IP curriculum evolves with student interest and new technologies

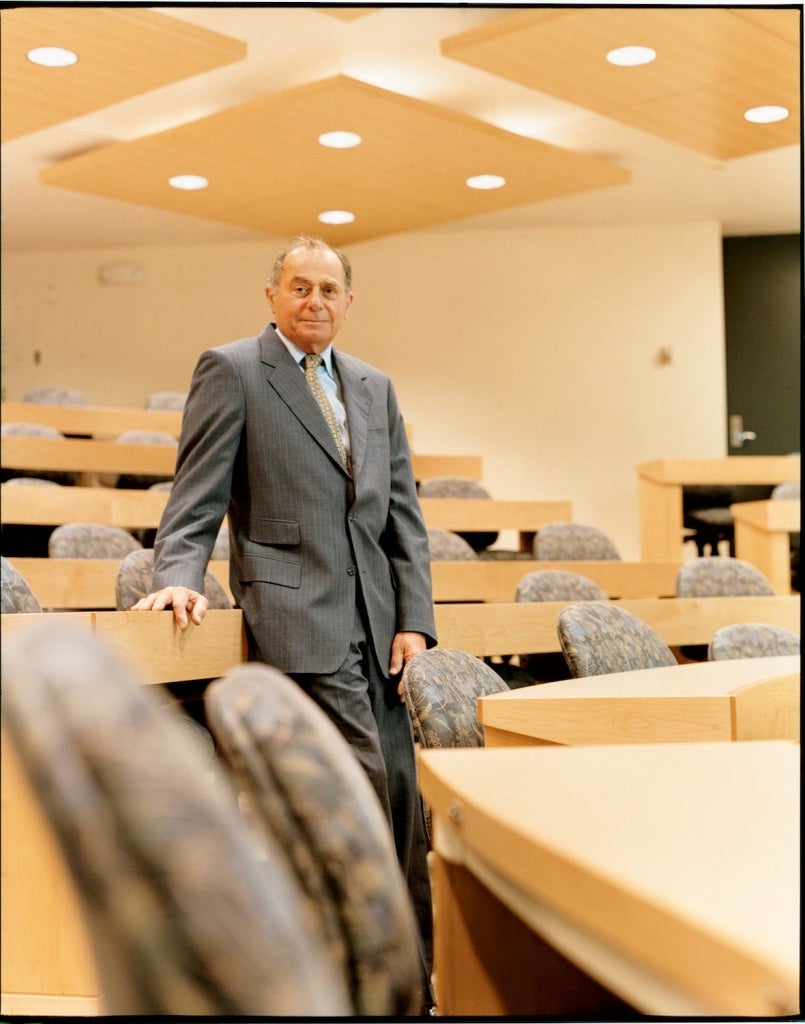

Walk by Professor Lloyd Weinreb’s copyright lecture, and you might hear the songs of Rolling Stone Mick Jagger, former Beatle George Harrison or even pop singer Michael Bolton blaring from the classroom.

No, they aren’t favorite tunes from Weinreb’s record collection; he much prefers classical composers or Rodgers and Hammerstein show tunes.

But each of these musicians was involved in a prominent copyright infringement suit, and Weinreb plays their songs as he discusses their cases. On another day, Weinreb might display the insignia of the National Football League’s Baltimore Ravens, the subject of another copyright dispute.

Such multimedia presentations were certainly not the norm when Weinreb ’62 took Copyright with Benjamin Kaplan at Harvard Law 42 years ago. But much has changed in the intervening decades in how students learn about intellectual property here.

Whereas Kaplan’s two-hours-per-week copyright law class was the only intellectual property course offering then, students today can fill whole semesters with the school’s nine IP-related offerings, including recent interdisciplinary additions such as cyberlaw and biotechnology law. Just this fall, the school received a $3 million gift to establish its first professorship in patent law.

“The demand for intellectual property has been immense,” says Weinreb. “The whole world is interested in intellectual property right now.”

Outside of class, students with an interest in IP can do research or enroll in a clinical at the Berkman Center for Internet & Society. Or they might write articles for the student-run Harvard Journal of Law & Technology or help organize conferences for the Harvard Committee on Sports & Entertainment Law.

Though the Internet bubble burst years ago, those offerings keep attracting more students. One explanation: Harvard Law’s current student body is stacked with Internet startup survivors who brought their interest in technology with them. But student interest in IP extends far beyond those Silicon Valley expatriates. To see why the same issues are relevant to the average HLS student, look no further than Weinreb’s copyright class this past spring that met three times each week in Pound Hall.

The first sound a visitor hears is the constant tapping of keys–nearly all of the students in the room are typing their notes on a laptop. And, thanks to schoolwide wireless Internet access installed this academic year at the direction of Dean Elena Kagan ’86, the World Wide Web is just a click away at every seat. That innovation is of little interest to Weinreb, a self-described “semi-Luddite,” who didn’t even have a computer in his office until 2001. Even today, he says, he doesn’t know how to do much besides e-mail and hasn’t ever looked at file-swapping programs like Napster.

Still, in the 16 years since he started teaching copyright, Weinreb’s approach has evolved along with new technologies. In today’s lecture, he is wrapping up the copyright portion of his class with a lecture on the fair-use doctrine before starting a half-semester overview of patent law and trademarks.

At the same time, Professor William Fisher III ’82, co-director of the Berkman Center, is leading a class discussion in his patent law course while standing before a PowerPoint presentation. Yet the class discussion topic is considerably less high-tech: a hypothetical salt-injected fishing lure designed to catch bass.

He presses one student to discuss whether the inventor should get a patent and what the appropriate field of art should be. During his second IP class of the day, later that night, Fisher takes a back seat to his students in a seminar on current trends in cyberlaw.

Eating takeout Thai food around a table in the attic of Austin Hall, Fisher and his 15 students talk with visiting UCLA law school Professor Jerry Kang ’93 about who should own rights to private information on the Web. Kang asks them to consider, if personal data like online buying habits is considered property, whether it’s best controlled by individuals, by companies or in some form of mutual control.

In some classes, such as cyberlaw or biotechnology law, IP may be only a part of a broader interdisciplinary course. The biotechnology class is co-taught by Professor Charles Nesson ’63 and two practitioners, including Boston biotech attorney Bruce Leicher.

Leicher says he tried to impress upon the 36 students in the class how central a role intellectual property rights play in biotechnology innovation. “Until you have intellectual property, you have no research and development to sell,” explains Leicher, who currently serves as vice president and chief counsel at a biotech firm.

In one class, students split into teams and negotiated a hypothetical agreement between a university and a biotech firm to obtain rights to a critical protein for a pharmaceutical development.

“I’ve learned a lot from these classes,” says 3L Chris Carnaval, who took the biotechnology course last fall. He’s also enrolled in other IP courses, including Copyright and Internet & Society, and worked both summers during law school at IP law firms. One summer associate project: defending a suit against the Washington Redskins National Football League team trademark, which plaintiffs argued disparaged Native Americans. “I wish the law school offered more classes like this,” he says. “I’d definitely take as many as I could.”

In the future, Weinreb envisions the school expanding IP course offerings further to include a regular course in trademark and unfair competition, a patent course every year and perhaps a separate patent litigation course. Such offerings draw disproportionately on students with scientific or technical backgrounds who are looking for ways to incorporate those interests into a legal career. Others earned undergraduate degrees or Ph.D.s in computer science or other high-tech disciplines.

Some worked at Internet startups–or, in the case of 3L Lara Garner, designed precision equipment for the PC board industry before studying philosophy in college. Still others come from creative fields like art, music or writing.

“It seemed like a natural fit,” says Renny Hwang, a 2L who came to HLS after working as a product manager at an Internet startup. 3L Michael Joffre came to HLS after completing a Ph.D. in astrophysics at the University of Chicago and working for a year looking at gigantic clusters of galaxies with telescopes.

Joffre, who will clerk at the federal circuit court that handles patent cases after graduating this year, says his background provides a unique perspective on the law. “It’s slightly more methodical, slightly more analytical,” he says. “It’s just part of the training you receive as a scientist.” He says he found it easier during his two summers at IP firms for him to relate to inventors and creators. “You have a similar background,” he says.

1L Jeff Engerman worked at Internet search engine Northern Light, doing operations and product management work, before enrolling at Harvard Law. He barely arrived before finding a way to learn about IP. Engerman has started doing research at the Berkman Center’s “Chilling Effects” project, which supports free speech on the Internet through a Web site that helps Internet users respond to legal threats such as cease-and-desist letters.

In his first semester, Engerman analyzed letters posted on the Chilling Effects site. In the spring semester, he switched to analyzing trends in cease-and-desist letters. Though the research isn’t done yet, Engerman says there are many legitimate enforcement actions. This summer, he’ll continue his research as an associate at the Berkman Center.

Engerman says such work has already changed how he thinks about IP. “Working in the field, you start to feel it’s predetermined that larger players will take over,” he says. “But getting into the legal way of thinking, you start to understand there are more options to effectively fight for intellectual property rights and support the progressive goals of the Internet community.”

There are also IP research opportunities that attract foreign students. LL.M. student Yuanshi Bu of China helped file copyright registrations and translate documents for the Chinese version of the International Commons project. The “I-Commons” is designed to help automate the process by which users can obtain permission from authors for online content. Bu, who previously studied IP law in Europe and helped clients in China enforce IP rights against counterfeiting factories, says learning such practical skills was “quite helpful.”

Each semester, half a dozen students also get practical experience by enrolling in the Berkman Center’s clinical program, which was the first of its kind when created in 1999. “We give students the opportunity to learn that, yeah, that looks good on paper, but you see what will happen in the real world and find all the loopholes,” says Diane Cabell, the Berkman Center’s director of clinical programs.

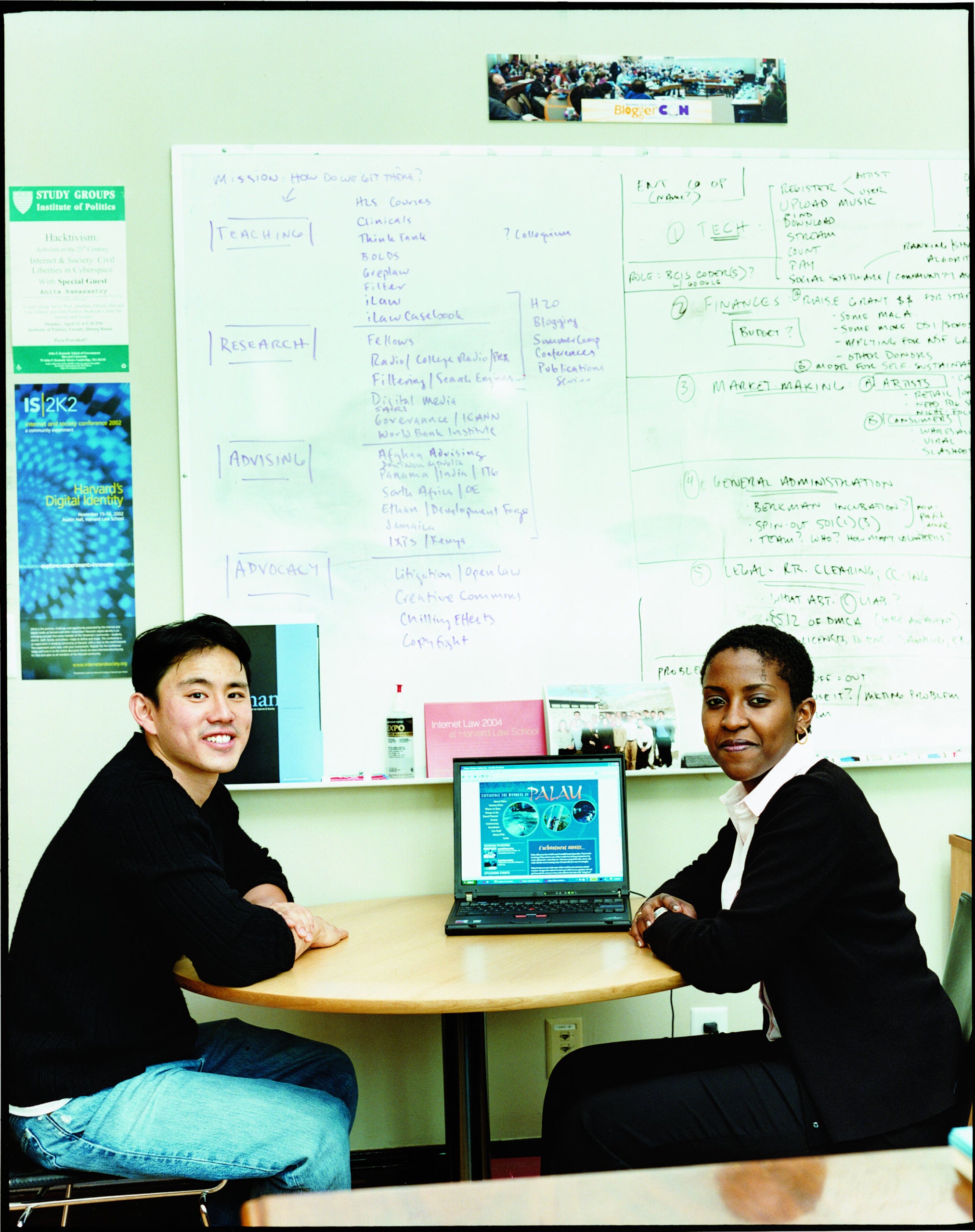

For Hwang, his clinical meant learning where in the world is the island of Palau. That’s because Hwang was assigned to help draft laws governing domain name registration and resolution for the South Pacific island nation two hours from Guam, which is just two and a half times the size of Washington, D.C. Making matters more interesting: Palau requested a pro-domain holder policy, unlike other nations, which tend to favor the trademark holder.

Hwang and his partner on the project, 2L Ory Okolloh, say building a domain name policy from scratch was a great experience–though the 12-hour time difference with their clients meant e-mails were the only way to reach them.

By the end of the term, Okolloh and Hwang expected to have submitted a draft policy. “We can point to something that’s tangible,” says Okolloh, who will work this year as a summer associate at a Washington, D.C., law firm with an IP practice.

And, for students who want to fill their free nights and weekends with IP too, there are always plenty of student activities to join. Pick up any recent copy of the Harvard Journal of Law & Technology and read student-written notes with titles such as “Trespass to Chattels and the Internet” and “Control of the Aftermarket Through Copyright.”

In March, JOLT hosted its annual conference on the impact of emerging distribution technologies, featuring panelists such as Shari Steele, executive director of the Electronic Frontier Foundation, and TiVo’s general counsel, Matthew Zinn. One week earlier, the Harvard Committee on Sports & Entertainment Law hosted its own conference that featured EFF co-founder and former Grateful Dead lyricist John Perry Barlow. Unfortunately, many Committee on Sports & Entertainment Law members couldn’t make the JOLT conference–not that they weren’t interested in the topic. It’s just that they’d flown to Texas for a music industry trade show.