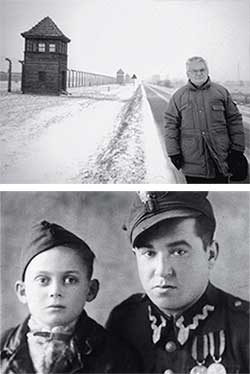

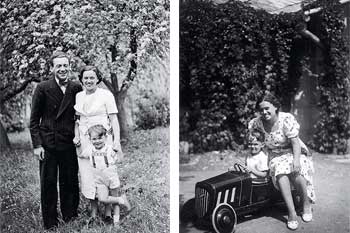

This summer Thomas Buergenthal LL.M. ’61 S.J.D. ’68 will begin writing a sequel to “A Lucky Child: A Memoir of Surviving Auschwitz as a Young Boy,” published in 2009. It is a harrowing, moving account of how Thomas, age 5, and his mother and father were trapped in Poland in 1939 after the invading Germans bombed their train as they fled toward England. Forced into a Jewish ghetto and work camps, four years later the Buergenthals were put on a train to the most feared destination of all: Auschwitz. There Thomas was separated from his parents—first his mother, Gerda, then his father, Mundek—and struggled by his wits and courage to survive alone.

As Germany neared defeat, Auschwitz was evacuated and Thomas joined the infamous death march and transport to the Sachsenhausen camp in Germany. At war’s end he walked out and was taken on as mascot of a Polish army unit, until one of the soldiers found a place for him at a Jewish orphanage. Finally, at age 12, he was reunited with his mother in Göttingen, Germany.

To this day Buergenthal cannot talk about that reunion. He learned his father had perished in Buchenwald, near the end of the war. He and his mother were among a handful of Jews remaining in Göttingen, and while he taught himself to forgive his oppressors, he knew Germany would never be home.

The sequel will pick up where “A Lucky Child” left off, at his arrival, alone, in New York Harbor at age 17. As he stood on deck, images of the Holocaust flashed in his thoughts. That day he knew: “My past would inspire my future and give it meaning.” He would “fight the ideologies of hate and of racial and religious superiority,” and he chose the law as his means. After earning his J.D. from New York University, he went to HLS, where his adviser and mentor was Louis B. Sohn LL.M. ’40 S.J.D. ’58., a staunch champion of the emergent United Nations. They co-wrote the first casebook on the protection of human rights, published in 1973.

“My Holocaust experience has had a very substantial impact on the human being I have become. … It equipped me to be a better human rights lawyer, if only because I understood, not only intellectually but also emotionally, what it is like to be a victim of human rights violations. I could, after all, feel it in my bones.”

—Thomas Buergenthal, “A Lucky Child: A Memoir of Surviving Auschwitz as a Young Boy”

In 1979 Buergenthal became one of the first seven judges elected to the Costa Rica-based Inter-American Court of Human Rights, when the region was a patchwork of nations ruled by military juntas and dictators wreaking terror with “disappearances” and torture of civilians. As he and colleagues scrambled to expose and punish the trampling of human rights, he remembers: “We invented everything; we all felt like we were John Marshalls.” He served for the maximum two terms, the only U.S. judge ever to sit on the court.

Buergenthal was elected in 2000 to the International Court of Justice in The Hague, serving a decade. In contrast to his hands-on work in the newly formed Inter-American Court, which brought him into contact with the victims of serious human rights violations, Buergenthal found The Hague court’s daily fare of interstate disputes less personally satisfying.

That there now exists an International Criminal Court is a very exciting development, says Buergenthal, who teaches international law and human rights on the faculty at George Washington University Law School, which he first joined in 1989. The ICC fills an important gap in bringing the worst offenders to justice, but it can try only very few people. And regional international human rights courts exist only in Europe, the Americas and Africa. Others are needed, he contends—in Asia, for example. Buergenthal also believes that serious thought should be given to the establishment of regional international criminal courts to supplement the jurisdiction of the ICC.

When Buergenthal was a child in mortal peril, “there was no such thing as international protection of human rights. I have always believed that if the institutions and laws we have now, no matter how weak, had existed in the 1930s, when Hitler was just getting started, they could have prevented much that happened later.”

The intractable worry for Buergenthal is something he witnessed over and over: the moral collapse of ordinary people. Why do some, like his parents, hold on to their integrity and moral compass, while others yield to brutishness and hate? The only effective deterrent is education, he believes, “and teaching children tolerance at the earliest age possible.”

By the time Thomas Buergenthal was free, the Nazis had killed his father, his grandparents, and Ucek and Zarenka, Jewish orphans who were like beloved little siblings. He had witnessed beatings, hangings, shootings, random cruelty. Yet he believes he was indeed a lucky child, as a fortuneteller foretold to his mother, just before Hitler overran Poland. That luck came in the form of bread loaves Czechs dropped from bridges, as his open train car packed with starving Jews passed beneath. It came from his resourceful parents, who taught him survival skills, such as hiding when inmates lined up for Dr. Mengele’s selections. And it came from friendships he made: the Polish doctor who tore up the card marking him for the gas chamber, the two boys who helped him stagger across a field on frostbitten toes to avoid execution. If not for all of them, Thomas Buergenthal would have died, in the darkest hours of his life. For them, he remembers, he teaches, he fights and writes on.