The October 2023 Supreme Court term contained no shortage of consequential cases touching on everything from social media disinformation to the administrative state, to gun and water rights, and much more.

Over the last nine months, Harvard Law faculty members previewed for Harvard Law Today the key arguments in these and other prominent cases and offered ideas on how the Court might weigh the legal questions they were asked to decide. Here, they share their thoughts on where the justices ultimately landed — and on the longer-term implications of the Court’s decisions.

This post will be updated.

Texas v. New Mexico and Colorado: Water rights along the Rio Grande

This spring, Andrew Mergen, faculty director of the Emmett Environmental Law and Policy Clinic and a visiting assistant clinical professor of law, told Harvard Law Today that the Supreme Court’s ruling in Texas v. New Mexico and Colorado — a complicated and long-running case involving apportionment rights to the waters of the Rio Grande — could have wider implications for millions of Americans. In a narrow 5-4 decision authored by Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson ’96 and released on June 21, the Court rejected a proposed consent decree by the states that the federal government had not approved. Below, Mergen explains why he believes the case — although “not considered particularly exciting” — was rightly decided, and how it could impact water rights in the West.

“This case arises under the Supreme Court’s original jurisdiction over cases between states. In 2013, Texas sued New Mexico and Colorado alleging violation of the 1938 Rio Grande Compact which “effect[ed] an equitable apportionment of the Rio Grande’s waters between the three states.” Texas alleged that excessive groundwater pumping in New Mexico was diminishing supplies of Rio Grande water bound for Texas. As is the practice in such cases, a special master was assigned to gather facts and preside over the dispute. The United States moved to intervene in the litigation.

The United States’ decision to intervene was hardly surprising. On the Rio Grande, as on many arid western rivers, the United States had, beginning in 1906, invested in massive infrastructure to, among other things, store and deliver water. The Bureau of Reclamation, which administers this infrastructure, is obligated to deliver water from the Elephant Butte Reservoir. Although the United States is not a party to the compact, it makes deliveries from the Elephant Butte reservoir which effectuate compact obligations. In 2018, the Supreme Court allowed the United States to intervene in light of its compact duties and also because the United States has a responsibility under a 1906 treaty with Mexico to deliver water to that nation. The United States’s claims in the litigation were essentially the same as those advanced by Texas.

After several years of litigation, Texas compromised its claims against New Mexico and a settlement between these states was reached. (Colorado’s distribution of water was never really in dispute). The United States objected to the entrance of a consent decree settling the matter. The United States argued that as a party, its claims could not be settled over its objection.

In a 5-4 decision, Justice Jackson agreed with the United States. Justice Jackson explained that where, as here, the United States is a party to a case, the claims of the United States cannot be settled over its objection. Further, Justice Jackson found that the United States, even though not a party to the underlying compact, had valid claims against New Mexico.

Interstate river disputes like this one are not considered particularly exciting and, as here, are often assigned to the most junior justice. But these cases are important because river systems are, as a result of climate change, increasingly under stress. The water of the Rio Grande serves both agricultural and municipal purposes in an extremely arid region.

Hence, it is not surprising that Justice Gorsuch [’91] wrote a vigorous dissent complaining that the majority opinion violates 100 years of the Court’s water law jurisprudence. The crux of Justice Gorsuch’s argument is that the states and the states alone govern the water rights of the users in their jurisdictions. In light of this state authority, Justice Gorsuch contends that the United States cannot spoil the settlement the states have obtained.

My view is that the majority has the better of the argument. The United States has an important role to play on the Rio Grande. It administers the works that deliver the water to users downstream of the reservoir and it alone has a responsibility to Mexico. To be sure, Justice Gorsuch is correct that it has long been understood that the states are primarily responsible for water allocation. But on river systems throughout the arid west and elsewhere the United States has distinct responsibilities related to water quality, to Indian Tribes and to, among other things, endangered species. And it is often federal infrastructure that stores and delivers water. Better settlements will be obtained with the Unted States in the mix. Nowhere is this truer than in the case of the Colorado River, a source of water for over 40 million people, where stakeholders are desperately seeking equitable allocation of this oversubscribed river.

NetChoice v. Paxton: Social media regulation

In February, free speech expert Rebecca Tushnet spoke with Harvard Law Today about several then-pending Supreme Court cases, including NetChoice v. Paxton, testing whether states like Florida or Texas can impose content moderation regulations on global social media platforms in an effort to curb what some, including Texas Governor Gregg Abbott, have called viewpoint discrimination. At the time, Tushnet, Harvard’s Frank Stanton Professor of the First Amendment, said that, “[i]f the states can impose this kind of regulation on platforms, we will know that the past 70 years or so of First Amendment jurisprudence can no longer be relied on in any real way.” On July 1, all nine justices agreed to remand the cases back to lower appeals courts for further examination of the First Amendment issues at stake. Asked for her take on the decision, Tushnet wrote:

“It’s excellent that the majority recognized that Texas’ and Florida’s desire to rejigger public debate to favor conservatives was an impermissible reason to regulate platforms. Much remains to be seen on remand, and, more broadly, we are starting to see a forking of conservative positions on free speech and corporate power, which will take years to settle out.”

Ohio v. EPA: Cross-state air pollution

In February, Richard Lazarus ’79, Charles Stebbins Fairchild Professor of Law, told Harvard Law Today that the outcome of Ohio v. EPA — in which Ohio, an upwind state with air polluting power plants, challenged an Environmental Protection Agency rule, the Good Neighbor Plan, designed to limit the flow of air pollution into downwind states — could say a lot about future federal efforts to regulate air pollution. On June 27, the Court by a vote of five-to-four vote temporarily halted the plan’s implementation. Here is what Lazurus, an environmental law expert and keen Court observer, had to say about the decision:

“In February 2016, the Supreme Court sent seismic waves over the field of environmental law when it peremptorily stayed the implementation of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s Clean Power Plan, which was the Obama administration’s signature program for combatting climate change and was based on a massive, yearslong, highly technical administrative record. The plan restricted for the first time greenhouse gas emissions from the nation’s existing fossil fueled power plans. What made the Court’s ruling so extraordinary was that the case was still pending and undecided before the D.C. Circuit, which had denied a request for a stay on the ground that no irreparable injury would occur from the rule while that court considered the merits of a legal challenge to it. Yet, by a five-to-four vote, the justices shut the rule down only a few days after being asked to do so, based on only a cursory briefing and no apparent serious deliberation.

“Yesterday, the Court’s decision to stay EPA’s Good Neighbor Rule limiting interstate air pollution that interfered with downwind state’s ability to protect public health, made clear that staying of important EPA rules is now the norm rather than the extraordinary exception. The majority reasoned that EPA’s rule should be stayed because the rule was likely arbitrary and capricious and therefore legally invalid. Once again, the vote was five-to-four. Justice Barrett wrote the dissenting opinion, joined by Justices Sotomayor, Kagan, and Jackson, in the first four female-only justice opinion in the Court’s history. To be sure, the Court this time did not take only a few days to rule to rule that EPA’s rule should be stayed because it was likely to be determined invalid as arbitrary and capricious by the lower court. The justices heard oral argument and deliberated for many months. But the portent for EPA rules, and likely other significant federal agency regulations of business activities, is the same: The longstanding presumption of the validity of agency regulations no longer holds.”

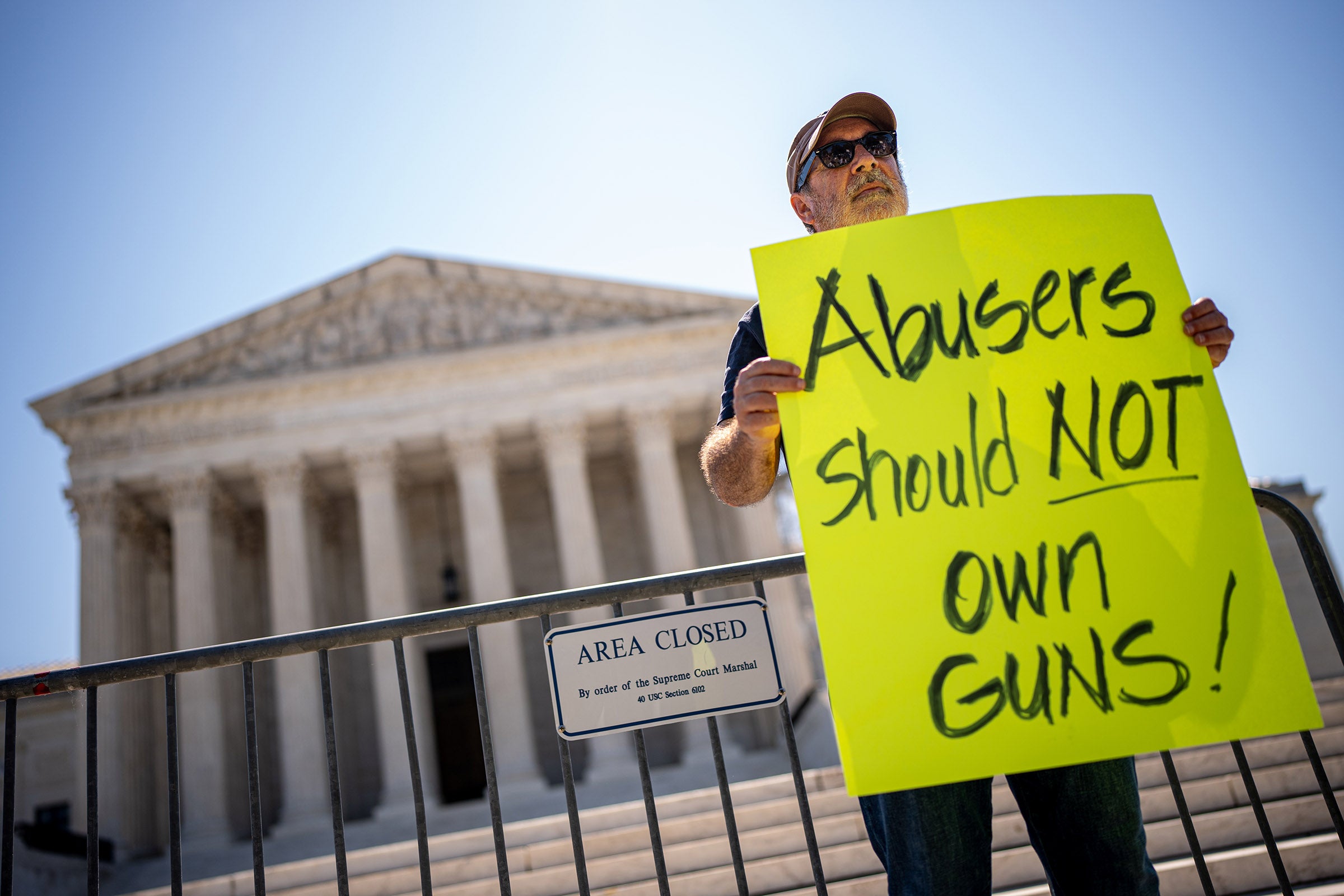

United States v. Rahimi: Gun rights

In October, Harvard Law Today spoke to Mark Tushnet, the William Nelson Cromwell Professor of Law, Emeritus, about United States v. Rahimi, a case that tested the constitutionality of a federal law that prohibits someone convicted of violating a domestic violence restraining order from possessing a gun. Tushnet explained that Rahimi followed a 2022 decision striking down New York’s restrictions on carrying a gun in public on originalist grounds, setting up a new framework for interpreting the Second Amendment. But on June 21, in an 8-1 decision — with only Justice Clarence Thomas in dissent — the Supreme Court upheld the law prohibiting Rahimi from owning a gun, and sought to clarify its originalist approach, as Tushnet details below.

“The result in Rahimi was foreordained. The defendant was such an unattractive person — an obviously violent domestic abuser — that there was no way that five justices were going to let him off the hook. Several justices took the case as an opportunity to write little essays — something like 2L essays in a constitutional theory seminar — about where originalism is likely to go. I think that the Court’s more recent conservative appointees, Justices Kavanaugh and Barrett, realize that their more senior colleagues, Justices Thomas and Alito, have painted originalists into a corner and are trying to figure out where to go once the paint dries.”

Acheson Hotels LLC v. Laufer: Standing in disability cases

Last fall, Michael Ashley Stein, the co-founder and executive director of the Harvard Law School Project on Disability, told Harvard Law Today that much like other civil rights laws, so-called “testers” play an important role in enforcing the requirements of the Americans with Disabilities Act. In Acheson Hotels v. Laufer, the plaintiff sued a hotel group for lacking details about accessibility on its website, arguing that the missing information prevented her from fully participating in society, which was a stigmatic and dignitary harm. The defendants countered that Laufer did not have standing to sue, since she had not intended to stay at the hotel and therefore suffered no actionable harm. On December 25, a unanimous Supreme Court declared Laufer’s case moot, as Stein explains below.

“L aufer was decided procedurally, with the Court vacating the case as moot following on Ms. Laufer’s voluntary dismissal of pending cases under the Americans with Disabilities Act and representation that she would not file further suits. In so holding, the Court punted on deciding the permissibility of standing as it relates to plaintiffs with disabilities acting as testers in cases in which places of public accommodation did not post accessibility information on their websites as required by the Reservation Rule promulgated by the Department of Justice.

“Writing for the majority, Justice Barrett noted that the Court might “exercise our discretion differently in a future case.” Concurring in the judgment, Justice Thomas concluded that Laufer — whom he characterized retrogressively as “wheelchair bound” — lacked standing in that she was not personally discriminated against in her role as tester. Justice Thomas’ opinion opens the door to lower federal courts restricting the ability of disability rights attorneys acting as case testers of places of public accommodation in the future that violate the Reservation Rule, whether as in this case a hotel, or conceivably for other more essential services such as medical care providers, private schools or colleges, or day care centers.”

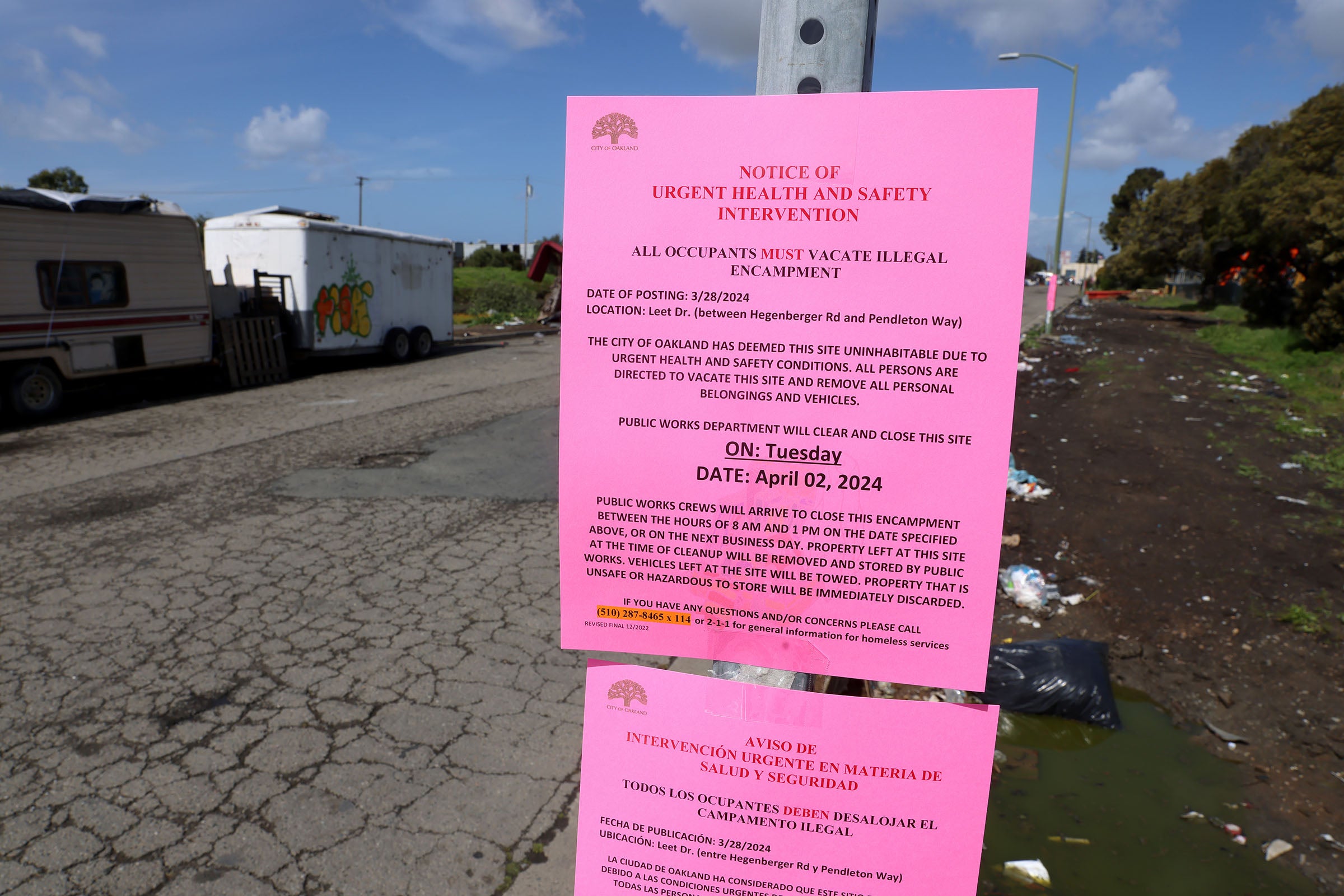

City of Grants Pass v. Johnson: Homelessness and cruel and unusual punishment

This past spring, Carol S. Steiker ’86, the Henry J. Friendly Professor of Law, told Harvard Law Today that the Supreme Court’s decision in City of Grants Pass v. Johnson, which involved a ban on camping on public property, could impact more than just homelessness — it could upend the very meaning of “cruel and unusual punishment” as prohibited by the 8th Amendment. Steiker, a leading expert on capital punishment, worried that the Court could abandon its previous “evolving standards of decency” approach in favor of an interpretation fixed in time. In a 6-3 opinion authored by Justice Neil Gorsuch ’91, the Court upheld enforcement of the law, reasoning that it was “generally applicable” and did not constitute cruel and unusual punishment.

In a follow up conversation, Steiker identified a few major takeaways from Gorsuch’s opinion. First, on a practical level, she says, “It seems clear to me that the Court was motivated by the number of cities and states that filed amicus curiae briefs, including San Francisco, detailing what they call the homelessness crisis in their cities.”

Steiker notes that it is rare for the Court to cite extensively from amici briefs, as Gorsuch does in explaining the “need” for cities to have tools at their disposal to deal with homelessness.

For advocates who want to continue to fight anti-homelessness laws, Steiker says that it is clear that the answer will not be found under the 8th Amendment. But she adds the decision does not preclude constitutional challenges under the 4th Amendment’s bar on unreasonable search and seizure or under the due process clause of the 5th and 14th Amendments.

Further, on a jurisprudential level, “The decision signals a continuing shift in the way the Court has interpreted the cruel and unusual punishments clause for well over half a century,” Steiker says.

As she detailed previously in Harvard Law Today, the 1958 Supreme Court case Trop v. Dulles first established the “evolving standards of decency” test. But instead of following that, Gorsuch quotes from a previous opinion he wrote, 2019’s Bucklew v. Precythe, “where he says that the right way to think about the meaning of cruel and unusual punishment is to look at what that meant at the time of the founding, which is an originalist/textualist approach,” says Steiker.

Steiker adds that Gorsuch’s opinion calls into question the future of the “evolving standards of decency” test. “He doesn’t say anything about the long list of decisions the Court has rendered under the test, and it’s not clear if any of those would survive under Justice Gorsuch’s methodology.”

Although the majority does not outright reject the 66-year-old standard, “the mode of Gorsuch’s analysis is markedly different from what the Court has generally accepted as 8th Amendment analysis,” Steiker says.

Steiker points out that the Court has not been shy about overruling other longstanding precedents in recent years. “Is this a signal that the 8th Amendment in its sights?”

Want to stay up to date with Harvard Law Today? Sign up for our weekly newsletter.