“Talking to terrorists is different from giving in to them. Sometimes it may be good practice to know what they are thinking, or, as a line in ‘The Godfather’ goes, it is important to ‘keep your friends close but your enemies closer.’ FBI and police hostage negotiators nearly always negotiate with hostage-takers–to gather information, to look for leverage and in an effort to gain the psychological advantage.”

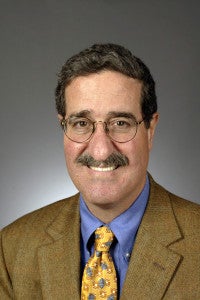

Professor Robert H. Mnookin ’68, in a Sept. 26 op-ed in the Los Angeles Times, written with Susan Hackley, managing director of the Program on Negotiation, on negotiating with terrorists and hostage-takers.

* * *

“Conservatives need to wake up and smell the coffee. Judges, including conservative ones, do make law from the bench. We should see to it that they make good law rather than the bad kind. The first step toward that goal is to require that they admit what they’re doing. Transparency is a virtue, in judging as in governing more generally. American courts are too shrouded in mystery already; they would benefit from more sunlight, not less.”

Professor William J. Stuntz, in a Jan. 11 op-ed in the online journal Tech Central Station, criticizing right-wing legal theory as not being truly conservative.

* * *

“Of the 18 former directors who were defendants in the Enron case, only 10 have to pay under the settlement. More important, according to the complaint against them, these 10 sold Enron shares worth more than $250 million during the period in which Enron was misreporting its financial affairs. According to the lawyer for the lead plaintiffs, the settlement requires each of these 10 to pay an amount equal to 10 percent of his or her pretax profits. They will be able to keep the other 90 percent–which amounts to $117 million–while investors who held their Enron stock lost their shirts.”

Professor Lucian Bebchuk LL.M. ’80 S.J.D. ’84, in a Jan. 17 op-ed in The New York Times, criticizing the legal and financial settlement of an Enron civil suit.

* * *

“Compromises are inevitable on a multi-justice court, but they should be clearly articulated and easily understood by the public, or at least by the legal profession. This decision, and many others over the past decade, can be explained only by means of patchwork pragmatism, vote-swapping and other considerations inappropriate for high court decision-making.

“Ours is the most powerful Supreme Court on Earth. Its job is to interpret the Constitution by reference to principle and precedent. If it cannot explain and justify its decisions, it will deservedly lose much of its authority.”

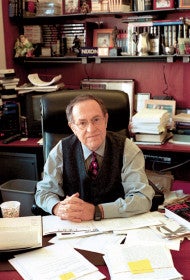

Professor Alan Dershowitz, in a Jan. 17 op-ed in the Los Angeles Times, criticizing the U.S. Supreme Court for reaching a seemingly contradictory two-part decision on sentencing guidelines.

* * *

“The United States has never opposed ICC [International Criminal Court] prosecutions across the board. Rather, it has maintained that ICC prosecutions of non-treaty parties would be politically accountable and thus legitimate if they received the imprimatur of the Security Council. The Darfur case allows the United States to argue that Security Council referrals are the only valid route to ICC prosecutions and that countries that are not parties to the ICC (such as the United States) remain immune from ICC control in the absence of such a referral.

“This course of action would signal U.S. support not only for the United Nations but for international human rights as well, at a time when Washington is perceived by some as opposing both.”

Professor Jack L. Goldsmith, in a Jan. 24 op-ed in The Washington Post, suggesting that the Bush administration’s opposition to the International Criminal Court should not stop the administration from backing a U.N. Security Council referral to investigate human rights abuses in the Sudan.