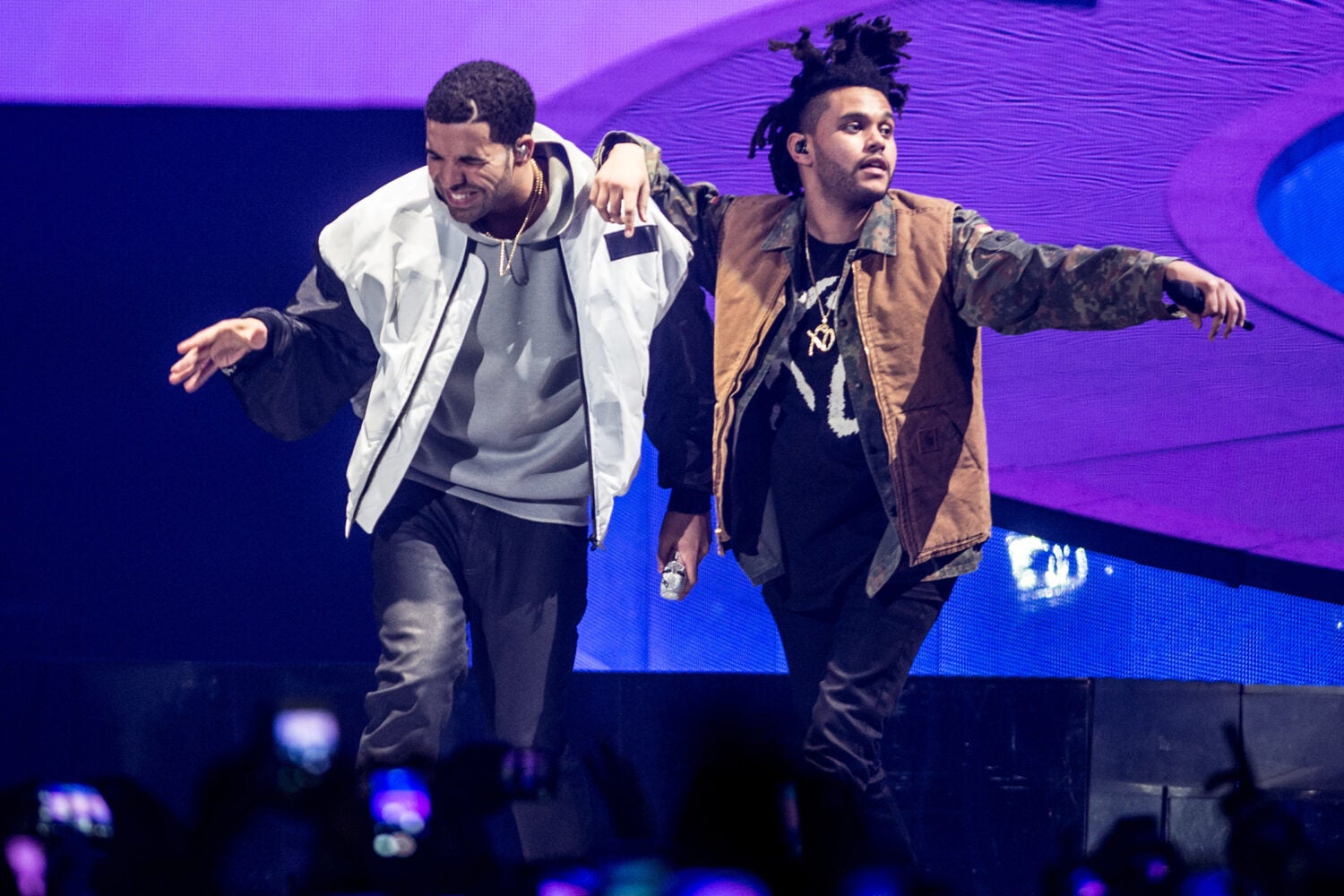

A few weeks ago, a new song purportedly by Drake and The Weeknd landed on TikTok and Spotify and quickly spread like wildfire across the internet. “Heart on My Sleeve” was met with rave reviews and a high degree of excitement among hip hop fans, not only because of the track’s infectious lyrics and melody, but because of a curious detail about the featured artists — in fact, they hadn’t made the song at all.

Instead, the tune had been created using artificial intelligence by TikTok user Ghostwriter977, who had trained AI on Drake and The Weeknd’s works and generated the new song, which impeccably mimicked the artists’ voices, lyrics, and musical styles. Within days, however, his video, which had gained over 9 million views, was removed from TikTok, Spotify, and other platforms in response to claims by the artists’ record label, Universal Music Group.

In the wake of the song’s takedown, questions about the kerfuffle remain. Did the track really violate Drake and The Weeknd’s copyright rights? What other avenues do the artists have to fight AI-generated music? And is the song eligible for copyright protection of its own? Harvard Law Today spoke with intellectual property expert Louis Tompros, a lecturer on law at Harvard and partner at WilmerHale, about these pressing questions — ones he says courts are only beginning to consider.

Harvard Law Today: What is the legal landscape right now related to AI-generated art?

Louis Tompros: In general, copyright law gives copyright owners the exclusive right to reproduce, distribute, perform, or display their works, and to create derivatives of those works. I think of the impact of AI on copyright in two categories. One is the rights that AI-generated material itself has, and the second is what rights someone might have that they can assert against AI-generated material.

On that first issue, the question is: Who, if anyone, owns the copyright to material that is in whole or in part generated by artificial intelligence. And there has been some incredibly helpful recent guidance from the Copyright Office on exactly this. On March 15, the Copyright Office issued its latest formal guidance, which reaffirmed its position that works that are created by AI without human intervention or human involvement cannot be copyrighted. The Constitution is what gives Congress the ability to enact copyright laws, and the Constitution uses the word “author.” The copyright statutes therefore use the word “author,” and “author” has been interpreted repeatedly to mean a human. So, only humans can be authors for purposes of the constitutional and statutory copyright grant.

Now, to be clear, that’s the Copyright Office’s position, but this hasn’t yet been tested fully in the courts, and it will be. But I should note that the Copyright Office also said that a work that contains AI-generated material may be copyrightable where there’s some sufficient human authorship; for example, if a human selects or arranges AI material in a creative way, that can still be protected by copyright.

HLT: And what about the second issue?

Tompros: The second big issue is, what rights do human copyright owners have when AI creates something? And here, there are two categories of questions — an input question and an output question. On the input side, does the training that is required to create these complex AI models implicate copyright? In other words, if I train an AI by having it listen to a whole bunch of music, have I infringed the copyright of the owners of that music if I did it without their consent? Or is that protected in some way by fair use or otherwise under the copyright statute?

Then there’s the output question, which is, if copyright law gives the owner the exclusive right to create a derivative work based on their own prior work, is creating something using AI based on that other work then a derivative work that only the original copyright owner would have the ability to make? In general, music in the style of someone else is not considered a derivative work for purposes of copyright law and is allowed. But where we have machine learning and AI generating the work, it’s an open question as to whether those outputs themselves are protected. So, both the input and output questions are unresolved and complicated.

HLT: We saw the song get scrubbed from TikTok and some other places it initially appeared on the web, thanks to attorneys representing Universal Music Group. What are their best arguments for why it should be taken down?

Tompros: To understand what they were doing, you have to understand a little bit about how takedowns work in the copyright context. There is a process under the Digital Millennium Copyright Act which allows a rights-holder to give notice to a third party like YouTube or Apple Music that a work they are distributing is, in the rights-holder’s view, violating their copyright rights. And then, to protect certain rights that those platforms have under the DMCA, the platforms have to immediately take it down. This is what’s traditionally called a “DMCA takedown.”

It’s a little unclear precisely what Drake and The Weeknd’s attorneys did to get this song taken down. There is reporting that says that it was taken down using the DMCA, and that makes sense, because procedurally that’s really the only way that you can get a platform to take down something very fast. But what’s not entirely clear is what argument they actually made in their DMCA takedown requests. There is some reporting that says that it actually wasn’t taken down on the on the basis of it being a copy of Drake and The Weeknd’s style, but in fact, was taken down because of the express copying of a “producer tag” in the song by a producer called Metro Boomin. That tag apparently appeared in the AI-generated work, which is not a huge surprise, because if you are trying to generate something in the style of Drake, you would probably include some kind of a producer tag in it. If that were the source of the DMCA takedown notice, that would make sense, because that’s a direct copy of somebody’s audio, even if it’s something short like a producer tag. But again, it’s not clear what exactly they asserted in their DMCA request, because these filings are not made publicly in front of a court.

I think in terms of the broader copyright arguments Drake and The Weeknd’s counsel could potentially make, there could be arguments based on both the input and output. They might argue that this AI-generated song was the result of training the AI on Drake’s works, and to do that, someone had to copy Drake’s works into this system, and that copying was an act of copyright infringement. They may also try to make the argument that the output itself is some form of copyright infringement, because it is derivative of those artists’ works.

In my view, their best argument is not a copyright argument at all, but a right of publicity argument. There is clear precedent in California and other states under state law that says essentially that a musical impersonation of a famous musician violates that musician’s right of publicity. The most famous case is one Bette Midler brought against Ford in 1988, which went all the way up to the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals. Essentially, Ford produced a commercial for the Mercury Sable, and they wanted to use the Bette Midler song “Do You Want to Dance.” She did not want to give permission for that, so they hired a Bette Midler impersonator and had her do the song. The Ninth Circuit held that when you have a distinctive voice of a professional singer that is intentionally imitated to sell something, that’s a violation of the right of publicity under state law.

That seems pretty straightforward here, where there’s an intentional imitation of Drake and The Weeknd, for the purpose of some kind of a commercial use. The problem with a right of publicity claim is there’s no DMCA takedown remedy. Drake and The Weeknd wouldn’t have been able to get the song taken down immediately; they’d have to file a state claim and go through a typically slower process.

HLT: Based on the Copyright Office’s current guidance, the person who fed Drake and The Weeknd’s music into AI and asked it to create a new song from that material probably can’t be considered the song’s author. But are there arguments for why the song also didn’t violate those artists’ copyright rights?

Tompros: I think there are some good arguments that the creator of the song would have for why it’s not copyright infringement. The first is on the input side. There’s no question that someone put those artists’ songs into the AI, and that is a copy for sure. But the creator of the AI song could say that that is protected fair use, and therefore not copyright infringement. The First Amendment protects freedom of speech, and it’s a check on the scope of the copyright laws. There is a section of the copyright statute addressing fair use, which outlines factors that weigh against copyright infringement. The argument might be that AI training is not something that’s being done to make a copy for commercial purposes; it is instead deliberately transformative and trying to create something new, and there is no direct impact on the market for the original by allowing an AI to hear or see a copy of the original to be able to create to train its algorithm.

The second argument the creator might have is on the output side. If what Drake and The Weeknd are claiming is that this is a copy of one of their songs, or is a derivative of one of their songs, the really simple argument that the AI creator has is ‘No it’s not. The lyrics are different, the music is different. It’s a different song, and you don’t have rights to this.’ If I, as a person, listen to a whole bunch of Drake music and write my own song, having been inspired by him, but I don’t use the same lyrics or the same music, everybody would agree that’s not a copy. Why wouldn’t the same standard apply to an AI?

HLT: In your view, how does AI-generated music compare to other industry-disrupting technologies like music sampling?

Tompros: When sampling really took off, there was a huge set of copyright questions about it, but they were a bit more straightforward than the ones in the context of AI. With sampling, there’s no question that it’s a copy. If I literally take someone else’s riff and put it into my song as a sample, I’ve copied, end of sentence. The question just becomes whether it is fair use or not, and in sampling, that turns on how much of the thing you sampled and how necessary it was, and how transformative what you did with it was as compared to the original.

In the classic Supreme Court case about sampling, 2 Live Crew took part of Roy Orbison’s “Pretty Woman,” in fact, a pretty iconic part of it, and that was ultimately found to be fair use, because it was transformative in nature and took only the amount that was necessary to reference back to and change it.

With AI, unlike sampling, you’re not just taking a piece, you’re taking the whole thing. The AI got a copy of the whole Drake oeuvre, the entire collection of Drake songs. But on the flip side, the output doesn’t include anything at all copied from the originals. This makes it a more complicated calculus from a fair use perspective. But in terms of industry disruption, there’s no question that AI is materially affecting the music industry, like it’s affecting so many industries, and it’s going to be up to the legal system to sort it out.

“The balance between artists’ rights in protecting what they have done and artists’ rights in creating something new is exactly the balance that has underlaid copyright law since it was embedded in the Constitution.”

HLT: How do we go about balancing the protection of artists’ rights to their own materials with promoting innovation in music?

Tompros: I think the balance between artists’ rights in protecting what they have done and artists’ rights in creating something new is exactly the balance that has underlaid copyright law since it was embedded in the Constitution.

First, there’s the pure market perspective. We want to encourage people to make new music, and we need to consider what most effectively encourages new music, and where we draw the line in protecting old music to encourage people to create new music. Thinking about it from this purely economic perspective, would Drake have made those songs and sold those albums if he knew that somebody else could come along later and do this with AI? Maybe, but that’s a tough question. Then there’s the purely creative perspective. When authors and musicians make something, they think of it as theirs and they want to be able to control it. At the same time, we can’t shut down other people’s free speech rights; it can’t be that just because I made something, that means that you can never talk about the thing that I made or improve on it.

At the end of the day, both of those things need to be held in balance. For the last 100 years, there has been a constant effort in copyright law to keep up with new technologies in a way that continues to create incentives and protect artists.

HLT: What, if any, legal changes do you think are needed to address AI-generated art?

Tompros: I would love it if there could be a thoughtful and robust statutory amendment to the Copyright Act to try to address these changing technologies. I think that is probably unrealistic, in part because doing any kind of federal legal change is hard, and we add on to that the fact that the Copyright Act has to synchronize with a variety of international treaties. So, I think the odds of there being AI-focused Copyright Act statutory changes are quite low, though not impossible.

More likely, what we’re going to see is evolution from the courts on how they deal with these issues as they come to grapple with AI. I think we are also going to see some continued regulatory action from the Copyright Office, but there are three areas where I hope and expect the courts to give us some greater clarity in the coming months and years. One is, we need to see case law that either agrees with or disagrees with the Copyright Office on whether AI can be an author or not. The second thing that would be valuable is consensus among the courts as to whether copying for the purpose of training AI is, or is not, fair use. Third, I’m hopeful we’ll get a better degree of clarity on whether an AI work that is in the style of someone else is or isn’t a derivative work.