According to HLS Professor Hal Scott, nearly eight years after the 2008 crisis, the U.S. financial system is inadequately protected and more at risk than ever. He sounds the alarm in a new book, “Connectedness and Contagion: Protecting the Financial System from Panics,” forthcoming early this summer from MIT Press.

Scott sets out to debunk the prevailing belief that the 2008 crisis was caused by “connectedness,” the overexposure of giant financial institutions to one another’s insolvency. He recalls the tangible fear after Lehman Brothers filed for bankruptcy in September 2008. Toxic credit default swaps had brought AIG to the brink, he says, “and the idea was if AIG failed, too, it would default on contracts, then Goldman Sachs would collapse in turn, leading to a chain of failures. But the data doesn’t pan out that analysis.”

In fact, connectedness was not the issue at all, he says. “The real problem was contagion,” which exploded after Lehman collapsed and the run on money market funds began. Scott defines contagion as “the indiscriminate run by short-term creditors of financial institutions that can ruin otherwise solvent institutions” due to the fire sale of assets to fund the flood of withdrawals.

Contagion remains a serious threat, according to Scott, because our financial system depends on what he estimates to be $7.4 trillion to $8.2 trillion of “runnable” and uninsured short-term liabilities, 60 percent of which are held by nonbanks—hedge funds, insurance companies, broker dealers, and money market funds.

In September 2008, presidential candidates Barack Obama ’91 and John McCain met with President George Bush and congressional leaders about the Federal Reserve and Treasury’s proposed $700 billion intervention known as TARP (Troubled Asset Relief Program). Enacted on Oct. 3, TARP was immediately dubbed the “Wall Street bailout.” Democrats paid heavily in the November 2010 elections for having passed it.

With the 2016 election approaching, almost every presidential candidate still talks about the bailout “as a bad thing,” Scott says. “But when crisis hits, people want to get their money out, so there is a run on banks and other financial firms, contagion erupts, and unless those firms get immediate help, they will go bankrupt and ultimately the entire economy will collapse.”

Contagion is the reason the Federal Reserve was created in the first place, in 1913, Scott says. “We had a series of panics in the 19th century that caused recessions, and then the Panic of 1907, when J.P. Morgan saved the day” by making massive personal investments and urging his counterparts to do the same, to fend off runs. Following that, “the general feeling was, ‘We can’t put the financial system’s fate in the hands of one person,’ so the Federal Reserve was formed.”

In the 2008 crisis, the Fed lent massively to banks and nonbanks alike to slow the run on assets. The Treasury used the Exchange Stabilization Fund, originally created in the 1980s to address exchange rate problems for emerging countries, to guarantee the money market funds in crisis. To further calm the waters, the FDIC raised deposit insurance from $100,000 to $250,000, and to an unlimited amount on transaction accounts.

The Dodd-Frank Act was a major response to the bailout, Scott says, but it was based on the incorrect connectedness diagnosis. “The general sentiment was, ‘What the Fed did was bad; we need to strip powers.’” He describes the act as “two wings and a prayer—the wings are capital and liquidity, and the prayer is resolution [measures].” He continues: “There are good reasons to require [banks to have] more capital, but it’s all gone in a heartbeat if there is a panic. And if you claim ‘we can resolve troubled institutions effectively,’ many people will still pull out funds. None of this solves contagion.”

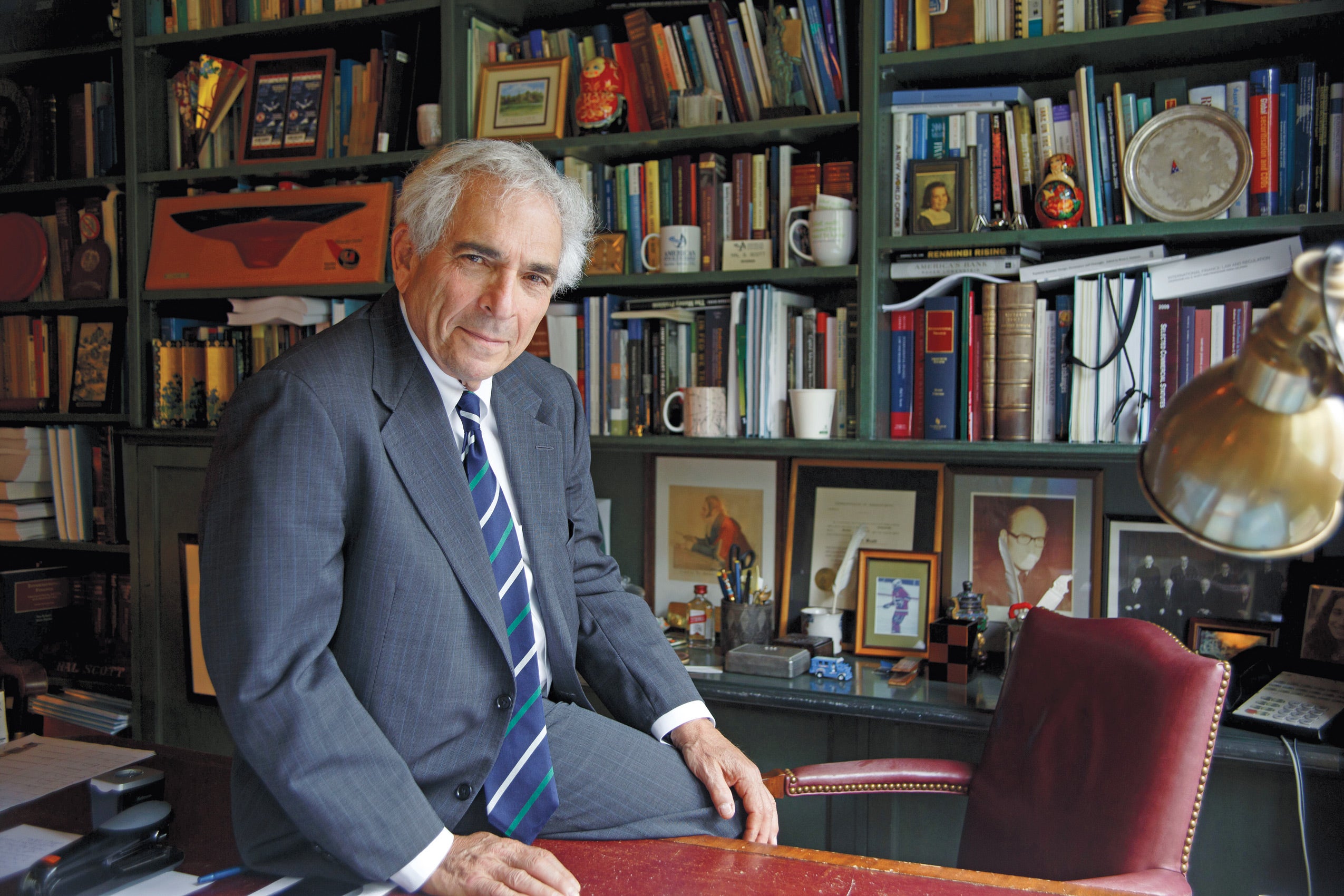

Since 2006, Scott has been the director of the Committee on Capital Markets Regulation. The group’s members represent all elements of U.S. financial institutions, from big banks and leading hedge funds to accountants, lawyers, and academics. “We’re not just a think tank: We formulate policy positions and try to get Congress and regulators to consider our positions,” Scott says. In 2008, CCMR members recognized contagion was the real danger, he adds. Today they observe the waning of the Fed’s powers with alarm.

“The political environment [in Washington] remains intensely hostile to the Fed’s role as lender of last resort. If we have another financial crisis, we are toast,” Scott says. “Very few people, especially elected officials, will speak to this.”

And so he is doing exactly that. Forensic in approach, “Connectedness and Contagion” lays the groundwork for what Scott hopes will happen when the public and politicians stop fixating on “bailout”: reinstatement of contagion-fighting weapons.

This isn’t about just the U.S., he adds. “This is about the dollar, the world’s reserve currency. We now have the weakest of the five most powerful central banks. The dollar and U.S. are at the pinnacle of the economic system of the world, but could collapse because we don’t have a strong enough lender of last resort. This is a global issue.”