On Sept. 5, 2008, H. Rodgin Cohen ’68 took a telephone call that set in motion the most intense, high-stakes chapter of an already eventful career. The nation’s leading banking lawyer and chairman of Sullivan & Cromwell was summoned to Washington for emergency talks with then Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson, Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke and other government regulators. Cohen’s client Fannie Mae, the government-controlled mortgage loan buyer, was in danger of failing, reeling from the subprime mortgage debacle and skyrocketing foreclosures.

Within days, Cohen (known as “Rodge”) and his team had helped broker the deal that put Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac under federal conservatorship. But even as Cohen helped stave off one crisis, others erupted, with shocking speed. For the next five weeks he worked frantically with Wall Street and Washington leaders, counseling financial giants Lehman Brothers, AIG, Goldman Sachs, JP Morgan Chase, Wachovia, MUFG and others, as the realization grew that deep and unquantifiable risk riddled the U.S. financial system. The Dow Jones sank, credit markets froze, and by late September Paulson was calling for the $700 billion bailout known as the Troubled Asset Relief Program.

One year after the U.S. financial system’s excruciatingly close call, Cohen reflected on those “five weeks in hell,” warning signs that preceded that time, the state of the system today and dangers ahead.

About that frantic September, what stands out most, he said, is “the incredible, nonstop intensity” as the Fannie Mae/Freddie Mac rescue immediately morphed into the realization that Lehman Brothers was on the brink, “which then occupied everyone’s attention round the clock from Wednesday until Sunday, by which time AIG had become a major problem.” The ground beneath kept shifting, he said, adding, “So much was going on at once, it was impossible to figure out what sort of trouble would be next.”

Robert D. Joffe ’67, a partner at Cravath, Swaine & Moore, was also there when the shock waves began. “In late summer and early fall of 2008, Rodge represented Fannie Mae and I represented the independent directors of Fannie Mae,” Joffe recalled. “In a sea of waves, which was not always a pleasure, working with Rodge most certainly was.”

For Cohen, the worst moment was learning there would be no government rescue for his client Lehman Brothers, as he’d helped secure for his client Bear Stearns the previous March, and so a historic “icon” of American finance was left with no option but to file for bankruptcy. “I thought this was a horrible mistake,” said Cohen, “although it must be placed in the context of incredible pressure and many right decisions.”

“I had a meeting with government officials, in essence to say, ‘I assume if you let Lehman fail, you think you can develop a firebreak around that failure, so the fire won’t jump across. But the problem is, I don’t think you know how much dry tinder is on the other side, and there’s a hard wind blowing.’” The officials assured him the situation was under control. But, Cohen recalled, “I walked away from that meeting deeply concerned the government did not have it under control at all.”

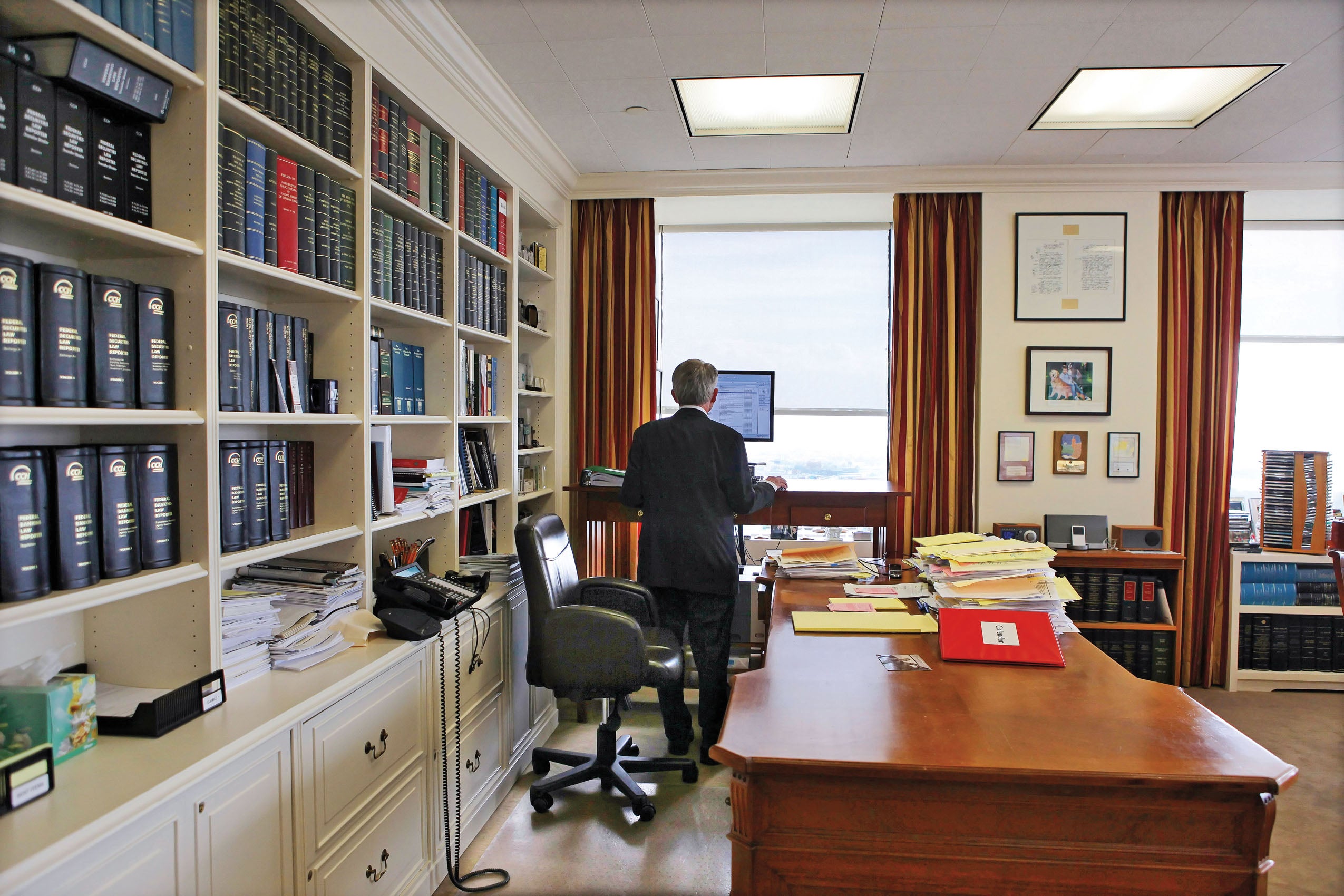

H. Rodgin Cohen ’68, in Grand Central Station, on his way to Sullivan & Cromwell, where he served as chairman from 2000, becoming senior chairman in 2010

Many would have quailed had they been aware of the powerful banking lawyer’s fears. Since the early 1970s, H. Rodgin Cohen has been a key player in helping build the financial system that almost failed. Said HLS Professor Howell Jackson ’82, “It’s hard to think of a major transaction or financial crisis where he didn’t play a leading role. He’s a terrific lawyer and an incomparable adviser.” Yet Cohen readily acknowledges that he too was stunned by the onslaught of fall 2008. The problem, he said, was that trouble came from all directions at once.

According to Cohen, three trends set the stage for the U.S. banking system in the 21st century. “Number one, clearly, was consolidation,” as the banking industry shifted from “single-city, at most single-state-based” banks to national then global institutions. The second trend was the steady elimination of barriers separating banks from other financial services, from the Bank Holding Company Act Amendments of 1970 to the Financial Services Modernization Act of 1999 that allowed bank holding companies to diversify into securities and insurance. The third trend was “incredible innovation in the banking industry itself,” which toppled the banker’s long-standing conservative motto of “3-6-3: Borrow at 3 percent, lend it out at 6 percent, on the golf course at 3.” One of the great ironies, Cohen noted, “is that a number of products and policies were devised to diversify risk, which is good, but these also mask risk and make it opaque.”

Cohen’s own confidence in the financial system’s stability was shaken during 2005 and 2006, when bank regulators proposed new guidelines on residential real estate lending. Working with banks to prepare their response, “I became aware of the deterioration in underwriting standards for residential real estate lending,” he said. Another warning sign came in August 2007, when the major mortgage lender Countrywide almost collapsed. “In this and each subsequent crisis, two or three people were largely responsible for avoiding disaster,” he explained. In this case, Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner, BNY Mellon CEO Bob Kelly and JPMorgan Chase Chief Executive Jim Dimon “stepped up and did the right thing to keep Countrywide afloat. But when I saw how close we’d come to failure, it was clear how fragile the system had become.”

What ultimately triggered the 2008 meltdown? The major culprit, Cohen believes, was excessive leveraging on every level—individual, corporate and government. “But even that would not have been a problem without numerous contributing factors,” such as excessive risk at individual institutions and lax lending standards, he said, “which helps explain why government and business and the private sector failed to see what was coming much earlier.” Clearly, there was not enough scrutiny. “You can blame government officials for that,” Cohen said, “but they didn’t make these loans. Nobody escapes blame.”

Cohen shared his views with the easy command of someone who has spent his entire career intensely engaged with his specialty. A Charleston, W.V., native, whose father owned a chain of drugstores and mother was active in local philanthropy, Cohen attended Harvard College and then went directly to Harvard Law School, the only member of his family he can think of, apart from a cousin, to pursue law as a profession.

Yet as a law student Cohen had no particular interest in financial systems. “Banking law chose me,” he said, when, after serving two years in the Army, embarking on his new job as a general practitioner at Sullivan & Cromwell, he was invited to shift over to the banking section, then in flux. Protesting that he knew nothing about banking, the fledgling associate was told, “Don’t worry. You’ll pick it up.”

So he did, at a breakneck pace, his career unfolding in tandem with massive shifts in the financial system, including the M&A boom and the rise of globalization. He started out in the 1970s, a decade of “great uncertainty,” with the slumping U.S. economy and a freezing of the financial system around the world during the Herstatt crisis, when one of Germany’s landmark banks collapsed. He regularly traversed the tightrope of high-stakes crises, from his work on resolving the 1974 bankruptcy of the Franklin National Bank, at that time the largest bank failure in U.S. history, to his involvement in the 1981 bank negotiations unfreezing Iranian assets that led to the freeing of American hostages held in captivity for 444 days. He helped rally the Wall Street community in the aftermath of the Sept. 11 attacks, and subsequently worked for two years with banks around the world to close a major loophole for terrorist funding.

In the aftermath of the 2008 crisis, “we’re all trying to figure out what went wrong—not to assess blame but to prevent any recurrence,” he said. “We’d lived through serious crises in the past 30 years. Each time we surmounted them” without risking a true financial collapse. “But this time that didn’t happen.”

Today, Cohen said, the “danger of financial contagion remains very real.” Government agencies charged with oversight “do not have the necessary information to deal with the potential of great risk in the system.” And “risk control systems are neither adequate at many financial institutions nor sufficiently monitored by the regulators.” The biggest threat, he said, is that if customers and depositors are no longer able to evaluate the viability of a financial institution, “they will flee.”

Cohen walking his dog, Bacall (named after the actress Lauren), near his home in Irvington, N.Y.

He emphasized concern for the nation’s small and mid-size banks, citing projections that a thousand of them could fail. “We can’t quantify how much risk that would create,” said Cohen. “We need to reduce that number.” His practice has shifted as he helps smaller institutions through the same array of life-threatening problems that his large institutional clients have resolved—he put it understatedly—“one way or another.”

After the tumultuous cycle of resignations, ousters, and upheaval on Wall Street and a presidential transition, Cohen has confidence in the current leaders of the nation’s major financial institutions, and particularly in Timothy Geithner and Ben Bernanke of the government’s financial sector.

In June, President Barack Obama ’91 released proposals for “a sweeping overhaul of the financial regulatory system, a transformation on a scale not seen since the reforms that followed the Great Depression.” Cohen concurred that nothing less is needed. “President Obama’s clarion call is correct,” he said.

The proposed federal financial reforms include tougher regulation of the derivatives market, a requirement that credit-default swaps be traded through clearinghouses and the creation of a national consumer financial protection agency.

“Consumers were ill-served; our regulatory system didn’t work,” Cohen said, “but I question whether we need a new authority but rather a reinforcement” of existing regulatory authorities. One clear need, he said, is to have all the states represented. However, he is against a provision that would permit states to enact their own consumer protection laws on top of those set by the federal government. Calling the proposal “ill-conceived and inconsistent,” and the most damaging from the banking industry’s perspective, Cohen pointed out that since McCulloch v. Maryland of 1819, “we’ve had a national banking system with uniform national rules.” Instituting state-by-state rules would give each state “total enforcement powers.” One would never know for certain “which regulator would challenge what.”

Whatever shortcomings Cohen perceives, the federal reform package is vital not only “to have the ability to deal with problems, but also to help restore confidence,” he said. Nevertheless, he warned, “ultimately, unemployment has to peak to begin a recovery. Our financial system has built-in shock absorbers, but nothing can overcome a bad economy.”

When asked how he escapes the nonstop, sometimes crushing demands of his work, Cohen said he likes to take his dog on long rambles. He and his wife are devotees of the theater and regularly attend performances by the New York Philharmonic and Westchester Philharmonic. Cohen also enjoys sitting down at the piano. Is it pure chance, in a year of guiding clients through shock and tumult, that he found himself drawn from his familiar Broadway repertoire to a new interest in mastering the chord changes of rock and roll?