A first-of-its-kind research center readies lawyers for a changing profession

Thirty-five years ago, most lawyers were white men, few law firms counted more than 100 lawyers, attrition was low and clients were loyal. Attorneys didn’t spend a lot of time thinking about how to market themselves or manage large organizations, let alone how to compete with lawyers abroad.

Today, most lawyers practice in huge institutions—whether in private firms, corporate legal departments or government entities—for clients who demand a full range of sophisticated legal and related services. Technology has spawned the virtual law office, so that lawyers may work for clients they never meet and for whom they face aggressive worldwide competition. And, as women and people of color join the profession in record numbers, white men find themselves a shrinking—though still dominant—percentage.

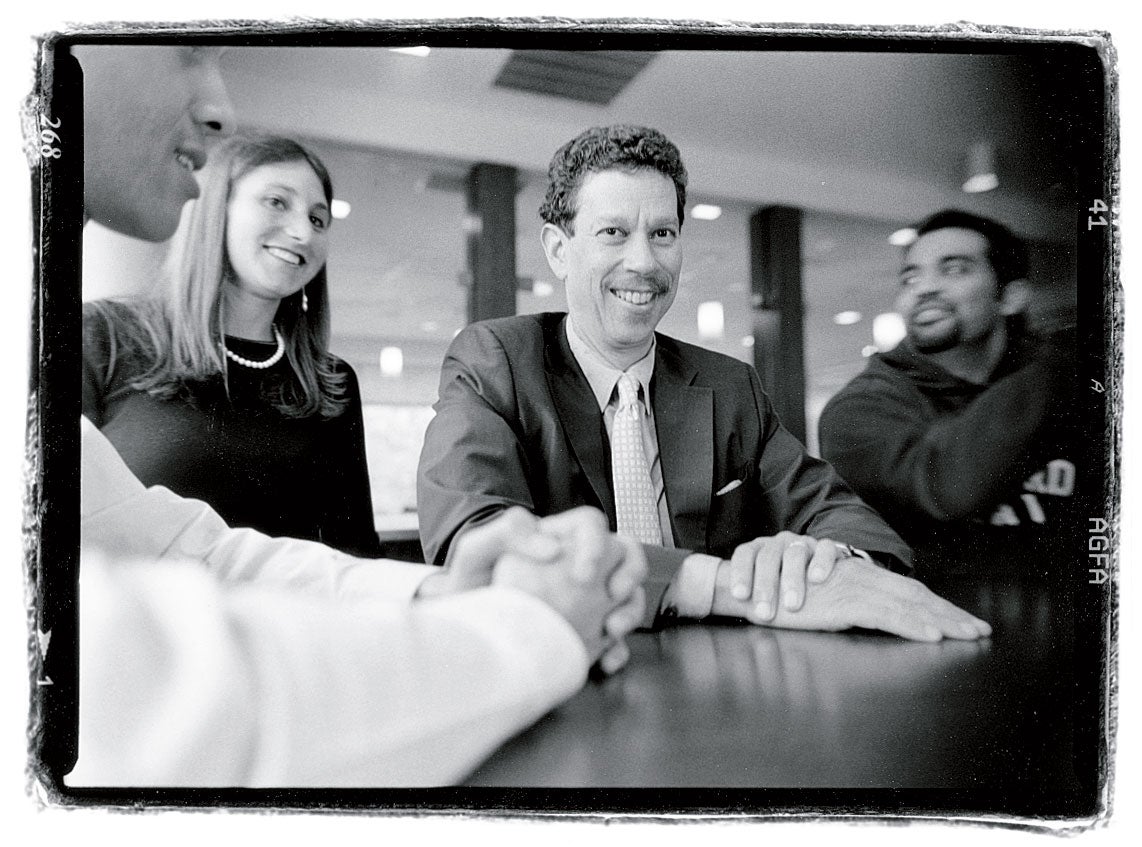

“The legal profession is undergoing a profound transformation—most dramatically in the large-firm setting—and the jury’s still out on where it’s going to settle,” says Kirkland and Ellis Professor of Law David B. Wilkins ’80, director of Harvard Law School’s Program on the Legal Profession.

Survival in this new legal world means adapting fast. Yet there’s been little academic attention paid to these transformations, and a dearth of hard data or reliable guidance on what to do about them.

But that’s about to change. Understanding the new trends and what they mean for practitioners and the wider world is the goal of a new program, the Center on Lawyers and the Professional Services Industry, launched in 2004 as part of the Program on the Legal Profession. The center draws on faculty and practitioners affiliated with HLS, Harvard Business School and the American Bar Foundation, and is the first of its kind to study and provide guidance on the serious challenges facing the profession today.

“No other law school in the world is doing anything like it on this scale and with this commitment,” says Wilkins, director of the new center. “There hasn’t been a major effort by a law school to really examine the transformation of the global market for legal and other professional services.”

The center will focus on three areas: empirical research on what’s happening and why, new approaches to training law students so they can successfully navigate the changing environment, and a vigorous effort to bridge the long-standing divide between the academy and the profession by bringing in top practitioners as advisers and, in return, providing them with training and guidance on the problems they face in the real world.

“There is a crying demand for this,” says Ashish Nanda, a former associate professor at HBS who will be directing research at the center and teaching in a pilot program for executive education of managing partners and leaders of law firms. “Before, law firms were primarily small professional partnerships. They are now large organizations which face the challenge of being a high-quality professional service provider and running a large, complex business effectively.”

Practitioners, especially at large firms and other major professional service providers such as investment banks, confront new and daunting challenges. Many law firms face a breathtaking 25 percent turnover each year as the “old bargain” of the past—in which long-term loyalty to a firm was rewarded by partnership—is no longer the norm. At the same time, global clients demand extremely complex services at competitive prices.

“This is a profession with a lot of nervous breakdowns going on, especially in private practice,” says Ben W. Heineman Jr., General Electric’s former senior vice president for law and public affairs, who, as the program’s first Distinguished Senior Fellow, is writing on topics such as the changing role of corporate general counsel. “Diversity, globalization, how to run a law firm, how to run corporate legal departments, how to integrate foreign-based attorneys with domestic attorneys—there are innumerable issues the profession faces today. The purpose of the center is to study these because that has not been done well enough.”

Law schools have been remiss in providing much-needed resources to students and practitioners during this period of transformation, Wilkins believes. “These changes in the legal profession have a wide-sweeping effect on not just law students and practitioners but also the public, and we have an obligation to contribute to knowledge about the issues in a way we uniquely can do—through unbiased, systematic data—so we can give society the best-trained professionals we can,” he says. “There’s a real hunger on the part of practitioners for some disinterested, detached examination of the issues they face, which is something that only people in an academic setting, away from the day-to-day pressures of practice, can do.”

A multidisciplinary and multi-institutional effort, the center is part of a network of “industry centers” supported by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation. In addition to Nanda, Heineman and Professor Guhan Subramanian ’98—all of whom have close ties to HBS—core faculty include Wilkins; Robert Nelson, director of the American Bar Foundation; and HLS Professor John C. Coates.

New research

How do major corporations purchase legal services today? That’s the focus of a major research project under way at the center, led by Nanda, an international expert on professional service firms, and Coates, who, in addition to being a leading scholar in corporate law, was a partner at the New York firm of Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen, Katz before joining the HLS faculty.

“There used to be long-term, enduring relationships between law firms and companies,” says Wilkins. Many firms were housed in the same building as their primary corporate client. “Over the past 30 years, we know those long-term relationships have broken down in many ways.”

Today, companies purchase services in a wide variety of innovative ways, many of them springing from new technologies. “There’s a range of things going on, from spot contracting and online auctions bidding out legal work to the creation of new kinds of relationships where some companies have a list of 50 law firms they use for everything, and it’s very hard to get on that list,” says Wilkins. “And once on it, companies make a lot of demands: that the law firms must be networked together, create virtual teams and so on. We know there’s a lot going on out there, but we don’t know the full extent of it or why it’s happening.”

The project is particularly focused on how companies measure the quality of legal services. “When they say, ‘We get the best,’ what do they mean?” Wilkins asks. “How much is driven by the relationship between a company’s general counsel and a law firm? Is it particular expertise they’re looking for, and how do they evaluate that?”

The research includes both qualitative and quantitative components. The center’s scholars have brought in a group of leading corporate counsel to help frame research questions and maximize “buy-in” from practitioners. Wilkins and Nanda, together with Coates and the center’s associate research director, Michele Beardslee ’02, are conducting in-depth interviews with corporate counsel, to be followed by a large-scale survey. The findings will be valuable to law firms seeking to sell their services, to law students looking to work in firms or corporations, and to companies searching for the best way to evaluate firms, they say.

Another major research project is “After the JD,” a first-of-its-kind national study of how young lawyers are creating careers. There are also smaller research projects under way, including one addressing the outsourcing of legal services to India (see story).

Indeed, the impact of “globalization”—a term frequently bandied about but not always understood—will inevitably permeate much of the research. “The center of gravity of the world’s economy is slowly but surely changing and is moving to Asia, and some other emerging economies,” says Cyril Shroff, managing partner of Amarchand & Mangaldas & Suresh A. Shroff & Co. in Mumbai, India, and a member of the center’s advisory board. “It is inconceivable that the legal support in these markets can only be provided by Western firms. There is an unprecedented opportunity for the growth of law firms in these other markets.”

Shroff hopes to help the center’s scholars analyze whether the business models adopted in Western firms are suitable for law firms in emerging markets—or “whether a unique Asian model for structuring law firms and legal services needs to evolve, consistent with the movement of economic power to the East.” Other subjects for inquiry will include “the ways in which law firms and legal professions can coordinate and collaborate globally and/or regionally,” and, conversely, the limits of global legal practice, he predicts. While some professions—accounting, for example—involve methods and practices that can be adopted worldwide (in effect, a universal language), law practice may never be able to achieve a similar level of universality, he says. While there may be many common denominators, there may be significant obstacles to the concept of a truly global legal profession. Exploring those limits will be part of the center’s focus, he hopes.

John R. Ettinger ’78, managing partner of Davis Polk & Wardwell, is similarly interested in the implications of globalization. “Seven or eight years ago I disagreed with the then prevailing viewpoint that we were inevitably heading toward a wave of transatlantic mergers, and I think that has proved to be correct,” he says. There are natural limits to the complete globalization of law firms, he explains, pointing out that many international transactions are not fundamentally cross-border and there is usually a single country nexus or governing law that prevails. He suspects that legal systems and the role of lawyers and law firms will continue to vary fundamentally from jurisdiction to jurisdiction. “I’m not saying globalization is not important,” Ettinger says. “I think most of the large firms will have a considerable global reach, but this is another case where there will be significant variation. Firms will have to ask themselves: Who are our clients? How much work do we do with financial institutions? They will have to figure out how to provide access to the best legal services in multiple jurisdictions. You can do it through a giant global firm, through highly integrated joint venture alliances or through smaller specialized foreign presences. Each model has its relative strengths and weaknesses.”

Curricular reform

In addition to the research projects, the center’s scholars also seek to make law school curricula more relevant to current issues in the legal profession. A generation ago, law students could expect to be well trained at whatever firm or organization they joined, whether private or public. “That’s no longer true, and so today, it’s no longer enough to teach people to think like lawyers,” says Wilkins. “We should continue to do that, but it’s not enough.”

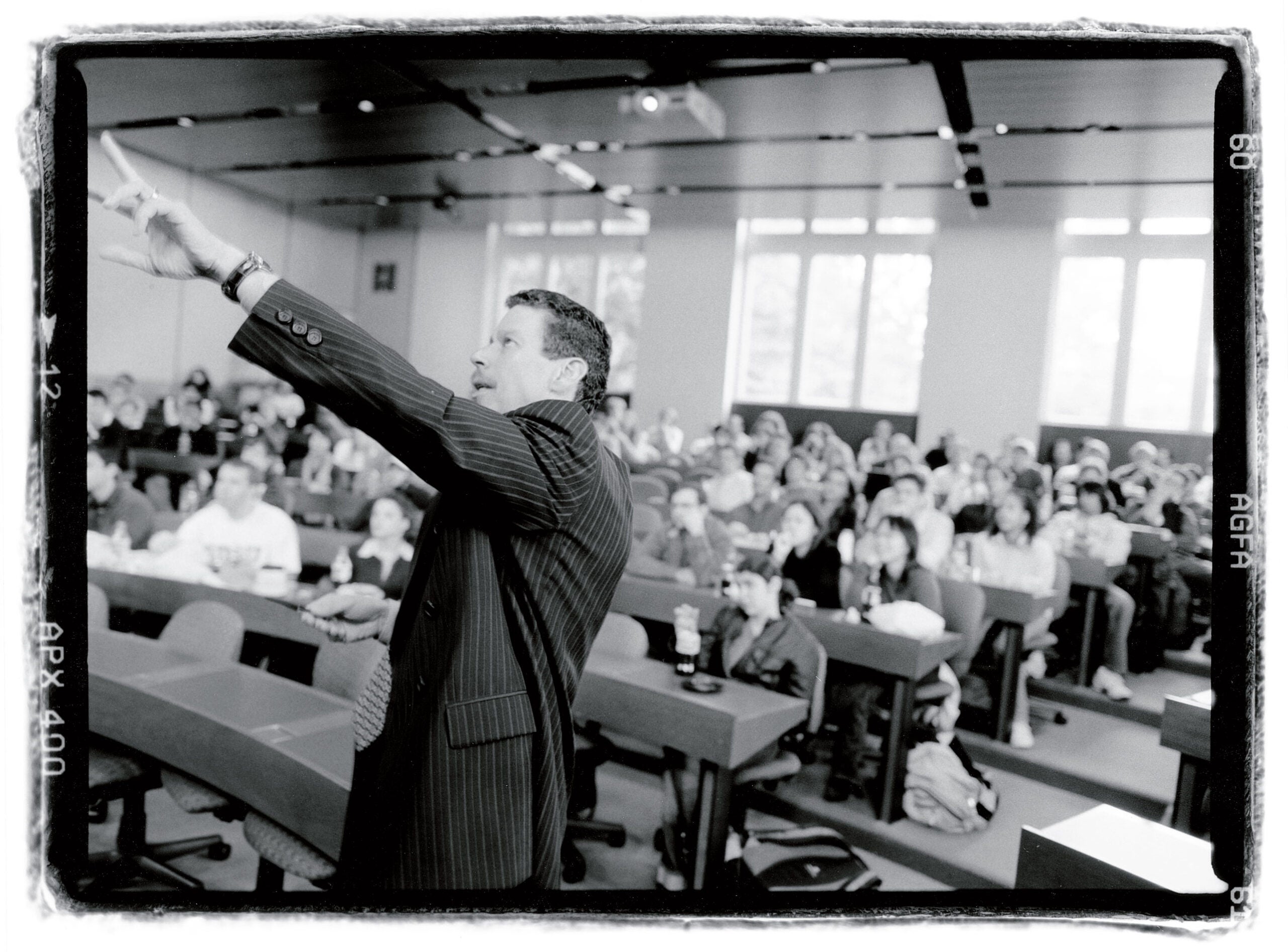

Nanda is particularly excited about a series of case studies the center is developing on law firms experiencing management challenges such as mergers. “We’re hoping to do many more, and we’re looking for firms willing to have case studies done on them,” he says. Similar to case studies used in business school courses, these real-world examples will be included in J.D. courses taught by the center’s faculty. The center will also bring in experts—like Heineman, who taught several classes last spring at both the law and business schools—to teach and advise students, and it has started a graduate fellowship program to encourage young scholars to address the problems of professional services firms.

The center is also launching an executive education program for law firm managers. The first session, titled “Leadership in Law Firms,” is scheduled for this spring, May 20 to 25, and will bring in top-level executives for a week of intensive classes on the challenges they face. It will be the first program of its kind at a law school.

[pull-content content=”

Guiding hands, from those with hands-on experience …

Professor Wilkins expects the Center on Lawyers and the Professional Services Industry will benefit greatly from the guidance of what he calls a “dream team advisory board”: Anthony Chase ’80(’81), chairman and CEO of ChaseCom; Kenneth Chenault ’77, chairman and CEO of American Express Co.; John F. Cogan Jr. ’52, of counsel at WilmerHale; John R. Ettinger ’78, managing partner of Davis Polk & Wardwell; Sean M. Healey ’87, president and CEO of Affiliated Managers Group; Robert D. Joffe ’67, presiding partner at Cravath, Swaine & Moore; Lewis Kaden ’67, vice chairman and chief administrative officer of Citigroup; Robert Katz ’72, senior director of Goldman Sachs & Co.; William Lewis Jr., managing director and co-chairman of investment banking at Lazard & Co.; Raymond J. McGuire ’83 (’84), global co-head of investment banking at Citigroup Global Markets; Adebayo O. Ogunlesi ’79, executive vice chairman and chief client officer at Credit Suisse; Paul N. Roth ’64, senior partner at Schulte Roth & Zabel; Cyril Shroff, managing partner of Amarchand & Mangaldas & Suresh A. Shroff & Co. in Mumbai, India; and Avy Stein ’80, co-founder and managing partner of Willis Stein & Partners.

Executive education for practitioners is one way of bridging the gap between practice and the academy. Bringing practitioners to the law school to share their real-world experience is another. In that vein, the Covington & Burling Distinguished Visitors Fund—endowed by contributions from Covington partners—is enabling distinguished members of the bench and bar to come to HLS and share some perspectives gained from practice with students and faculty. Current distinguished visitors include: Peter Barton Hutt ’59, senior counsel at Covington & Burling; Philip Burling ’69, a partner (retired) at Foley Hoag; James Flug ’63, former chief counsel for Sen. Edward M. Kennedy; Michael McConnell, a judge on the United States Court of Appeals for the 10th Circuit; and Peter Carfagna ’79, a partner at Calfee, Halter & Griswold in Cleveland.

Wilkins concedes that the center’s goals are ambitious and that its many initiatives are exciting yet daunting. Their unifying theme is the emphasis on closing the gap between the academy and practice. “We started the distinguished senior fellows project to bring leading practitioners of law firms and their expertise to the school,” he says. Heineman, the first fellow, “is as influential as any lawyer in his generation in pushing and shaping some of the changes we’re talking about. That’s the model—bringing in distinguished practitioners and having them engage in the full intellectual life of the school.” With students addressing case studies of real firms, practitioners sharing their experiences and academicians addressing ongoing issues, the cross-pollination of these two worlds will be mutually beneficial, he adds.