In the quiet but anxious few weeks before the first wave of COVID-19 patients hit American hospitals, David Beck ’91 was working flat-out. The senior vice president and chief legal counsel at Boston Medical Center and his 10-member team were seeing the devastation in Italy and Spain. They knew they had to prepare their own hospital—a 514-bed academic medical center in Boston’s South End neighborhood—for a similar surge.

They knew, for example, that hospitals were scrambling to add as many beds as possible for COVID-19 patients, a task that required far more than clearing out space and setting up equipment. “The licensing of hospitals gets very specific about what you can use beds for and what equipment has to be available in certain rooms—regular medical rooms, surgical rooms, and rooms for children,” Beck explains. He and his team made sure that the hospital met the myriad regulations so it could significantly boost the number of patients it treated.

Initially, there were only a few sites across the country that were doing testing: “I had a couple of lawyers working practically 24 hours a day,” David Beck recalls. Within days, all COVID-19 testing could be done in-house.

Another hurdle: testing. Initially, there were only a few sites across the country that were doing testing, with a turnaround time of almost a week—a lag that was untenable at a moment that demanded speed. “I had a couple of lawyers working practically 24 hours a day with our lab staff, the FDA, and the Department of Public Health,” Beck recalls. Within days, they had gotten the center’s lab facilities licensed so that all COVID-19 testing could be done in-house.

He and his colleagues provided input to the state on honing extensive crisis standards of care to protect vulnerable populations. For example, the guidelines now spell out that health care workers forced to make tragically difficult decisions when resources become scarce, must not use characteristics such as socioeconomic status, incarceration status and immigration status to limit care.

Beck and his colleagues provided input to the state on honing extensive crisis standards of care to protect vulnerable populations.

As elective surgeries and other procedures got canceled, the team worked to develop a process to help hospital staff communicate those cancellations efficiently while maintaining rigorous standards of patient privacy.

These efforts began long before BMC had a single COVID-19 patient come through its doors. “We didn’t know what the outcome might be or how it might play out, so we were trying to think about every single thing that could happen and how to prepare for that,” Beck says.

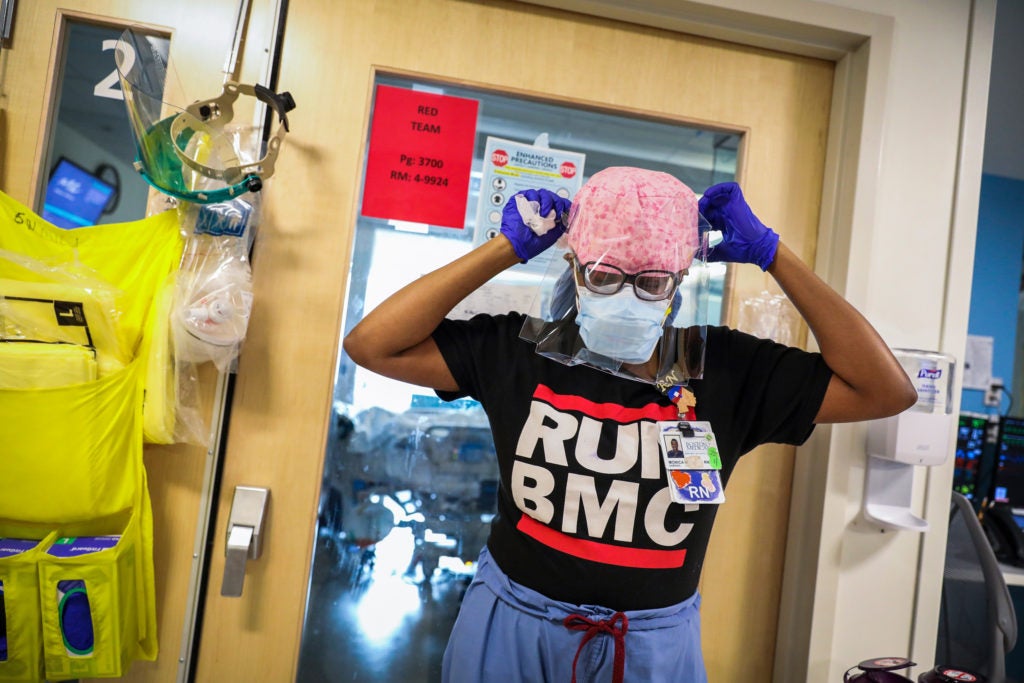

The preparation proved essential. For a short period in early April, every one of the 63 intensive care unit beds was filled. By mid-month, 70% of all admitted patients tested positive for the virus. In a feature story about the hard-hit facility, The Boston Globe called the hospital “the heart of the coronavirus storm.”

Beck and his colleagues had worked relentlessly with the hospital’s leadership team before the wave of COVID-19 patients arrived to ensure that patients would be well cared for and safe. They had solved critical problems early on and advised leadership and doctors in ways that would help the hospital navigate successfully through the peak.

In what is likely to become an inflection point for hospitals and health care nationwide, David Beck and his team are bringing not just extensive expertise to the challenges that lie ahead, but heart and humanity as well.

A challenge unlike others

While some of the work that Beck and his team were doing mirrored what was happening at other hospitals, the center also faced unique challenges. Boston Medical Center is a safety-net hospital, providing care for some of the city’s most vulnerable patients. Its motto, “Exceptional care, without exception,” is deeply ingrained in the organization’s culture.

Beck’s team worked with three different agencies to navigate the complex regulatory issues involved in converting an old hospital building into respite care to give COVID-19 positive patients without homes a safe place to isolate themselves to prevent transmission of the virus.

This reality meant that Beck and his team tackled issues that many hospitals didn’t have on their radar. A significant percentage of BMC’s patients are homeless, for example, Beck’s team worked with three different agencies to navigate the complex regulatory issues involved in converting an old hospital building into a space for respite care. The facility gave COVID-19 positive patients without homes a safe place to isolate themselves to prevent transmission of the virus.

Many patients who come to the hospital work at low-wage jobs and live in Boston’s urban core, and a great number suffer from preexisting conditions such as diabetes and asthma. For a large proportion of patients, English is their second language. These are at-risk populations at any time; during the COVID-19 pandemic, the impact on these groups has been devastating. For some in health care, facing such challenges might feel disheartening. But for Beck, working at BMC feels closer to a calling.

Beck has long been immersed in the world of health care. His mother was a nurse, and his father was a lab technologist who managed a doctor’s clinic. After earning his degree from Harvard Law and working in private practice, Beck landed at the Massachusetts Attorney General’s Office in 1999. As part of his work, he was responsible for the oversight of public charities—a designation that most hospitals in Massachusetts hold. By the mid-2000s, as health care reform became a debate and later a reality in the state, Beck found himself working with hospitals and their boards as they navigated the changing environment.

In 2007, a former colleague who had landed at BMC asked him to come for a visit, and as he strolled through campus, he was immediately won over. “The mission, exceptional care without exception, [drove] everyone I talked to and everything about the hospital,” he recalls. “It was interesting to me to think about a focused part of the law.” He soon joined BMC as deputy general counsel.

The hospital has been at the forefront of both recognizing and addressing social determinants of health that can lead to significant differences in health outcomes among individuals—things such as education level, income, discrimination, and living situations. BMC aims to improve outcomes for its patients through its wide-ranging care. For example, it has a therapeutic food pantry that allows doctors to give “prescriptions” for specific diets that patients may need to follow for their health. It also founded the Medical-Legal Partnership, an organization now independent of the hospital, which provides legal assistance to patients. The partnership tackles issues such as helping to make sure that housing difficulties or other challenges don’t get in the way of patients receiving the care they need. “One of the things I like about being here is being able to look at the ways that we can support our patients beyond just their medical care,” says Beck.

In his pre-pandemic role, he and his team had a range of responsibilities. They worked with the hospital’s board of trustees and senior leadership to oversee the hospital, they drafted and reviewed contracts, and they oversaw litigation. They also provided direct advice to physicians on patient care issues—how to address consent if a patient is incapacitated, for instance. “We advise them on the legal ground rules,” Beck says. The coronavirus layered in many new responsibilities.

Once COVID-19 hit Boston, the hospital was under intense pressure for weeks. This included a few hours on April 4 when a number of patients had to be transferred to other hospitals across the city because BMC’s intensive care units were full. Still, the hospital was able to steer through the worst of the crisis successfully, thanks in no small part to the advance planning and advice from Beck and his team.

Martha Samuelson ’79, chair of Boston Medical Center’s board, says that Beck has been the exact right person for the role in this difficult time. “David is fearless. He’s comfortable pushing back on anyone when he doesn’t think something is a good idea. He never ups the anxiety level in a complex interaction and he’s solutions-oriented,” she says. “The complexity of running the legal operations in a highly regulated organization means there are so many different constituents and so many boxes to check off. David is pitch perfect with all of them.”

Today, even with the peak well past, Beck and his team continue to work closely with BMC’s research operations staff and faculty at the hospital who are proposing studies and projects linked to the virus. “We want to make sure we can get the proposals through the process and that we have the right protections in place for patients and employees,” he says.

A virus that will transform health care

Working in a hospital setting, Beck is no stranger to illness. But he admits that this virus feels significantly different. “I’ve seen what this disease can do to our patients—how quickly it can spread and how quickly it can develop into very serious conditions,” he says. He thinks about his friends and family constantly. He has family in Tennessee and his husband has family in Michigan, and he frets about not being close to them. “I have this never-ending worry in the back of my mind about them,” he admits.

He thinks, too, about all of the ways his office must be transformed once it’s deemed safer for more people to come to work. How will they make sure that staff can stay safe if they take public transportation to work? What will be the best practices for physical distancing in an office environment? How can workers rotate their work schedules and prevent crowded conference rooms? For patients, the hospital is making myriad changes to elevators, waiting rooms and exam rooms.

But even with all of these changes on the horizon, Beck sees true opportunities emerging from this difficult time.

Telehealth, which had made only slow inroads into health care over the years, has skyrocketed during the pandemic. It offers enormous opportunities to those who live far from a hospital or might otherwise struggle to get to one. It is likely to take a stronger hold, he thinks, even after the pandemic subsides.

Meanwhile, the center’s pediatrics department has taken a van out to nearby neighborhoods to give vaccinations to kids so they don’t miss them. He loves seeing this type of innovation and growth, and hopes he can help strengthen the infrastructure in ways that make more of these ideas realities. “Are there ways we can build on that, to do more out in the community?” he asks. “It’s more convenient for our patients, it helps them get their health care, and it keeps people from congregating, which we worry about greatly these days.”

These are the kinds of issues that Beck is hungry to tackle. When a field like health care gets upended at a moment like this, what becomes possible? “There are so many things that are difficult about the way we provide health care now, and this is forcing us to think about how we do that. It’s a fascinating challenge. There’s plenty of opportunity for all of us to think differently about health care and the oversight of health care.”