Mitt Romney ’75, CEO and president of the Salt Lake Organizing Committee, plans for a safe and sound Winter Olympics

Mitt Romney ’75 doesn’t exactly fit the image of a hard hat kind of guy. But the graduate of Harvard’s law and business schools grabs his hard hat–stamped with the Olympic symbol–in the same way other people who wear business suits grab their briefcases, as if he wouldn’t go anywhere without it. He’s leaving his downtown Salt Lake City office, striding to one of the many Olympic sites in the final stages of construction about 100 days before the biggest event that has ever hit this city. And he’s in the middle of it all, an omnipresent force in a community that for years and years has been girding, with an equal mixture of excitement and trepidation, for a fortnight in February. The Winter Olympics will go on here, he is almost sure of it, and he has spent most of the past three years preparing for the best and the worst that the Games has to offer. It’s not the kind of job where your hands get dirty and your muscles ache at the end of the day. But, considering what he faced when he arrived on the job and what he has faced since then, he has earned the right to call the hard hat his own.

In February 1999 Romney became CEO and president of the Salt Lake Organizing Committee (SLOC), a white knight called in to save an organization in disarray and a city in distress. At the time, the Justice Department and the FBI had just launched investigations into a bribery scandal, in which members of the Salt Lake Bid Committee had offered International Olympic Committee officials money and gifts, reportedly in excess of $1 million, in exchange for hosting the Games. (In November, a federal judge dismissed fraud charges in the case against two committee officials; the Justice Department is considering an appeal.) The scandal, said Romney, “dispirited and devastated the psyche of this community and probably the entire Olympic world.” There was another problem too. The original budget for the Olympics, about $800 million, had proven to be low–more than $1 billion low, in fact. And the SLOC, responsible for 70 percent of the cost, had secured only a pittance of the $500 million needed in sponsorships to balance the budget. “We were in a severe financial crisis,” said Romney.

No one’s talking much about those issues anymore. That, of course, is primarily because of the security concerns that have surrounded the Olympics since September 11. But it’s also because–long before September 11–Romney worked to solve the problems, something he had grown accustomed to doing in a business career that was a springboard to one political campaign, and perhaps more to come. He made turnarounds his specialty as the founder and CEO of Bain Capital, which acquired or started more than 100 companies, including Staples, Domino’s Pizza, and FTD Florists.

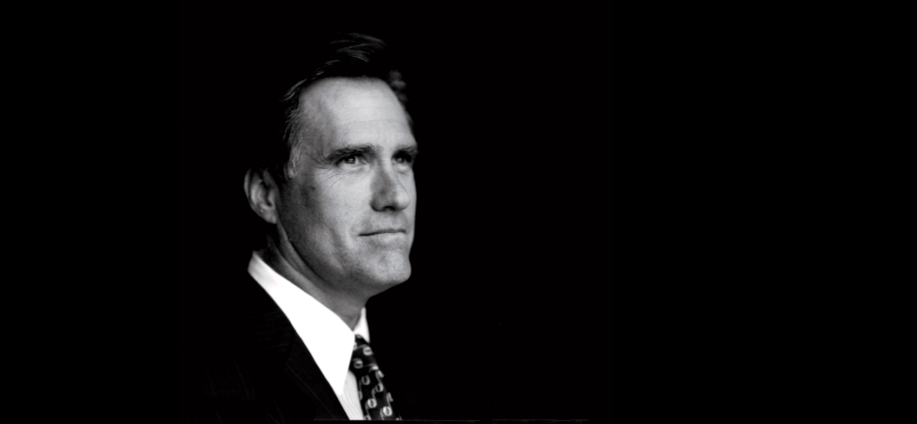

Credit: Louisa Gouliamaki AFP/Corbis Mitt Romeny 75, CEO and President of the Salt Lake Organizing Committe, plans for a safe and sound Winter Olympics

“The experience that I’d had before was very much akin to what I faced here, although the complexity and the scale of the challenges here were beyond what I’d experienced before,” said Romney.

When he began, he followed the principles he’s always followed. He told people the truth, he said, about how bad things were and how he was going to make things better. He brought in people he knew and trusted, including Fraser Bullock, a colleague from Bain Capital who serves as chief operating officer of the SLOC. He implemented stringent ethical standards, opening meetings and making documents available to the public, and requiring employees and board members to report potential conflicts of interest and complete an annual survey of ethical conduct. He evaluated the finances and cut the budget by $200 million. He hired a sales staff and courted potential sponsors, touting the Olympic brand and “the great qualities of the human character that tend to be displayed in these moments on the world stage.”

He did all this not only to regain trust and achieve fiscal stability but to place the emphasis back on the athletes. It is perhaps the only goal he couldn’t accomplish.

Playing It Safe

Interviewed in his office in late October, Romney had spent the previous day responding to inquiries about an International Olympic Committee official who was quoted as saying that a country at war should not host the Olympics. The official said he was misquoted, spoke to Romney, offered unqualified support for the Salt Lake City Games. But the questions still lingered, as they had since September 11: Would the Games go on? Should the Games go on?

Credit: AP Photo/Douglas C. Pizac Mitt Romney displays a poster of an Olympic pin shortly after the terrorist attacks.

“I think it’s going to be clear that some people will not want to proceed with the Games,” said Romney. “There will be some people who consider the financial considerations and are concerned financially. There will be others who think about political implications and may want to withdraw for some reason. But I think when you consider the sacrifices made by the athletes who get ready for an Olympic Games and the years of training and coaching and the expense they take on, as well as the personal sacrifice they make, you have to proceed with the Olympic Games if it’s at all possible.”

Every athlete he spoke with urged him to do whatever was necessary to hold the Games, Romney said. Jacques Rogge, International Olympic Committee president, predicted in November that not a single athlete would opt out of competition. “Mitt Romney and the Salt Lake City organizers . . . have done a superb job to ensure the athletes will be well served and provided with the optimum chances to perform at their best,” Rogge said during a National Press Club speech.

Romney and Rogge sent letters to every national Olympic committee to reassure athletes that their safety will be a priority. They have pledged the same vigilance for spectators. The security plan, coordinated by the Secret Service, calls for 7,000 law enforcement personnel to monitor threats from the ground and from the air.

They will search everyone who enters an Olympic venue and everyone who enters a six-block area of downtown Salt Lake City, which will be fenced in for the Games.

There is no evidence that terrorists will target the Olympics, an event that encompasses the world and not just its host country, Romney said. And while no one claims that handling an influx of more than 200,000 people will be easy, it is more straightforward–particularly if enough money is devoted to public safety–than protecting an entire country at war and at risk. Shortly after the terrorist attacks, Romney traveled to Washington to meet with lawmakers and Bush administration officials, who promised an additional $40 million for security. The total bill for security now stands at more than $300 million, an extraordinary sum, he said, for 17 days of events in one relatively small community.

“I don’t think there will be another event in the world that will be as thoroughly protected as this one,” said Romney. “This will break all records, in terms of funding for security and the provision of personnel and equipment to assure the public. So I feel as good as you can feel in America these days.”

Romney personally thanked President Bush (who is scheduled to attend opening ceremonies on February 8) for his support of the Salt Lake City Olympics during a meeting in late November. The two were classmates at Harvard Business School. But in graduate school Romney seemed the more likely candidate to someday occupy the White House.

Born to Run

The son of the late George Romney, former governor of Michigan and a onetime presidential candidate, Romney avers that he held no political aspirations when he was a student or early in his career. He was more focused on not flunking out of law school (he said hornbooks saved him), juggling the workload with his business studies, and finding a good first job. Yet, Romney said, “My dad is someone who I’ve subconsciously patterned my life after. He was someone who had a very strong sense of public service, which is something that, as I’ve gotten a little older, seems to have sprung up in me as well.”

Credit: Chris Stanford/Getty Images Muhammad Ali clowns around with Mitt Romney during the Olympic torch relay at Atlantas Centennial Park in December.

His subsequent success in the business world gave him the freedom to follow his father’s example. He claims little credit for his financial gains; if you didn’t make money as an investment manager in the ’80s and early ’90s, he says, you were in the wrong profession. It was like winning the lottery, and just as some lottery winners grasp the opportunity to change their lives, so did he. Except instead of retiring to an island somewhere, he decided to run for the U.S. Senate against Ted Kennedy in 1994. It was not unlike the U.S. men’s hockey team going up against the Soviets in the 1980 Olympics. But at least in that competition, the U.S. team had the home advantage.

“If I were aiming towards politics, it would have been Michigan, where I could have built on personal relationships and an extraordinary reputation for my father and my mother,” said Romney. “Massachusetts was not the place for a white, male, Mormon millionaire Republican to consider a political life.”

He learned a lot from that race, in which he garnered 41 percent of the vote. One lesson, Romney often jokes, was never to run against a Kennedy in Massachusetts. The Kennedy campaign was widely credited for cementing a victory by questioning the business practices of a man who prizes ethics in personal and civic life. Even with the bruises of the campaign, however, Romney also learned that he would like to run for office again.

He just doesn’t know when or where that race will be. In August he announced that he would not return to Bain Capital in order to “look for opportunities to make further contributions in the public service arena.” He has a home in Belmont, Mass., but said he will not run for governor against Jane Swift, a fellow Republican and acting governor of the state. Utah, where he has a second home in Park City, is a possibility too. Before starting at the SLOC, he lived in the state full-time only when he was a college student at Brigham Young University, but his roots there run deep. His parents were raised in Utah. His great-grandparents walked across the plains to get there, part of a migration of people seeking religious freedom who established the headquarters of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

That heritage motivated him to leave a comfortable life in Massachusetts. So did his wife, Ann, who was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis shortly before he was offered the SLOC job. Ann, an equestrian and skier whose health has improved in the great outdoors of Utah, convinced him that he was ideally suited to help a city that was being defined by scandal, Romney said. And there was another reason.

“The Olympics has a very noble purpose, and I’ve become sort of philosophical in this regard, but it has a very important purpose on the world stage, and it was in trouble,” he said. “That was an overwhelmingly powerful draw for me.”

Peak Experience

Local planners are encouraging Salt Lake City residents to work the 6 a.m. to 2 p.m. shift during the Olympics. Or better yet, they say, people should try telecommuting. “Sleep in, arrive early, eat late,” said John Sittner, director of Olympic planning, at a Winter Olympics open house in October that was part pep rally, part warning cry. Planners have mapped out how every moment of the Olympics will affect every street and highway in the area. The mantra is: Know before you go–to the office, to the store, to walk your dog.

It will be a disruption alien to people accustomed to wide-open spaces and a state capital with a placid downtown. For a long time, Utahns debated whether the Games would benefit the region. If it’s like past Olympics, it may not add much to the local economy. In fact, Romney doesn’t blame residents who never wanted any part of the event at all. “I’m not sure if I lived in Salt Lake City at that time, whether I would have wanted the world to come to my city, and fill up my canyons with homes and vacation places and pollution,” he said. “But once you bid for the Games and you’re selected, in my view and in the view of the great majority of people in Utah, you now have a commitment to follow through and to host the world and to prepare for the athletes.” And, he added, when the 2002 Olympic Games are a memory, “What I hope will be said is that Salt Lake City endured remarkable challenges to hosting the Games, but they carried them out in a way that did the world and America proud.”

Credit: Doug Pensinger/Getty Images

As the final preparations proceed, he believes most residents are asking not what the Olympics can do for them, but what they can do for the Olympics. Hoping for 22,000 volunteers, the SLOC had 67,000 applicants. Hoping local businesses and donors would contribute $50 million, the SLOC received $150 million. The community, Romney said, has shown its character, the character of the American West, independent but united if called upon to serve a greater purpose.

Some people may not see nobility in, say, someone riding a sled around a track of sheer ice. In truth, most people don’t watch these sporting events except at the Olympics. Even the Olympic qualifiers, such as a short-track speed skating event at the Delta Center in the fall, attracted only a few hundred people. But the Games transcend sports, Romney said. He has met many of the greatest Olympic athletes, and what distinguishes them is not their physical ability, he said, but their human spirit. He thinks of Kerri Strug, the gymnast who told him that she felt pain a hundred times worse than she’d ever felt in her life when she tore ligaments in her ankle during the vault competition at the 1996 Olympics. Her team needed her to do the vault one more time to have a chance at a gold medal. So she did. And if a hero is someone who takes risks for the benefit of someone besides herself, then Strug is a hero, he said. Romney isn’t afraid to say that he still believes in heroes.