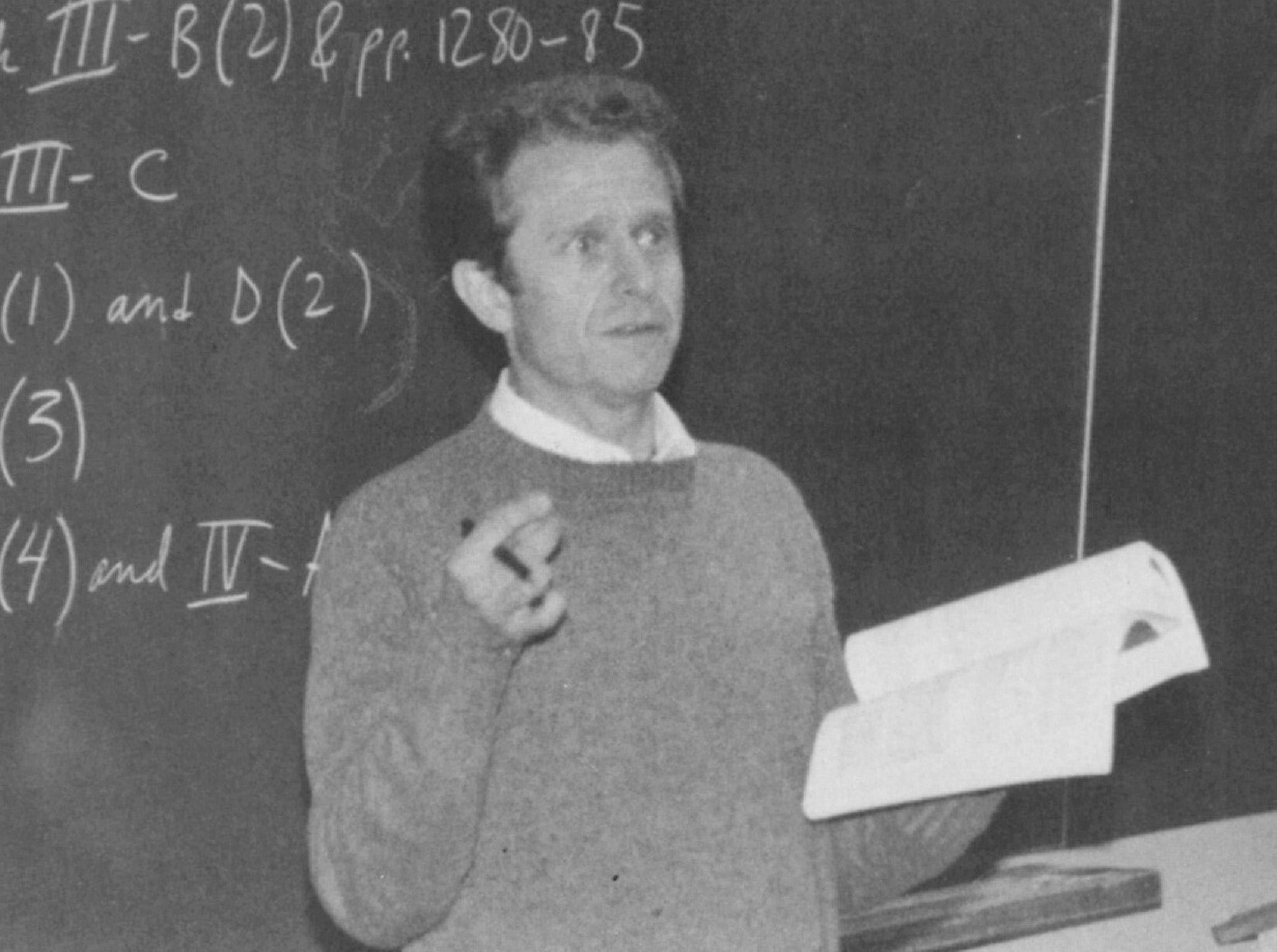

I first met Larry when I walked into Constitutional Law in Austin North as a 2L in 1979, marveling that the course lottery had awarded me a magical place in his perpetually oversubscribed class. He was mesmerizing. He spoke in full paragraphs, each sentence both precise and musical. His imagery was vivid: A constitution was a pre-commitment against future temptation, like Odysseus tying himself to the mast. He made Marbury v. Madison riveting. As he did case after case for the rest of the semester.

What 2L could ever forget his chalkboard drawing of reserved state powers as “islands in the stream of commerce,” complete with waves and palm trees?

Larry had then just published his magisterial treatise, “American Constitutional Law,” a brilliant interpretation of our nation’s constitutional jurisprudence that has been cited so often that Dean Erwin Griswold once said that “no book, and no lawyer not on the Court, has ever had a greater influence on the development of American constitutional law.” The treatise also influenced countless constitutional courts around the world and helped give Larry a Madisonian influence on the newly drafted constitutions of nations like South Africa and the Czech Republic.

Larry was then shortly to argue his first of 35 cases in the U.S. Supreme Court—Richmond Newspapers Inc. v. Virginia, where he secured a right of public access to court proceedings. He has since applied his exceptional gifts as an advocate to an astonishing range of high court cases. He pioneered gay rights before there was anything called gay rights, arguing for the right not to be fired or rousted from one’s private bedroom on account of sexual orientation. He has made the constitutional case for tort plaintiffs to receive punitive damages and terminally ill patients to control the circumstances of their deaths. At the same time, he has defended the powers of state and local governments to take property, enforce rent control, and impose nuclear moratoriums.

As he was becoming a premier Supreme Court advocate, Larry was also becoming a sought-after witness before Congress in committee hearings on constitutional subjects. He went on to provide such frequent and powerful congressional testimony, each a noteworthy work of scholarship in its own right, that I once heard Sen. Edward Kennedy call him “the 101st senator.” His telegenic appearances on national television amplified such commentary for a broader public, giving the nation far beyond HLS classrooms the privilege of hearing Larry crystallize the most fraught and complex constitutional topics in the most pellucid and persuasive form.

Laurence Tribe joined the HLS faculty in 1968.

For all this time on the national stage in such visible and influential roles, Larry’s first love beyond his beloved family always remained his students. Decade after decade, he prepared each class anew. He made even a large class an intimate conversation. His early passions, long before he became a national debate champion and legal scholar, were art and mathematics. No surprise, then, that he took with him to the lectern (as to the Supreme Court podium) elaborate multicolored notes full of geometric designs and arresting visual images. What 2L could ever forget his chalkboard drawing of reserved state powers as “islands in the stream of commerce,” complete with waves and palm trees? Or his illustration of the state action requirement as little governments waving the “arms of the state”?

Beyond all these gifts of analytical rigor and public eloquence, Larry also exemplifies profoundly the qualities of empathy, humanity, and love. He beams with pride at his former students’ accomplishments. He experiences others’ needs and wants as if they were his own. His optimism is contagious. He never gives up. And he always adapts. The man who typed his treatise on a dozen adjacent typewriters because he was not sure how to change the ribbon is now a widely followed presence on Twitter.

For all these reasons, it is difficult to imagine Harvard Law School without Larry still teaching there. The gift of his teaching was the foundation of my own career in academia and advocacy, as it was for so many others lucky enough to have been his students. And yet Larry is still teaching, through the thousands of students he has taught—professors and presidents, justices and jurists, advocates and artists, legislators and leaders, all of whom he has helped to understand our deepest traditions while seeing around corners to a better future.

Kathleen M. Sullivan ’81 is a partner at Quinn Emanuel Urquhart & Sullivan and was formerly a professor at Harvard Law School and dean of Stanford Law School, where she had also been a professor.