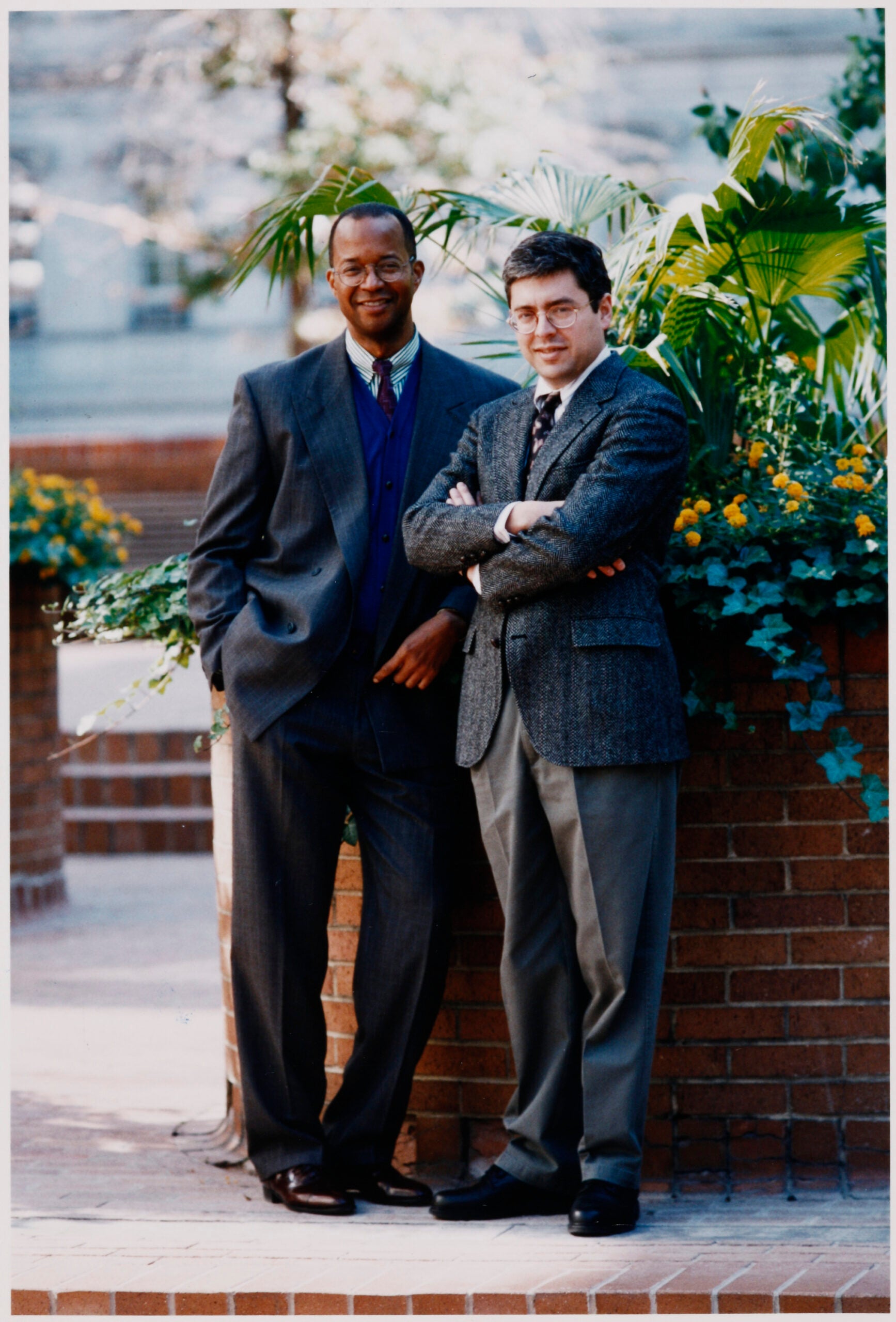

How two HLS roommates became author and subject

Lawrence Mungin and Paul Barrett

From childhood Lawrence Mungin ’86 excelled in whatever pursuit he chose, with a single-minded drive that took him from a Queens housing project to Harvard College and Harvard Law School. His corporate law career was progressing nicely when he took a new job in 1992 in the Washington, D.C. office of Chicago-based Katten Muchin & Zavis. It was there that the black lawyer’s career unraveled under conditions that led him to sue his firm for racial discrimination.

The legal complexities and elite milieu of Mungin’s lawsuit made headlines, and attracted the professional curiosity of his first-year HLS roommate, Paul Barrett ’87, then a Wall Street Journal reporter based in D.C. While Mungin testified in federal court about his low-level work assignments, reduced billing rate, failure to be considered for promotion, and other insulting treatment by his firm, Barrett was listening and taking notes.

Barrett decided Mungin’s legal battle was the ideal subject for the book he wanted to write, and Mungin agreed to cooperate, despite misgivings. So began an unusual dialogue on the ambiguities of racism and the damage done to an HLS graduate seemingly bound for unstoppable success.

Shortly before the January publication of The Good Black: A True Story of Race in America (Dutton), Bulletin Senior Editor Julia Collins talked with the author and his subject.

Larry and Paul Meet at Harvard College

Larry Mungin and Paul Barrett met late in their Harvard College careers, while both resided at Lowell House. Larry was four years older, having taken a leave to join the Navy, where he won awards as a Russian code-breaker.

After the casual acquaintances discovered they had HLS applications in common, Paul and Larry agreed to become 1L roommates. Hailing from a mostly white, middle-class New Jersey suburb, Paul admits experiencing a “small guilty thrill” at the idea of having a friend who was black. Skin color didn’t signify to Larry, however, who had always eschewed racial identity politics and socializing. “I wanted someone distinctive for a roommate,” he says, “someone I could respect and learn from.” As president of the Crimson, Paul fit the bill.

During the nine months they shared a Hastings Hall suite, Larry and Paul often talked about their dramatically different upbringings. Larry was far more selective in his confidences than Paul ever knew, however. Only when Paul turned author, and Larry became his subject, did he learn about Larry’s many experiences of racial bias and the pressure he felt under to be “the good black.”

In his second year Paul made the Law Review and got a job offer, but had no interest in legal practice. He quit law school and went to work for the Washington Monthly. Later he completed his HLS degree and became a journalist specializing in legal issues.

Larry meanwhile enjoyed his classes, particularly Criminal Law with Alan Dershowitz, and anticipated a rewarding corporate law practice. Though his grades didn’t land him on the Review, they put him in the respectable middle of the pack and made him an attractive job candidate.

The Roommates Cross Paths Again

After graduation Larry and Paul went their separate ways. They exchanged occasional postcards and letters, informing each other of major events: Paul’s big stories, Larry’s job jumps from the Houston office of Weil, Gotshal & Manges to Atlanta’s Powell, Goldstein, Frazer & Murphy, and on to the latter’s D.C. office.

It was in D.C. that their paths crossed again, more than six years after HLS. Paul had moved to the city from the Wall Street Journal’s Philadelphia office and was covering the Supreme Court.

The lawyer and the journalist began meeting for occasional lunches. In 1992, Larry told Paul he had decided to leave Powell, Goldstein and join Katten Muchin as a senior associate, buoyed by the prospect of higher pay, challenging bankruptcy work, and partnership consideration. “He seemed optimistic and upbeat,” Paul says.

In 1993, however, Larry’s lunchtime reports on his job grew troubled and anxious. Paul chalked it up to a temporary rough patch. Then Larry stunned him by confiding that things were going very badly at Katten Muchin. He asked whether Paul could recommend a lawyer for him to consult. Paul didn’t realize Larry had a racial discrimination suit in mind, and referred him to an attorney who represented unhappy corporate executives. “A reason Paul misunderstood,” says Larry, “is that I was reluctant to say, ‘Oh my god, I’m a victim of racism.’ I would have been uncomfortable saying the r-word.”

Larry’s Lawsuit

Larry filed his suit against Katten Muchin in the fall of 1994, represented by a minority-owned firm he had read about.

“From then on, I began to listen a lot closer,” Paul says.

“Paul took a wait-and-see attitude,” says Larry. “I knew that I, and the facts, had to stand alone.” He prepared diligently with his attorneys, aware that, win or lose, his case would cost him dearly.

The Supreme Court building isn’t far from the federal trial court in D.C. When Larry’s case came to trial, “I was able to sneak away from my job and watch in the courtroom,” says Paul. “But I wasn’t there as Larry’s cheering section. I’m a newspaper reporter.”

“I thought Paul was out there for self-serving reasons and if it gave me moral support, great,” says Larry.

During the weeklong trial, Katten Muchin’s attorneys asserted that Larry’s ordeal was the result of equal-opportunity firm mismanagement. While Larry had not suffered overt racist acts, his lawyer, Abbey Hairston, argued that Katten Muchin, a mostly white firm, had steadily neglected and passed over him because of race.

On March 22, 1996, the Washington jurors—seven blacks and one white—unanimously awarded Lawrence Mungin $2.5 million in compensatory and punitive damages.

“When the verdict was read—‘yes,’ ‘yes,’ ‘yes’—I realized, ‘oh my god, this is a huge event.’ I don’t remember another case of this kind won by a black lawyer [plaintiff],” says Paul.

Larry was unmoved by the media hoopla. What mattered to him was the courtroom validation of what he’d suffered. “I had paid a heavy price to get there. I felt the jury and judge understood what I was saying.”

Paul’s Book

Soon after the jury trial, Paul told his former roommate he intended to write a book on the case. The news surprised, flattered, and pained Larry. He knew Paul would insist on journalistic independence and refuse to accept his views at face value on anything. “Paul said he would write the book whether I’d cooperate or not.” It was particularly hard for Larry to be questioned on sensitive race issues by someone not from his background. “While Paul knew me, he didn’t know anything about my views on race.”

Paul and Larry started getting together on weekends for long discussions that focused initially on Larry’s experiences as a lawyer, then spread into all corners of his life. “At times our conversations were invigorating and satisfying, at others, tense and even wounding,” Paul says. “I began, at last, to get a full picture of the man.”

Paul had considered Larry thoroughly integrated in society, ready to cruise ahead in a law firm. “But it turns out the guy is more complicated than that. I was typecasting him. The many racist slights and emotional bruises, the awkward frustrations he’d faced” as a minority—were revelations to Paul.

Larry was ambivalent about sharing certain kinds of information, particularly concerning his father, Lawrence Lucas Mungin, Jr. When Larry was a child, his mother had ordered her unreliable husband out of the house, and proceeded to raise her family single-handedly, but at great personal cost.

“And he got it,” says Larry.

Just before Christmas in 1997, Paul shoved a box in Larry’s hand. Not a Christmas gift, which Larry jokes would have been a nice surprise, but rather the completed manuscript. “I started reading it and couldn’t put it down,” says Larry. “There were painful parts, but it was as accurate as it could be. It was interesting to read a white person’s account of the trial. Paul didn’t cut me any slack, but he treated me with respect and made me a three-dimensional person.”

“Mungin sat on a low couch in [Katten Muchin partner] Sergi’s large office, next to a pile of legal documents. His host got a few sheets of paper from his desk and sat down in an adjacent chair. Files, folders, and bound financing documents were strewn everywhere.

‘I’m worried,’ Mungin began, ‘and I can’t get anyone in either Chicago or Washington to give me and explanation’ as to why he hadn’t been evaluated and hadn’t received a raise.

Sergi responded in a mild, apologetic tone. ‘You fell beneath the cracks,’ he said. ‘I’m sorry.'”

From The Good Black (Dutton, 1999)

Chapter 22 and Larry’s Epilogue

The final chapter of Paul’s book recounts the final chapter of Larry’s case: On July 8, 1997, three D.C. Circuit judges voted 2 to 1 to reverse his trial win. The $2.5 million in damages evaporated, along with Larry’s future in corporate law.

As Paul’s book reports, Larry’s case drew attention to a disturbing racial dissonance, with black lawyers Paul questioned generally relating to Larry’s version of the Katten Muchin debacle, while white lawyers insisted that all young associates, white or black, are equally abused by law firms today.

At present, Larry works as a contract lawyer around Washington and earns a modest hourly rate. He has no regrets about the lawsuit. “People may find it hard to believe, but I really don’t think about it. For me, it was most important to have my day in court. While I don’t have the law partner or CEO option now, I can certainly make myself happy. I’m definitely planning to retire to coastal South Carolina.” There he will continue recording family history. In the midst of his legal ordeal, Larry renewed ties to his father, who has since died, and their relatives, descendants of the Gullahs, former slaves with West Indian roots and a distinctive culture, language, and spiritual beliefs.

Says Larry of the old roommate who told his story: “Even when I decided to cooperate, I was always angry at Paul. A couple of times I exploded, but hoped he knew it came with the territory, with him talking to all the people in my life.” Now that the book is written, he says, “I’m relieved my faith in Paul was not in vain. Despite our differences, we really came together on this.”