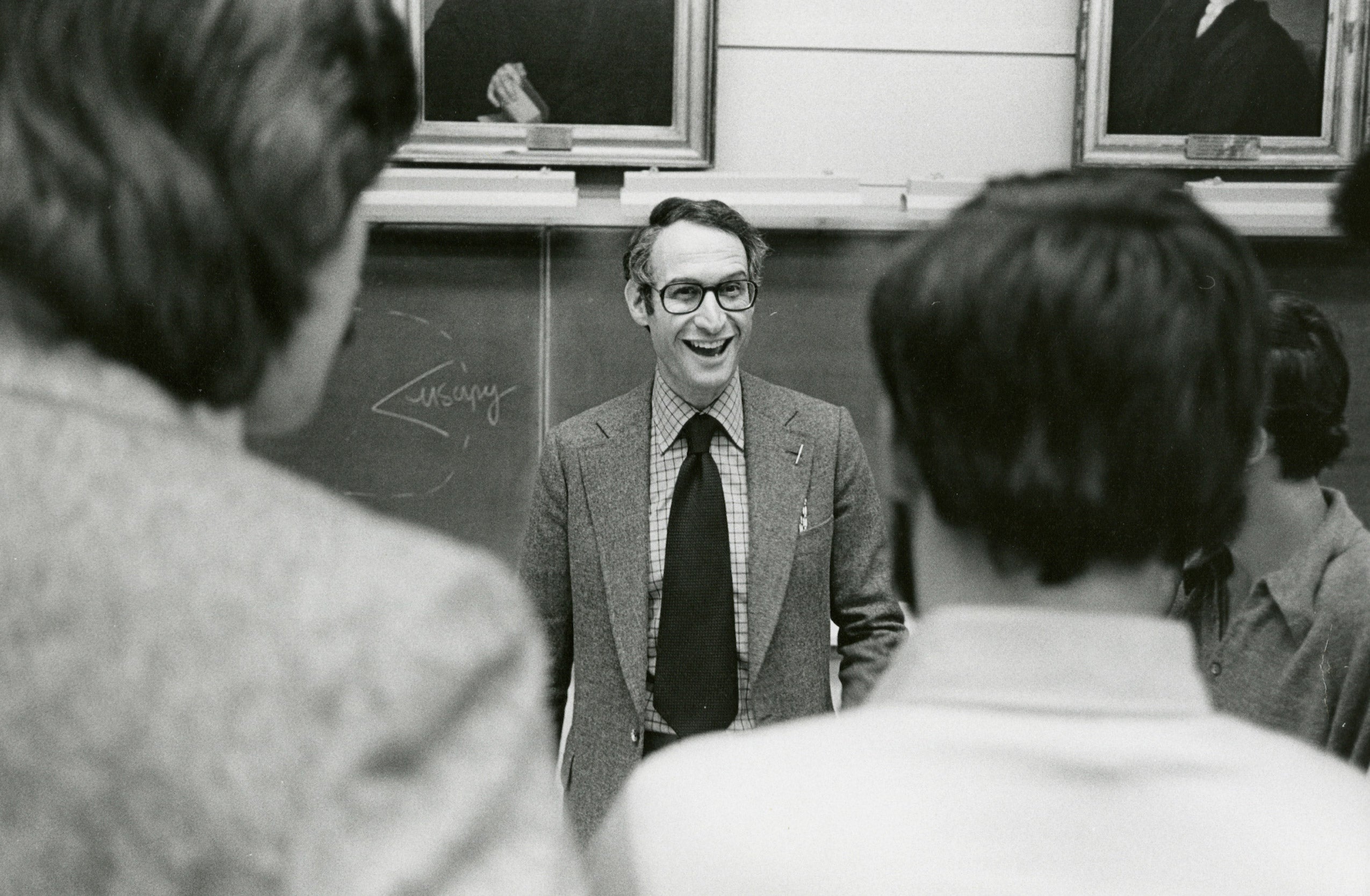

In a surprise tribute, dozens of Harvard Law faculty and former students crowded into a classroom on November 28 to honor legendary professor Charles Fried as he taught his last class after more than six decades at Harvard Law School. Dean John F. Manning ’85 thanked Fried for his intellectual leadership and influence on thousands of Harvard Law students.

Fried, visibly moved, expressed how much he enjoyed teaching and thanked his colleagues for their support and then, with characteristic humility and wit, added: “As nice as this has been, I did prepare a lesson for today that I do intend on teaching.”

Charles Fried, a consummate professor, renowned legal philosopher, and beloved colleague, died on Jan. 23 at his home in Cambridge. He was 88.

“Those who knew him well will not soon forget Charles’ unfailing kindness, generosity, brilliance, wisdom, warmth, and wit. Words cannot express how integral Charles has been to our Harvard Law School community, as a teacher, a scholar, an interlocutor, an institutional contributor, a mentor, and a dear friend to so many of us,” said Manning, the Morgan and Helen Chu Dean and Professor of Law at Harvard Law School. “Charles was a great lawyer, who brought the discipline of philosophy to bear on the hardest legal problems, while always keeping in view that law must do the important work of ordering our society and structuring the way we solve problems and make progress in a constitutional democracy.”

The Beneficial Professor of Law, Fried first joined the Harvard Law School faculty as an assistant professor in 1961. Apart from four years of service as solicitor general of the United States and another four years as an associate justice of the Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts, his intellectual home and life was at Harvard Law School.

Justice Stephen Breyer ’64, currently the Byrne Professor of Administrative Law and Process at Harvard Law School, was a student in the first class Fried taught at the law school and described Fried as a scholar who loved ideas. “He was ebullient. He had a good sense of humor. From the time I was a student in his first class here (Criminal Law, 1961) until today (I attended his last class a few weeks ago), I was fully aware that he loved teaching, and helping, both his colleagues and his students. … The Harvard Law School will much regret the loss of one of its ‘pillars.’”

Cass Sunstein ’78, the Robert Walmsley University Professor at Harvard, said: “Charles was a brilliant scholar, of course, and like the best athletes, he made everyone around him better. He was also the kindest and gentlest soul — and he made everyone around him kinder and gentler, too. Let’s remember that, and also his sense of mischief and delight, which makes me smile on a day of grief.”

Fried’s wide-ranging scholarly and teaching interests drew on connections between normative theory and the concrete institutions of public and private law.

He became nationally prominent when President Ronald Reagan nominated him as the 38th solicitor general of the United States. Fried served as solicitor general from 1985 to 1989, having previously served as deputy solicitor general. During his time in the Solicitor General’s Office, he represented the Reagan administration in 25 cases before the Supreme Court.

In 1995, Massachusetts Gov. William Weld ’70, a former student who served with Fried in the Reagan administration, nominated him as associate justice of the Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts, where he served until 1999.

Fried’s government service also included a year as special assistant to the attorney general of the United States, from 1984 to 1985, and advisory roles with the Department of Transportation, from 1981 to 1983, and the Executive Office of the President, in 1982.

News of his passing inspired an outpouring of praise and gratitude from colleagues and former students. Annette Gordon-Reed ’84, the Carl M. Loeb University Professor at Harvard, described Fried as “one of the kindest and most charming people I’ve ever met.” In a tribute in the Harvard Crimson, Professor Laurence Tribe ’66, the Carl M. Loeb University Professor Emeritus, said Fried was “one of a kind: a towering intellect, erudite beyond belief, invariably kind, and unfailingly decent.” And David B. Wilkins ’80, the Lester Kissel Professor of Law, said no one was more supportive of him than Fried when Wilkins first joined the Harvard Law faculty. “I have never known anyone who grew as much as a person and scholar — or pushed me to grow more,” Wilkins wrote. “We will not soon see his likes again, if ever.”

Fried’s staple courses in recent years were First Amendment and Contracts, but over the past six decades he also taught Commercial Law, Constitutional Law, Criminal Law, Federal Courts, Labor Law, Roman Law, Torts, and Appellate and Supreme Court Advocacy. With the aim of making contracts law accessible to a broader audience, Fried in 2015 built a highly successful HarvardX course called ContractsX, which used sophisticated online teaching approaches and methods to explain how the system of contracts helps order society.

During his time as a teacher, Fried argued several major cases in state and federal courts, most notably Daubert v. Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals, in which the U.S. Supreme Court established the standards for the use of expert and scientific evidence in federal courts.

A prolific writer, he reflected his myriad areas of expertise in scores of journal articles and numerous books. His books include “Anatomy of Values” (1970), “Right and Wrong” (1978), “Making Tort Law” (1980) (with David Rosenberg), “Contract as Promise” (1981), “Order & Law: Arguing the Reagan Revolution” (1991), “Saying What the Law Is: The Constitution in the Supreme Court” (2004), “Modern Liberty” (2006), and “Because It Is Wrong: Torture, Privacy and Presidential Power in the Age of Terror” (2011) (with Gregory Fried). At the time of his death, Fried was working on a book titled “Why I Changed My Mind,” which described why and how Mikhail Gorbachev, Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., and James Madison, had had changes of heart on important questions.

Born Karel Fried in Prague on April 15, 1935, Fried was the son of a senior vice president of the Skoda Works, an arms and automotive concern. He fled Czechoslovakia with his family, who were Jewish, in 1939 in advance of the Nazi invasion. Joseph Stalin’s rise to power in Russia and the fall of the Iron Curtain made it impossible for them to return. The family moved to New York in 1941, and Fried became a citizen of the United States in 1948, at the age of 13. In a 1990 Harvard Law Bulletin interview, Fried said, when the Communist government in Prague fell in 1989, he made up his mind “to do whatever I could to help Czechoslovakia’s ‘velvet revolution’ fulfill its promise to its people of liberty, dignity, and prosperity.” He was among several European and American lawyers, including Harvard Law Professor Laurence Tribe ’66, who advised the Czech government on its new constitution.

Fried earned his bachelor’s of arts degree in comparative literature and philosophy from Princeton University in 1956; a bachelor’s and master’s degree in law from Oxford University, in 1958 and 1960; and a J.D. from Columbia University School of Law, where he earned the Ordronaux Prize in Law at graduation. After law school, he served as law clerk to Supreme Court Associate Justice John Marshall Harlan II before joining the Harvard Law School faculty.

He is survived by his wife Anne (Summerscale) Fried, his son, Gregory, his daughter, Antonia, and his grandchildren.