For Spencer Churchill ’15, one of the most enduring lessons of law school so far has come not from a reading assignment or a research project.

He learned it from a child.

On the outside, the 12-year-old girl, who went to an urban school near Boston, seemed well behaved and in control, but she was failing her classes. When Churchill started representing her to try to secure her special services as part of his work at the Education Law Clinic at Harvard Law School, he gradually discovered she was dealing on the inside with so many problems in her life, it was “almost more than you would believe could happen to one kid that age.”

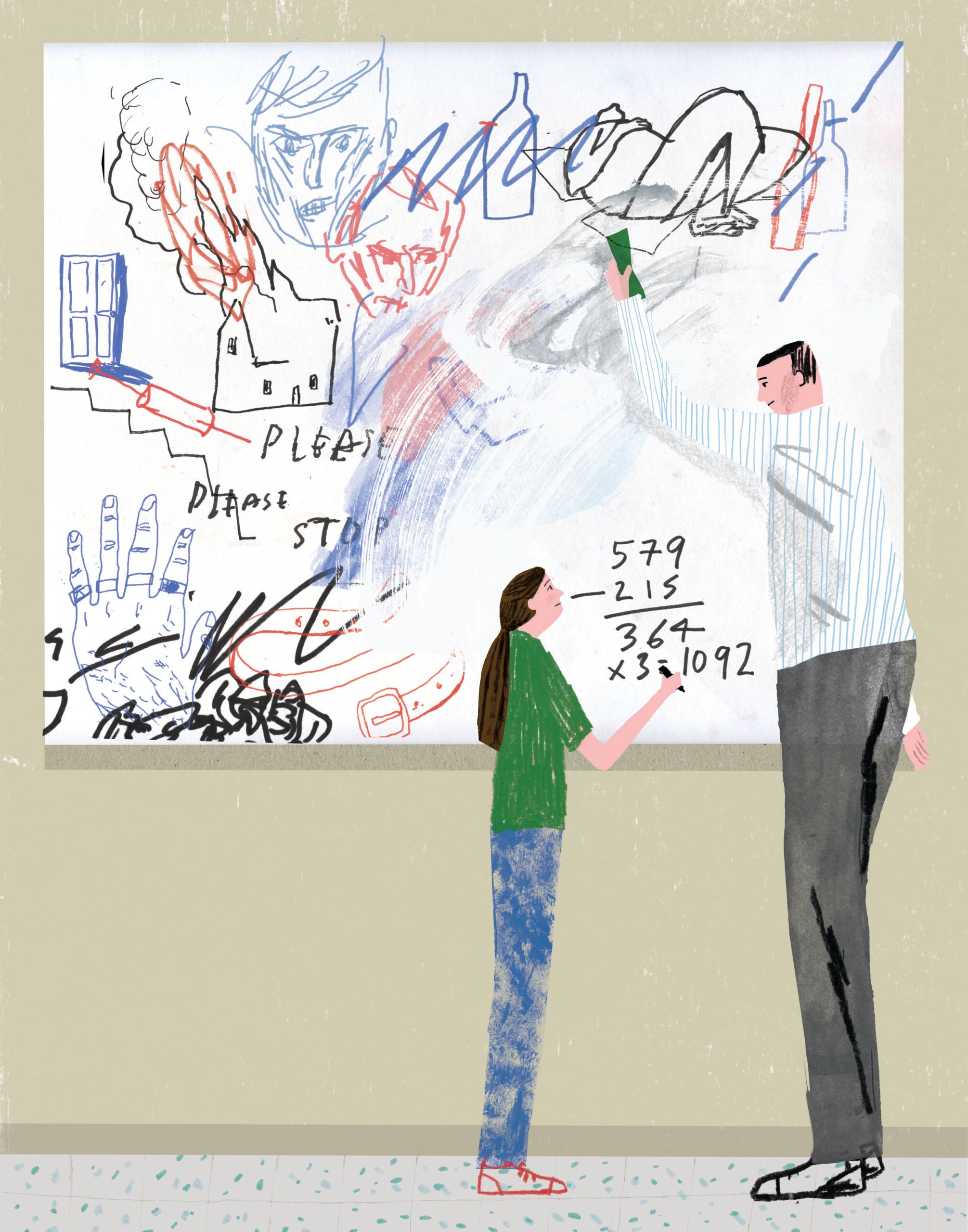

Taken from her single parent because of neglect, intermittently homeless and severely bullied at school, the girl put so much energy into trying to hide what was happening to her that “she had little bandwidth left to focus on her work,” says Churchill. “And she fell through the cracks. Everybody felt she must not be smart because she wasn’t doing well. She wasn’t acting up, so she wasn’t getting help.”

While the behavior of some students who have experienced traumatic events gets them suspended or expelled, other students, like the girl who Churchill represented, fly under the radar.

For the past 10 years, students and faculty of the HLS clinic have been successfully advocating to get such students back on the education track. And in July, after a yearlong effort, they helped to pass—against great odds—a pioneering Massachusetts law to provide much broader protection for students at risk by supporting schools to do such things as aligning existing anti-bullying and dropout prevention programs, recognizing warning signs of stress, and providing positive reinforcement rather than knee-jerk discipline.

Many people may not know that this effort is connected to HLS, says Sara Burd, districtwide behavioral health coordinator for the public schools in the Massachusetts town of Reading, who is involved in the movement to create trauma-sensitive schools.

“I think that speaks to the humility of the people involved,” Burd says. “But they were essential.”

Churchill says legislators also seemed surprised to find Harvard Law students advocating for the law. Representatives or aides would often ask him why he cared.

“Getting to know this child, who had been through so much and who was so misunderstood,” says Churchill, “and having seen how the system really does miss people who need help—that created a sense for me that there was an injustice.”

For Susan Cole, understanding the link between trauma and behavior also started with a child.

A lawyer and former special-education teacher, Cole began to work as an attorney for Massachusetts Advocates for Children in 1988. By the early ’90s, the nonprofit found itself coping with a wave of student expulsions from schools that resulted from a zero-tolerance provision of a Massachusetts education reform law.

The law empowered principals to throw students out of school for misconduct that purportedly threatened the safety of classmates or teachers. But it made no provisions to educate them unless it could be proved they had disabilities that qualified them for special education.

In just two years, the number of expulsions shot up by more than 50 percent. Cole began representing many of these students, trying to get them back in school.

That’s when she met a 15-year-old in foster care, removed from his mother’s custody because of neglect and then from his father’s because of abuse. He had been expelled from school for two full years, and during that time, he went in and out of the juvenile justice system.

The boy had been kicked out of school after fighting with another child and touching the teacher who tried to separate them, a basis for expulsion under the education reform law, Cole says. In the course of trying to have him certified as eligible for special education, Cole took the boy to a psychologist who was a trauma expert.

What the expert told her left her speechless.

“She said, ‘Drop all of those other diagnoses. This child has post-traumatic stress disorder.’”

When Cole took those findings to a hearing to return the boy to school—that this 15-year-old had the kind of PTSD that is suffered by combat soldiers—“You could have heard a pin drop,” she says. “People at that time didn’t understand the underlying reasons why a student might be acting this way.”

The boy was admitted to a school that could address his emotional needs, and Cole “got to see the transformation of a really bright young man,” she says.

But it also had a much broader impact. Cole began thinking back to other children she had taught and represented who didn’t fit neatly into the special-education category, wondering whether they were victims of traumatic experiences.

To widen families’ access to legal help, in 2004, Cole helped create the Trauma and Learning Policy Initiative, a collaboration between Massachusetts Advocates for Children and HLS, of which she is now the director. That same year, she also founded the school’s Education Law Clinic, where children and their families can get legal help securing education services.

And she and her colleagues started asking parents if their children who had been expelled from school had previously been exposed to violence.

“We were shocked at how many parents were saying, ‘Yes,’” Cole says.

The prevalence of trauma in American society was not well documented until as recently as the late 1990s. The first revelation of its impact on children in particular came in a 1997 study by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which found that two-thirds of 17,000 people surveyed had suffered at least one adverse childhood experience of some kind, including witnessing domestic violence, being sexually or physically abused, or having a parent who used illegal drugs or was in prison.

“The frequency of traumatic experience among children was far higher than anyone had ever imagined,” says Joel Ristuccia, a veteran school psychologist who is the initiative’s training director and also the lead professor in a graduate trauma certificate program at Lesley University. “It was a real wake-up call.”

Work by neuroscientists including Jack Shonkoff, professor at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, and Martin Teicher, director of the Developmental Biopsychiatry Research Program at McLean Hospital, has linked childhood trauma to developmental problems. Its victims, they have found, are often unable to focus on learning or to trust adults. They often suffer from hopelessness, lack of control and diminished self-worth. Remembering traumatic experiences triggers anxiety that suppresses the area of the brain associated with language, making it difficult for them to communicate effectively.

“It’s only in the last 10 years that we’ve gotten a complete picture of how significantly trauma can affect kids’ learning,” Ristuccia says.

A study of elementary school students in Spokane, Washington, found that children who experienced trauma were two to four times more likely to skip school, act out or bring other problems to the classroom. U.S. schools suspend more than 3.3 million students annually, according to the National Education Policy Center, 95 percent for reasons other than using drugs or carrying weapons. In Massachusetts, many students who were expelled from school in one district just dropped out of the educational system, since no other district had to take them.

But recently, in part because of the research that underlies the movement for trauma-sensitive schools, says Jerry Mogul, executive director of Massachusetts Advocates for Children, “you’ve started to see the pendulum swing back and people start to think about, ‘OK, what happened to these kids?’”

Michael Gregory ’04, too, was inspired by a child.

When Gregory was student-teaching in Providence as part of his work toward a master’s degree in teaching at Brown, he was frustrated by a pupil in his 10th-grade English class who had already failed the course twice. The young man’s father was in prison, his mother was nowhere to be found, and he was living with a sister barely older than he was.

“He was really bright, but he wasn’t able to focus,” says Gregory, “and I couldn’t reach him.”

Gregory says he came to HLS because he “wanted to address these issues as a lawyer, as an advocate.” He began working with Cole in the Education Law Clinic after graduation, and this fall was promoted to clinical professor (effective Jan. 1, 2015). He also teaches the elective he took as a first-year student, Education Law and Policy.

He and Cole began to realize that helping individual families was making only incremental inroads into the broader educational problems faced by many traumatized children. It was clear to them, especially once researchers began to document the breadth of the problem, that what was needed was to change the culture of schools.

“There are way more traumatized students than lawyers to represent them,” Gregory says. “What we need to do is create whole-school environments that help all students learn, that are calming, that feel safe.”

As part of that effort, Cole and Gregory, in partnership with Massachusetts Advocates for Children, co-wrote the landmark publication “Helping Traumatized Children Learn,” which came out in 2005. Colloquially known as the Purple Book, it has become a go-to resource for educators, advocates, and parents, and has been bought or downloaded more than 100,000 times, with requests for translated editions coming from as far afield as Brazil and the Netherlands.

The goal of the Purple Book was to raise awareness among educators about trauma, the effects it can have on learning, and the need for a schoolwide approach to helping students. Recently, the team published a second volume, “Creating and Advocating for Trauma-Sensitive Schools,” based on five years of work in Massachusetts schools, led by Ristuccia and Deputy Director Anne Eisner. By both working in schools and representing families, the initiative “uses a unique model of social change that brings the voices of educators, parents and children together,” says Gregory. These perspectives led to the second volume’s expanded policy agenda, which calls for change at the district and state levels to support educators in this work.

To help bring about that change, the clinic began to focus more on legislative advocacy. In 2008, it helped to push through the Massachusetts Legislature a bill that addressed the need for schools to promote the social and emotional well-being of all students. That law established a task force to consider ways that students with mental health challenges, including those affected by trauma, could be served in schools—not just suspended, expelled or overlooked. The idea was to transform the whole learning environment.

The commissioner of education appointed Cole and the other initiative members to serve on the task force, which issued its final report in 2011, making recommendations to the Legislature. The HLS team then went to work to put the task force’s recommendations into law.

Some schools in Massachusetts and in other states had already begun experimenting with creating trauma-sensitive learning environments, many in collaboration with the Trauma and Learning Policy Initiative.

In an elementary school in Brockton, south of Boston, educators got a graphic representation of the issues many of their students were facing when a social worker from the district attorney’s office superimposed the coordinates of gun and drug offenses over a map of the school district. Gasps were heard in the room, the principal, Ryan Powers, later recounted for a New York Times blog. But then the teachers went to work. For students who had trouble grappling with their emotions, they set up beanbag chairs in quiet corners, gave them headphones to listen to classical music or excused them from class to go for walks. Police began letting schools know when they visited an address where children live so counselors could look out for problems. Eisner and Ristuccia worked closely with the school, and after two years of integrating this new approach, the number of students sent to the principal’s office with discipline problems plummeted by 75 percent.

In Lynn, on Boston’s North Shore, an elementary school set up a committee to look after students whose behavior might be a sign of trauma. After they identified one struggling boy, they learned that several of his mother’s boyfriends had physically abused him. Few activities seemed to engage the boy, but when members of the committee learned he loved to play baseball, they arranged for him to join a team. The activity and the attention helped stabilize him. In the past, his behavior would have simply led to expulsion.

After a string of drug overdoses among students, public schools in Reading, also north of Boston, bulked up their mental health staff, added more breaks in preschool and kindergarten classes to keep students focused, put dozens of teachers through Ristuccia’s program at Lesley on the impacts of trauma, and assigned them to read the Purple Book.

“We started to notice a huge trend where kids were really struggling with a lot of social and emotional needs,” says Burd, the behavioral health coordinator. Now, she says, “to have the grounding and the science and the research makes [the Reading teachers] such confident professionals when it comes to dealing with the emotional needs of students.”

“Traditionally, schools are not structured to offer that kind of thing,” Burd says. “You not only need to know what the kids are dealing with; you have to have all these supports” on top of teachers’ and administrators’ other obligations.

Creating trauma-sensitive environments “means you have to completely change your work, the way you see the field, your day-to-day job—and change is terrifying,” she says. “Especially when you don’t have the confidence that everyone is going to change with you.”

As the recommendations of the statewide task force were being fashioned into legislation early this year, the Education Law Clinic was temporarily transformed into a legislative clinic.

Over the course of the 2013-2014 academic year, its five students—alongside Cole, Gregory and Eisner, a clinical social worker with 30 years of experience who works with clinic students—set out to lobby for the bill. Known as An Act Relative to Safe and Supportive Schools, it calls for a statewide framework to help all schools create trauma-sensitive environments. It provided a comparatively small $200,000 for a grant program to fund early adopter schools to serve as models of this new approach. Advocates say they foresee little additional cost, since most of what the law requires is better coordination of existing programs or reallocation of resources.

The odds were long. “We talked with representatives who had a good deal of experience, who pretty much seemed to take it for granted that the bill wouldn’t be passed this year,” remembers Churchill, “but by raising its profile [we thought] it would have a pretty good chance of being passed next year.”

Gregory and Cole convened a lobbying boot camp for their students, gave them transit passes to go back and forth to Beacon Hill, and sent them on a scavenger hunt around the Statehouse so they could familiarize themselves with its geography. The students wrote scripts and practiced them together, and then set out to gather the support they needed.

From an original 36 backers, the team and its allies among other advocacy organizations managed to cultivate 55 legislators by the end of the semester. In the end, 97 voiced support for the law. “Every day the students were coming in here and saying, ‘I got another one,’” Gregory says. And by convincing legislators to include the Safe and Supportive Schools provisions in legislation tightening gun regulations—a hot topic strongly backed by the Massachusetts speaker of the House—they helped to get the measure voted in, just one day before the end of the legislative session.

“It passed!!!” Gregory wrote in an ecstatic email to the clinic students, who had by then dispersed for the summer.

Two weeks after that, Gov. Deval Patrick ’82 signed the provisions into law.

“We were elated,” says David Li ’15, another student in the clinic, who also worked as a teacher before he came to HLS. “I honestly had to reread the email to make sure that it was right.”

The Education Law Clinic, which has resumed representing clients, will have to lobby again next spring to renew the funding for the law it helped get passed. Cole and other members of the HLS initiative have been appointed to serve on the Safe and Supportive Schools Commission, which must submit an annual report on what schools need to implement the law, along with recommendations for future legislation to address these needs.

But in the meantime, the experience proved that advocacy works, Cole says.

“Five students,” she says, “can change the world.”