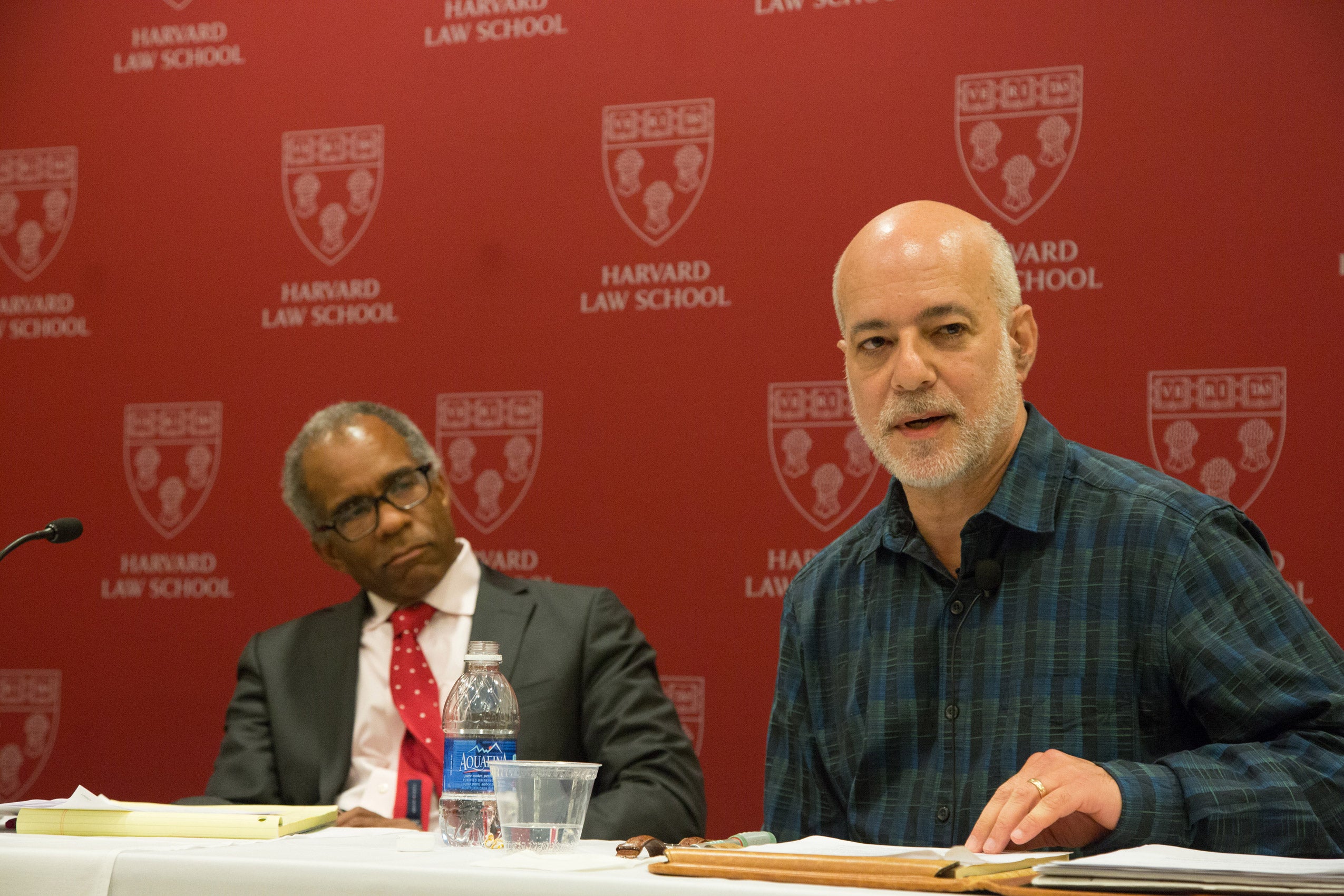

In a panel discussion at Harvard Law School in October commemorating the 50th anniversary of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Professor Kenneth W. Mack, characterized the legislation as the culmination of decades of struggle for racial equality by African-American activists and organizations. But he also pointed out that it stemmed from the growth of federalist thinking starting in the 1930s with the New Deal and direct federal involvement in job creation.

“The New Deal was incredibly racially discriminatory, and civil-rights activists began to think about the power of the federal government to regulate employment discrimination in a sustained way,” he said.

The result, he pointed out, was that the debate leading up to the legislation focused largely on the question of whether Congress had the right to enact such a statute. “At the beginning of the New Deal, the answer would have been basically no. But by ’64 the answer was: maybe yes. And civil-rights activists were part of that story.”

A series of events, culminating in the 1963 March on Washington and Dr. Martin Luther King’s historic “I have a dream” speech, galvanized public opinion. But as Professor Randall Kennedy pointed out, the nation’s lawmakers were still reticent about taking on anti-discrimination per se.

“The primary justification for [the Act] was the Commerce Clause of the federal Constitution—the idea that racial discrimination imposes a burden on the economy,” he said. “So even though Congress was trying to do right, trying to push some degree of racial decency in our society, they couldn’t be completely candid and straightforward about what they were doing.”

From the beginning, calls for collective civil rights have run up against the right of expressive association—assertions by individuals and groups that they have the right to discriminate in order to achieve their goals. Prior to the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Kennedy said, civil-rights activists had failed to successfully challenge that aassertion in arguing that they had a right to be served at lunch counters or in stores.

In crafting the Civil Rights Act, Congress responded to that conflict with Article II, which prohibits discrimination against protected groups in businesses or other places that are considered “public accommodations.”

However, recent challenges involving claims of expressive association—including one by the Hobby Lobby arts-and-crafts store chain, which won a U.S. Supreme Court victory June 30 when the Court ruled that businesses have a right to exemption from federal laws that conflict with their owners’ religious beliefs—have thrust Article II back into the realm of public debate.

In his remarks, Professor Mark Tushnet noted that the Court has ruled that Boy Scouts of America and the Boston St. Patrick’s Day march organizers have expressive-association rights to exclude gays and LGBT organizations because they are public entities not bound by Article II and that “the Hobby Lobby decision of the last term places the commercial/noncommercial distinction under pressure.”

One of the results, he said, has been new libertarian thinking about the conflict between civil-rights protections and rights of expressive association. Prior to enactment of the Civil Rights Act, he said, the laws in many southern states effectively created “monopolies,” which prevented “unwilling discriminators” from serving African-Americans. The Civil Rights Act broke that monopoly to create competitive markets.

“Therefore, the libertarian would conclude, the underlying principle of choosing the people you want to transact with re-emerges as the governing rule,” Tushnet said, “and so in a market that has become competitive because of the Civil Rights Act and because of social change of various sorts, they would say there’s no need for a statutory prohibition on discrimination.”

Professor Joseph Singer, who organized the panel, also took a contemporary view of the Civil Rights Act’s current role by noting its limitations. While Title II says that protected groups have the right to engage in commerce in places of public accommodation, he said, it doesn’t address the treatment to which a customer might be subjected.

“No federal statute prohibits racially discriminatory treatment while you’re in the store,” he said. “I think it’s important to note that there remains discrimination in places of public accommodation in the United States and there’s actually quite a lot of it.”

Mack agreed.

“There’s this idea that we’re in a world where civil-rights statutes are no longer necessary,” he said. “I think it’s really up to all of us to make the claim that although we’re not living in 1964, where discrimination is alive and well in the present, there’s still room for civil-rights laws.”