Eliot Spitzer’s zeal for justice has made him enemies and friends. It may also make him governor.

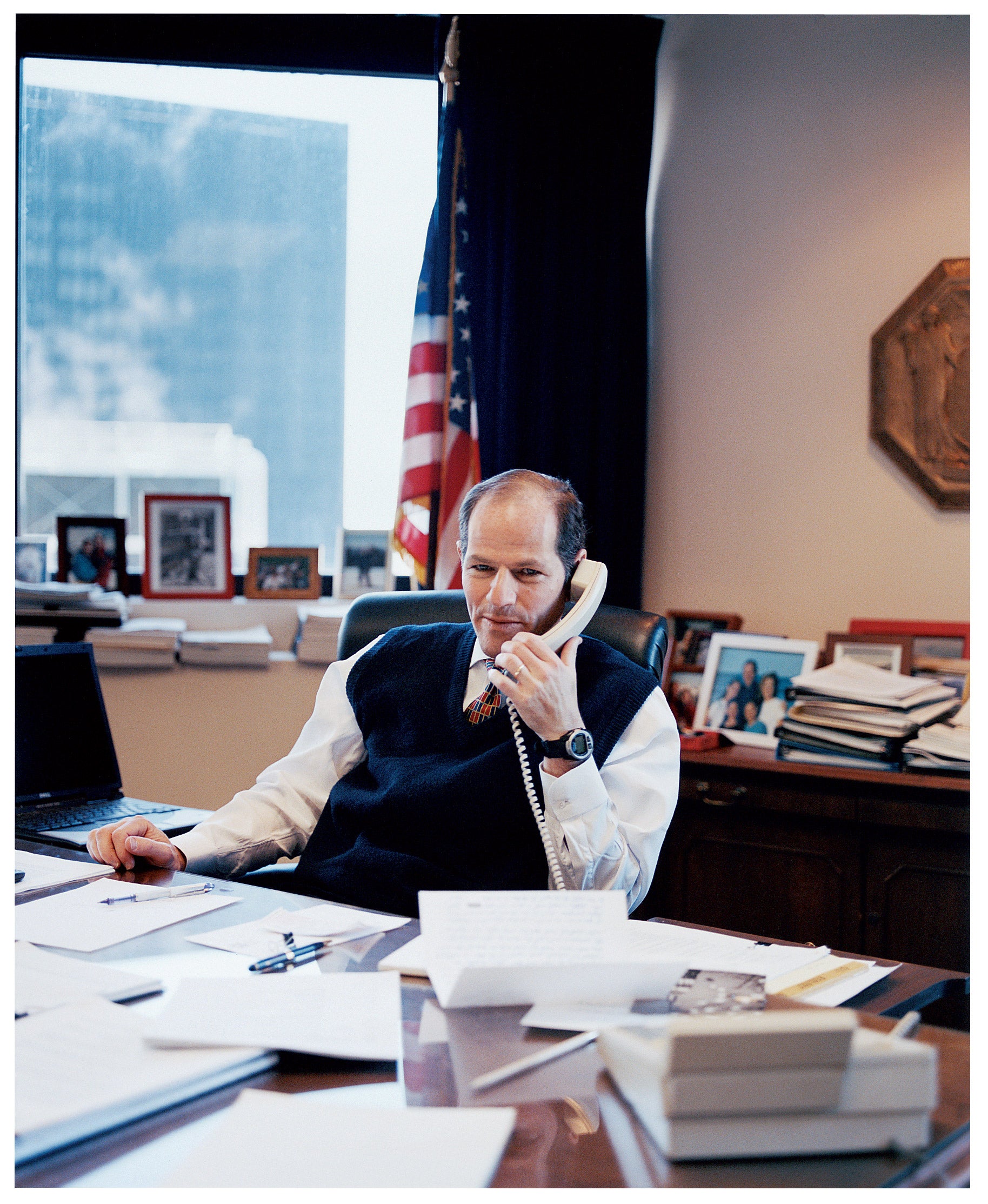

Eliot Spitzer ’84 has no time to waste. Instead of hello and a handshake, the New York state attorney general greets a visitor with “OK, let’s get to work.”

On a stormy day, from the 25th floor of his Lower Manhattan office building, Spitzer is preparing for a press conference to announce a $600,000 settlement with Macy’s department stores–a result of his investigation into complaints that African-Americans and Latinos were unfairly targeted for shoplifting arrests. He has also just brokered an $850 million settlement with Marsh & McLennan over insurance bid-rigging allegations. And, of course, he is in the early stages of his campaign to be elected governor of New York in 2006.

It’s all in a day’s work for Spitzer, New York’s attorney general since 1999, who is hoping that his high-profile investigations into conflicts of interest in the financial services industry, polluting power plants and low-wage labor violations by grocery stores will catapult him into the Empire State’s highest office. “The problem-solving nature of this job has prepared me for the governor’s office,” says Spitzer, 45, noting that he is excited by the prospect of moving into the policy-making position once held by his political role model, Theodore Roosevelt, whose sepia portrait hangs on his office wall.

Even outside New York, Spitzer’s image is becoming familiar. His trim face, protruding jaw and intense gaze have accompanied recent articles in magazines ranging from The Economist and The Atlantic Monthly to Vanity Fair and People. While Spitzer is celebrated as a populist, a reformer and a champion of civil rights, he has also become a familiar target for critics who say that many of the issues he takes on are better left to the federal system. Last June, National Review described him as “the most destructive politician in America.” And U.S. Chamber of Commerce President Tom Donohue has blasted his corporate prosecutions, calling him “the investigator, the prosecutor, the judge, the jury and the executioner. It is the most egregious and unacceptable form of intimidation that we have seen in this country in modern times.”

Spitzer does his best to ignore the comments, which–positive or negative–tend to be extreme. “Our job is just to enforce the law,” he says. “I reject the notion that the cases we are making are out of a political agenda.” Early in his tenure as attorney general, Spitzer says, he was told that taking on powerful targets would end his political career. But he has maintained that he is not so concerned about his political career that he won’t pursue transgressions at the highest levels.

He also shrugs off concerns that he is spread too thin–that his rapid-fire probes are not carefully prepared. “We are always cognizant of the allocation of resources,” says Brad Maione, a spokesman for Spitzer’s office, which includes more than 600 lawyers, 1,800 employees and an annual budget of $191 million. Although some investigations result in settlements, the office is not afraid to go to court, says Maione, pointing to the high-profile, ongoing litigation involving former New York Stock Exchange Chairman Dick Grasso’s controversial $187.5 million compensation package.

This was not the career Spitzer imagined for himself as a student at Harvard Law School. “I thought I’d clerk, spend a few years at a firm, a few years at a prosecutor’s office, and then go into business with my dad,” he says, referring to his father, Bernard Spitzer, a self-made multimillionaire real estate developer. Instead, he followed a path into public service. He did clerk, for U.S. District Court Judge Robert W. Sweet. And he was an associate at Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison. He also worked at the New York law firm of Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom and was a partner at Constantine & Partners. In between his stints in the private sector, he served as an assistant district attorney in Manhattan from 1986 to 1992, rising to become chief of the Labor Racketeering Unit, where he successfully prosecuted organized crime and political corruption cases.

In a strange coincidence, the prosecutor who promoted Spitzer to chief of that unit, Michael G. Cherkasky, now heads Marsh & McLennan, which the New York attorney general’s office has charged with rigging bids for property and casualty insurance contracts and favoring insurers that paid higher incentive commissions. It is another turn in his career that Spitzer says he never would have predicted. “He’s a friend,” Spitzer says of Cherkasky. “He was brought in to restore integrity to the company.” Skeptics have wondered whether Marsh & McLennan chose Cherkasky to lead the company this past fall because of his ties to Spitzer. Cherkasky could not be reached for comment for this article, but in November he told Forbes, “We’re not going to pay one dollar less in restitution than if I wasn’t here. It’s just not going to happen.”

Spitzer looks back fondly at his HLS days. He forged lasting friendships and political alliances there, and it is where he met his wife. Among his favorite classes were a seminar on international treaties and arms control with Abram Chayes ’49 and a corporate tax class with Alvin Warren. He also admired Alan Dershowitz, for whom he worked as a research assistant when Dershowitz was defending Claus von Bulow. “He was one of my favorite students,” recalls Dershowitz, who remembers Spitzer as “the library guy” and says, “He was such a shy young man, the only student who always called me ‘sir.'” But, Dershowitz continues, “He is an absolutely first-rate, brilliant lawyer. If I ever started a law firm and Eliot were out there, he’d be the first guy I’d want to hire, based on legal skills.”

Spitzer’s wife and ’84 classmate, Silda Wall, is president of Children for Children, a New York not-for-profit that fosters community involvement and social responsibility in young people through youth service and philanthropy programs. They have three daughters, Elyssa (15), Sarabeth (12) and Jenna (10), and two homes, one in Manhattan and one in Columbia County, N.Y. Spitzer admits that finding a work-family balance is a struggle. He travels at least two days a week as attorney general, and now he is adding campaign activities on top of that. He makes a point of being home by 9 p.m. on weekdays, and he sets aside every other weekend to spend with family.

“He’s a great dad and a great husband, as well as being right on every issue,” says Jim Cramer ’84, Spitzer’s longtime friend. Cramer, a former Goldman Sachs trader who once ran his own hedge fund, is the markets commentator on both CNBC and TheStreet.com. With his ear constantly to Wall Street, Cramer has heard many criticisms of Spitzer’s investigations of the financial services industry. “So many people on Wall Street think he has overstepped,” he says. “I find that somewhat funny. I think the bad guys have overstepped. Eliot has a sense of outrage about what other people see as business as usual. He has a finely calibrated sense of fairness and honesty, and he understands what corruption means.”

In addition to the Wall Street critics, there are those who accuse Spitzer of inspiring other state attorneys general to bring suits that previously would have been the province of the Securities and Exchange Commission, the Environmental Protection Agency or U.S. Attorney’s Offices. Spitzer is fueling a federalism debate over the regulatory and enforcement roles of states’ attorneys general–even though the issue predates his tenure, beginning in earnest with the state tobacco litigation of the late 1990s. But even Spitzer has some concerns over 50 different attorneys general pursuing the same industries in different ways. “I am not thrilled at the notion of a Balkanized regulatory world,” he says. “I am sympathetic to the view that it leads to inconsistency.”

At the same time, however, Spitzer says that a little healthy competition among prosecutors and regulators is beneficial. “Competition works–even in law enforcement and in regulatory agencies,” he says. “Monopolies don’t work in the private sector or in government.” The competition from Spitzer has spurred federal prosecutors and regulators, as well as other states’ attorneys general, to keep pace.

“Balkanization is not a bad thing,” says Dershowitz. “It’s not bad to have different offices with different results. Everyone wants to be Eliot Spitzer now, and that’s a very good message.”

As Spitzer’s reputation as a righter of corporate wrongs has grown, his office has been regularly besieged with phone calls and tips on conflicts of interest and fraud. It has also become routine for people–“serious people,” Spitzer says–to approach him on the campaign trail with new reports of fraud in financial services. “People care about their money, and if they know you will act on tips, they will come to you,” he says. “Success breeds success.”

Even Dershowitz is getting inquiries from people seeking Spitzer’s help. “I get calls from people saying, ‘We got screwed in California. Is there anything Spitzer can do?’ He’s become a symbol of rectitude,” says Dershowitz. “He’d be a phenomenal governor, senator, president–or anything else he wants to be.”