Winnie the Pooh, Piglet, Christopher Robin, an early version of Mickey Mouse. What do these iconic Disney characters have to do with one another, aside from being beloved by millions of children around the world?

They are all now, or will be soon, in the public domain.

October 16 marks 100 years since Walt and Roy Disney founded Disney Brothers Studio — an animation company that would go on to produce some of the most cherished cartoons and films of the next century, spawning twelve theme parks, countless toys, clothing, and other merchandise, and a conglomerate worth $145 billion.

In addition to decades of entertaining kids and adults alike, Disney has also been known as a fierce defender of its intellectual property rights, filing many lawsuits against companies and individuals for copyright and trademark violations over the years. In 1989, for instance, the company even threatened to sue three Florida daycare centers unless they removed murals featuring some of its characters.

Disney, along with other companies with a strong interest in protecting IP, has also long lobbied for federal legislation to prolong copyright protection. The most recent extension, 1998’s Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act (sometimes derisively called the Mickey Mouse Protection Act), lengthened copyright for new works and extended the renewal term for those published before 1978.

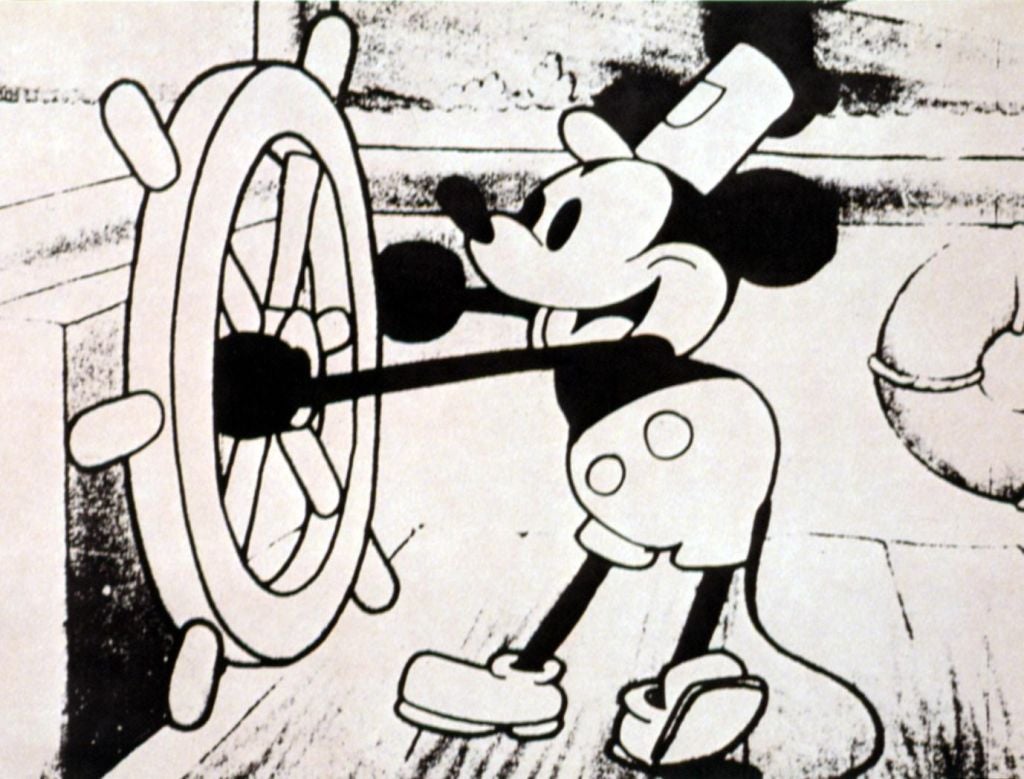

Despite these efforts, characters like those from A.A. Milne’s Winnie-the-Pooh series and Steamboat Willie (a precursor to Mickey Mouse) have begun entering the public domain or will do so soon – and are already being used by new creators in sometimes controversial ways.

As Disney and its diehard fans mark the company’s centennial, Rebecca Tushnet, the Frank Stanton Professor of the First Amendment at Harvard Law School, spoke with Harvard Law Today about how the company has influenced copyright law in the U.S. and how creators can use works now in the public domain – if they proceed cautiously.

Harvard Law Today: How much influence has Disney had on copyright law over the last century? Has its impact been exaggerated by critics?

Rebecca Tushnet: This is a complicated question. Disney has preferred to do its work through trade organizations in general, rather than putting itself out there on the front lines. I think this is because all the large content owners know that they’re much more sympathetic when they put forward individual artists making claims for longer, more extensive copyrights.

HLT: Many of Disney’s most well-known stories and characters — like Cinderella or The Little Mermaid — are themselves derived from older fairy tales. Does Disney own the copyright to any elements of those films and characters?

Tushnet: Disney owns the copyright in whatever expression it contributed. So, that means its particular version of the story, including the visuals, and any surprising, non-standard plot elements. Although, with a lot of these stories, there are lots of variations. Anyone can do their own version of these stories — including something like “Cinderella in space.” What Disney is likely to own is its visuals.

HLT: A few major Disney characters, such as Steamboat Willie and Winnie the Pooh, are now in the public domain, and others are expected to join them in the coming years. What does that mean?

Tushnet: The easiest possible answer is that anybody can definitely reproduce the works that are in the public domain. You can also make your own new derivative works, as long as you’re only using the public domain elements. I think, with the Winnie the Pooh horror movie, what you saw is them very much not using any visuals that were similar to things that are still under copyright, because some of the books were made later.

“It’s no accident that things go into the public domain. But the contours of that are as yet unclear, precisely because Congress lengthened the copyright term, and so we didn’t get this problem until recently.”

HLT: Despite being in the public domain, Winnie the Pooh and others remain protected under trademark law, so long as Disney continues to file the correct paperwork. What does trademark protection do, and how might it limit how others can use characters now in the public domain?

Tushnet: This is actually the most complicated issue, because in theory, now that they’re in the public domain, anybody can copy them. And yet, it is quite likely that Disney would sue you for putting an image from a public domain work on a lunchbox. Disney should probably lose that, but it’s going to fight very hard.

The Supreme Court, in a case called Dastar Corp. v. Twentieth Century Fox Film Corp., said, basically, when something’s copyright expires, other people get to use it, and to use it without attribution, as long as they aren’t misrepresenting the physical source of what they’re selling. But what that means in practice has not fully been worked out, because so few things have entered the public domain in the past 20 years.

I think people should be free to use the materials despite the existence of trademark rights, because trademark law shouldn’t be able to stop you from doing what copyright law allows you to do and is set up to allow you to do. It’s no accident that things go into the public domain. But the contours of that are as yet unclear, precisely because Congress lengthened the copyright term, and so we didn’t get this problem until recently.

HLT: The most recent copyright extension, called the Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act, made its way to the Supreme Court in 2003. What did the Court say in that case?

Tushnet: What the Court basically said is that when everybody agrees that the result is a limited term of copyright protection, it’s basically up to Congress to decide how long that term should be. And even if every economist agrees that it won’t get us more copyrighted works, it’s still rational for Congress to do it, at least if it thinks there might be some other benefit.

HLT: Do you think Disney and other companies will try to push for another extension of copyright protection?

Tushnet: It seems fairly unlikely, given that the backlash to the previous term extension brought together a bunch of groups for the first time who had never understood their interests to be linked. But nothing’s impossible. I will say that, as a big company, the works that are most valuable to you are the ones you just released this year. As if you’re releasing new iterations of a franchise, that seems to be the strategy that companies like Disney are using to enhance the value of their old stuff. So, it’s probably not worth the political capital required to extend the term again. It’s much more important to them to be able to make the next season of “Andor,” rather than to extend the term of copyright of a 1930 animation.

HLT: In your view, what is the appropriate balance between protecting intellectual property rights and the rights of new creators to build on those works?

Tushnet: Given that most of the profit comes in the first few years after a work’s publication, the copyright term is already way too long. In my ideal world, it would be much shorter, and then after a reasonable opportunity to exploit the copyright, the work would enter the public domain.

But even without that, if we have lots of freedom to react and to use works in the public domain without worrying about being sued for infringement, we can have a successfully functioning system. So, my ideal is to recognize creative freedom, including the freedom to make your own version of things in the public domain.

This conversation was edited for length and clarity.

Want to stay up to date with Harvard Law Today? Sign up for our weekly newsletter.