In October, the Supreme Court heard a challenge to the constitutionality of a law extending copyright by 20 years. But the question posed by the case, says Assistant Professor Jonathan Zittrain ’95, is whether copyright can last forever. How is a limit still a limit, he asks, when Congress extends it again and again?

In 1999, online publisher Eric Eldred protested the 1998 Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act, which lengthened the term of current and future copyright from 50 to 70 years beyond the life of the author. The law delayed the entrance into public domain of a wealth of works–from Robert Frost poems to Sherwood Anderson short stories–that Eldred wanted to make available on his Web site. And it wasn’t only classics that were affected, but a slew of movies, songs and books for which the copyright holder is unknown. The Harvard Law School Berkman Center for Internet & Society took up the challenge. (In January, the Supreme Court ruled 7-2 to uphold the extension.)

Zittrain says people who are used to the wide open spaces of the Web are suddenly running up against the complex constraints of copyright law.

“Thanks to the Internet, we’re in the midst right now of a sort of cultural reassessment of the meaning of copyright,” said Zittrain, co-counsel on the case and co-director of the Berkman Center along with Professors Charles Nesson ’63 and Terry Fisher ’82.

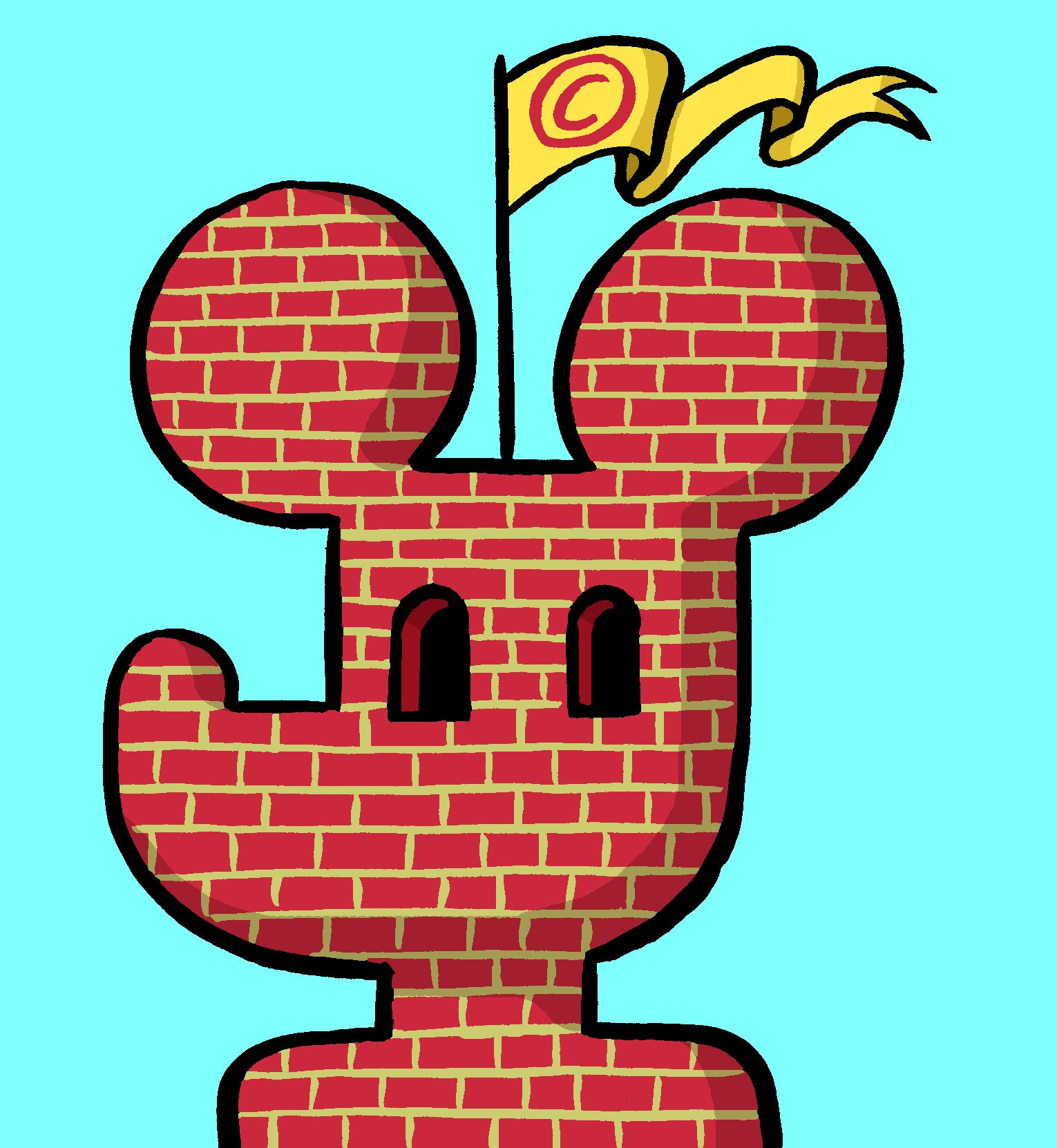

Eldred v. Ashcroft captured the sort of public attention that issues of copyright have rarely commanded. Amici briefs stacked up on both sides. Authors such as Ursula Le Guin and Charles Baxter opposed the law. Media interests, including Disney, were strong supporters. The first movie featuring Mickey Mouse was among the works that would have entered into the public domain without the law, and “Free Mickey” became the rallying cry of the anti-extension forces.

But not everyone at the Berkman Center agrees with them. Professor Arthur Miller ’58, who wrote an amicus brief in favor of the extension, contends that Congress has adjusted the term of copyright over the years for good reason. It has taken into account increased longevity and a desire to bring American law in sync with the rest of the world; by 1998, for example, the European Union provided copyright protection for 70 years beyond the life of the author. Historically, benefits have extended to the family of the creator, he says, providing greater incentive for artists to create in the first place. Extended terms, he believes, guarantee the future dissemination of the work and, by stimulating derivative industries, such as movies and television, fulfill the purpose of copyright according to the applicable clause of the Constitution.

During oral arguments, the focus was on that clause, which states that Congress has the power to grant copyright “for limited times” and in order “to promote the progress of science and useful arts.”

Arguing for the plaintiff, Stanford Law School Professor Lawrence Lessig, who is a former HLS and Berkman Center faculty member, made the case that Congress’ repeated extensions (11 over the past 40 years) effectively make copyright limitless. The government argued that the same clause of the Constitution leaves the question of limits up to Congress.

Some of the justices saw a problem with the law but also with the Court’s remedying it. “I can find a lot of fault with what Congress did here,” said Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, “but does it violate the Constitution?” Others questioned whether striking down the act might invalidate earlier extensions, such as the 1976 law that transformed the terms of copyright. Justice Stephen Breyer ’64 asked, “If the latter is unconstitutional on your theory, how could the former not be? And if the former is, the chaos that would ensue would be horrendous.”

Zittrain says he fears supporters of the act will present the same arguments to Congress in 20 years for the next copyright extension. Copyright protection that was initially 14 to 28 years can now last well over 100. “Because so few things have entered the public domain in our lifetimes,” Zittrain said, “people get used to thinking that once something is copyrighted, it’s always copyrighted. And that was exactly not the process the framers envisioned of a limited-time monopoly.”

Petitioners pointed to the long tradition of using earlier works as the inspiration for new ones–Leonard Bernstein’s “West Side Story” as a retelling of “Romeo and Juliet,” for example. Disney itself, they said, has used public domain stories as the kernel for movies such as “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs” and “Cinderella.”

If Disney could do it, says Zittrain, then the rest of us should have the same chance.