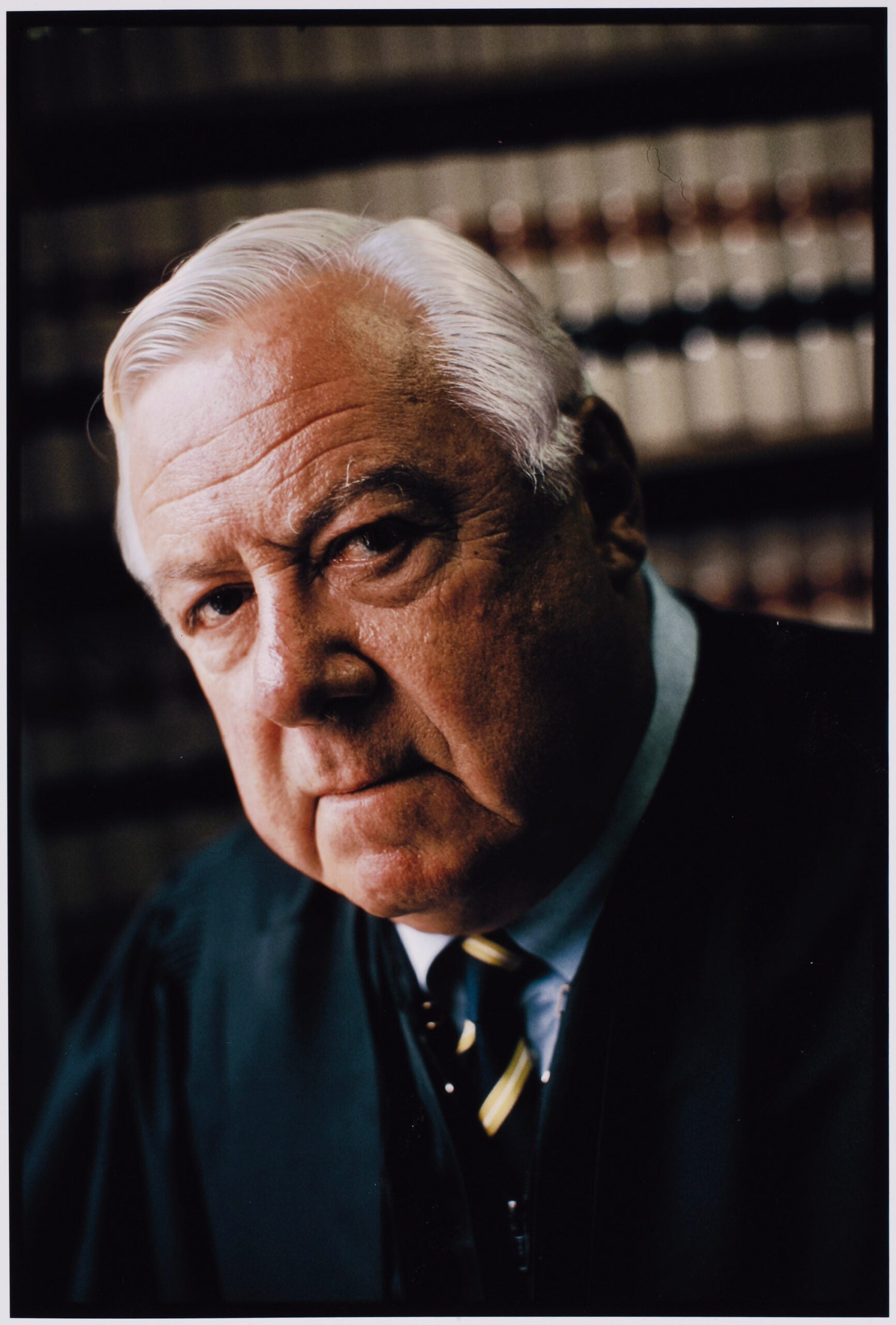

Like Captain Jack Aubrey the larger-than-life hero of his favorite works of fiction, the celebrated seafaring novels by Patrick O’Brian, U.S. district Judge Thomas Penfield Jackson ’64 is a blunt, plain-speaking, and physically imposing man who knows how to run a tight ship. From the moment he drew judging duties for United States v. Microsoft, Jackson was determined to keep one of the 20th century’s largest antitrust cases running swiftly and on course. Whereas the historic IBM and AT&T battles dragged on for 13 and 16 years respectively, the latter consuming the lion’s share of his colleague Judge Harold Greene’s time, Jackson wrapped up the Microsoft case in fewer than 80 trial days by limiting witnesses and making lawyers submit testimony in writing, among other measures. He issued his findings of fact in November 1999 and his conclusions of law in April 2000. In a 43-page ruling Jackson found that Microsoft Corp. had violated antitrust laws by bundling its Internet Explorer software with its dominant Windows operating system in a move to stifle competition in the Web browser market. Microsoft had “placed an oppressive thumb on the scale of competitive fortune, the judge concluded.

Earlier, Jackson had prodded the parties toward a settlement. In November he asked appellate judge and fellow HLS alumnus Richard Posner ’62 to help mediate between Microsoft and the federal government, which was joined by 19 states.

I am not a federal bureaucrat, and I have no aspirations to regulate the software industry.

Settlement talks failed, however, and in June Jackson announced his remedy: to split Microsoft into two competing companies. Microsoft is appealing, and in September, the Supreme Court sent the case to the Court of Appeals: Jackson has stayed his judgment pending that appeal.

Although his final ruling strongly criticized the software giant’s conduct, stating that Microsoft “has proved untrustworthy in the past, the judge would have welcomed a very different utcome. No doubt about it, I have always felt that a negotiated settlement in this case was ultimately preferable to any resolution that I might impose, he said in an interview. “I am not a federal bureaucrat, and I have no aspirations to regulate the software industry. I have no animus against Microsoft Corp. and indeed in many respects find it an admirable company, which has in certain respects been of enormous benefit to the new economy. I am a conservative Republican, and to the extent that market forces operating on their own are sufficient to redress any imbalance in the markets, I would much prefer to rely on them.

As a result of the Microsoft case, “I would hope that there would be a general public understanding of the role that I played. I am a United States federal district court judge. I am a trial judge; my court is the court of first impression. There are at least one or more appellate courts that are going to exercise scrutiny of my work product.

The man who became known worldwide as “the Microsoft judge started out with minimal knowledge of the software industry, but his ability to winnow out the key facts earned him the praise of many observers, including Washington Post op-ed writer David Ignatius. He wrote that Jackson “played the role of judicial Everyman in this case, grappling with the mysteries of the tech wizards.

District judges are generalists, Jackson noted, and are expected “to acquire one way or another the knowledge that we need to decide almost anything. There is virtually no subject, no matter how abstruse, that will not at some time become the subject of litigation. When a concept or term or abbreviation stymied him, he often turned to his more computer-literate law clerks for assistance. He also credits the lawyers on both sides for walking him through vital technical material. “One characteristic of antitrust cases … is that they usually are of sufficient economic significance so that the lawyers are very good, and it is always a lot easier to preside over a case if the quality of advocacy is superior, he said. “Good lawyers will conduct a seminar in whatever the subject is and educate the judge who has approached the case as a neophyte, to begin with, as I was in the case of software and cyberspace.

In fact, Jackson said, the biggest challenge of the case for him was not the intense media scrutiny or high-stakes issues involved or application of old law to a new economic realm. It was maintaining his focus hour after hour, month after month. “Nobody talked down to me. They discoursed as they would in normal conversation with those who were their technological peers, and I was expected to keep up. I had to concentrate intensely so I would not miss something of significance.

That kind of frankness has characterized Judge Jackson’s 19-year career on the bench. It caused a stir when, on a visit to Harvard, after presiding over the 1990 trial of then D.C. Mayor Marion Barry, Jackson criticized the jury for acquitting Barry on felony drug charges and convicting him on one misdemeanor charge only. “I got in trouble at Harvard on that case, he recalled. “I still think that there were four jurors who in effect managed to accomplish jury nullification. This was one of the cases that precipitated the more public discussion of that issue. It was in the form of a mistrial because other jurors were preparing to convict, but I do not believe that these four were willing to convict under any circumstances.

The judge’s candor also attracted notice more recently, when he took the unusual step of recusing himself in March from considering four D.C. gang leaders’ request for a new trial. In 1994, Jackson had presided over the successful prosecution of the Newton Street Crew drug ring, handing multiple life sentences to the defendants. However, a U.S. Justice Department investigation subsequently uncovered evidence of police and prosecutorial misconduct, including financial incentives for key government witnesses.

About his recusal, which took many by surprise, Jackson said, “I reflected on it for a considerable period of time. It was a hard decision for several reasons. I think the defense attorneys’ request for a retrial is a gnawing question and will be difficult to decide because the allegations made are not trivial or frivolous in any respect. They are very serious claims of misconduct. Being as difficult a matter as it is, I’m hesitant to pass this on to a colleague, to say, ‘It’s too tough for me to decide so I’m going to leave you with this can of worms.’ You don’t like it when it is done to you, and I don’t like to do it to anybody else. The second reason I’m reluctant to give up the case is that I am fully knowledgeable about it. I worked on it for five months, I have a very firm conviction of the guilt of these defendants, and I do not want to see them released from confinement. I think they received exactly what they deserve, and I hope society has seen the last of them. And that probably is precisely the reason why I shouldn’t settle the case, because my inclination would be to superimpose my own conviction of their guilt upon any analysis of whether they had received a fair trial. And third, he added, “I got to know the prosecutors who handled the case. They are all very fine young lawyers, and I probably would be inordinately disposed to do anything I could to protect their reputations, if not their careers, rather than do what the evidence would tell me I had to do. In the end, Jackson said, “I was convinced that I could not be open minded, and when a judge feels that way, then it is time to relinquish that case.

A third-generation Washingtonian, Jackson attended Dartmouth College and Harvard Law School. He found adjusting to HLS rather hard because he was coming off a three-year stint in the Navy, where he had risen to a senior level of junior officer on a destroyer. “I felt pretty cocky about myself. His choice of Harvard was not a given because his father felt some antipathy toward the School. “My father was a graduate of George Washington University Law School. When he interviewed around town, they told him, ‘Well, you’re a very promising lawyer, but you are not Harvard Law School.’ While the son did not relish the grueling HLS experience, he said, “I had no misgivings about the quality of my education; it was superb. I was convinced I was ready for any legal experience.

After HLS Jackson joined his father’s firm, Jackson & Campbell, where he specialized in medical malpractice and insurance cases and earned a reputation as a formidable litigator, as well as a commanding courtroom presence. He became increasingly involved in local Republican politics and served as attorney to President Nixon’s reelection campaign in 1972. In 1982 Ronald Reagan appointed him to the federal bench. It was not, said Jackson, “as difficult a transition as you might think, going from lawyer to judge, because you have lived with the system for so long that you know from personal experience what qualities you expect to find in a good trial judge. You try to as great an extent as possible to exhibit those qualities: patience, attentiveness, decisiveness, intelligence, interest, a willingness to be open-minded, courtesy, and respect for counsel and for witnesses and juries.

As judge, Jackson has found that “the hardest test for somebody whose prior professional experience has been a lawyer is to keep his mouth shut and to refrain from interfering with the work of the lawyers. In every trial there are instances in which the judge who has been a trial lawyer thinks, ‘I wouldn’t have asked that question’ or ‘I would have taken a totally different approach to that witness’ or ‘I would never have called this witness.’ The Microsoft case offered many such moments, particularly the defense’s use of Bill Gates’s videotaped deposition, which was widely critiqued for the evasive responses of the company chairman.[pull-quote content=”I have no misgivings at the moment about the result that I reached in any respect.” float=”left”]

While United States v. Microsoft is by far the most-watched legal dispute of his career to date, Jackson has had several other high-profile cases. In 1998, he ordered the government of Iran to pay millions in damages to former U.S. hostage Terry Anderson and others who had been kidnapped in the 1980s. In 1994 he ordered former Oregon Senator Robert Packwood, who was accused of sexual misconduct, to turn over his notorious diaries to the Senate Ethics Committee. And in 1987 he fined former Reagan aide Michael Deaver $100,000 for lying about his lobbying activities.

Jackson has also had cases he found at least as technologically complex as the Microsoft battle. He boned up on automotive engineering and vehicle dynamics to rule on the government’s 1987 complaint that General Motors Corp. knowingly sold more than one million 1980 X-cars with alleged defective brakes. (Jackson rejected the government’s claims.) As for other hard-to-manage cases, he cites the trial of Marion Barry “because the racial overtones were so intense throughout. And indeed I think they ultimately played a significant role in how the case was finally resolved. (Jackson sentenced the mayor to sixth months in prison for cocaine possession.) That case also featured a dramatic incident, “the sudden appearance of Louis Farrakhan and a cadre of escorts who attempted to enter the courtroom en masse, to be visible to the jurors and as, I suspect, a measure of intimidation. I excluded them from the courtroom but was reversed by the Court of Appeals.

A memorable case that came early in Jackson’s years as judge concerned a cancer patient named Martha A. Tune who wanted her life-support equipment removed. He drew upon precedents he knew from his litigation experiences concerning informed consent to medical treatment. He then “simply proceeded from the assumption that if a patient is entitled to be fully informed about the consequences of treatment that she is about to undergo, the converse of that is that once informed, she has the right to demand its cessation. Jackson appointed a former law partner as guardian ad litem for the patient, “who investigated and reported to me as officer of the court that the woman was lucid, competent, and genuinely desirous of ending her forced life support maintenance. His decision to allow this “followed quite naturally.

One of the judge’s favorite cases “got absolutely no publicity here in this country, although I’m told that it was of considerable interest in England. In the 1990 case, War Babes, an organization of children fathered by U.S. servicemen in England during WWII, filed a request under the Freedom of Information Act to obtain the best last-known addresses for the servicemen they believed to be their fathers. “The Department of Defense refused to reveal the information on the grounds that it was an unwarranted invasion of the privacy of these servicemen, explained Jackson. The plaintiffs argued that the DOD had no way of knowing that it was an invasion of privacy, and that in their experience servicemen who were contacted in most instances welcomed the overtures. However, the DOD continued to refuse to release the names. Jackson ordered the department to “affirmatively inquire whether the serviceman would or would not welcome an overture from a child conceived during the war in England. And only in those instances where the serviceman affirmatively declined to be identified would [the DOD] be allowed to withhold the names. That case was never appealed; that’s exactly the way it was resolved. Jackson found the case “very satisfying and “would love to know how it turned out for the war babes and their fathers.

On a late June day the drab federal district courtroom where the Microsoft and government attorneys faced off was quiet and empty. In the decidedly low-tech ambience of his chambers Judge Jackson sat in the midst of prized mementos from his service to Dartmouth, Navy tour of duty, years as lawyer and judge, and family gatherings aboard his 33-foot sloop, Nisi Prius (“Trial Court), which idled throughout the Microsoft trial.

Perhaps he will set sail again soon, for at the moment the judge’s caseload is business as usual, with none of the hoopla that surrounded all matters Microsoft. “That case certainly has received more public attention than anything else I have ever done, he said. His name traveled worldwide via the Internet as well as traditional media. Communications came from as far afield as Australia where a judge in Perth sent Jackson the front page of the daily paper there, “on which I was prominently featured. I figured if I can make the papers in Perth, Australia, then I’ve really become a household name in my 15 minutes of fame.

While he found media coverage of the Microsoft trial generally “pretty good, Jackson thought a “significant shortcoming was the excessive amount of attention that was paid to me—things that I did or facial expressions that I was perceived to have. Very often after an entire day in court in which a lot of significant testimony had gone forward, the only thing that the media paid attention to were the one or two questions that I asked of a witness. And it never occurred, apparently, to the authors of any of these stories that I genuinely wanted answers to these questions. I was trying to learn something. I was not, by any means, sending a signal.

Jackson hasn’t shied away from reading the negative reviews of his decision as well as the laudatory ones. “I can show you some very highly critical comments, not only from Microsoft, he said, but from widely regarded publications such as the Wall Street Journal. “I’ve been shown articles by various columnists whose opinions are certainly worthy of sober consideration. However, a judge’s work requires “a thick skin. Our job is to develop our decision and to justify it with reasons.

Although he has rendered his opinion in United States v. Microsoft, Judge Jackson knows he may well see that case again. Nonetheless, he said, “I am reasonably confident about the outcome. I have no misgivings at the moment about the result that I reached in any respect. I may certainly be instructed to the contrary by the Supreme Court or the Court of Appeals and I will of course do what it is that they tell me to do if they didn’t like the way I did it the first time around.