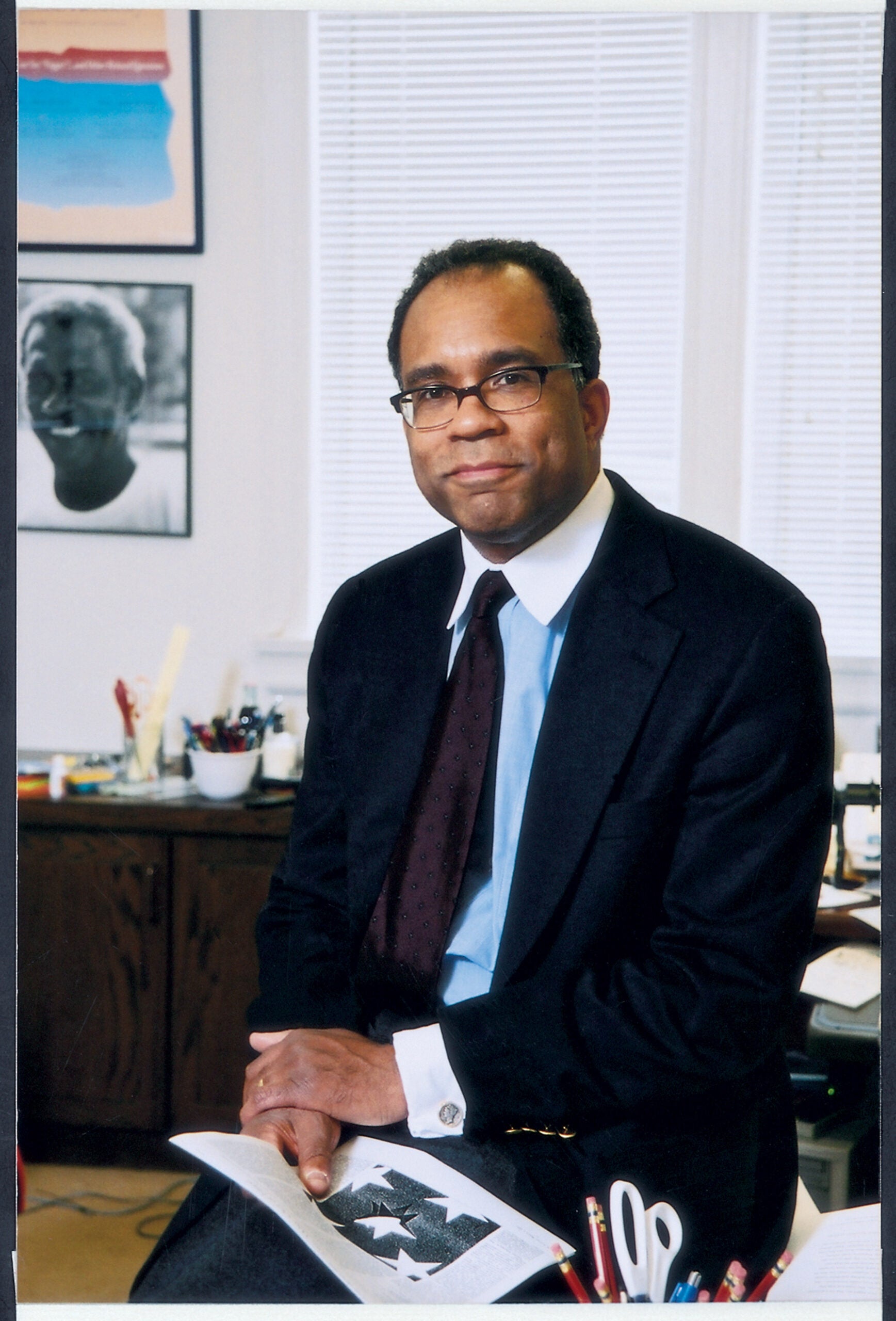

A hypothetical: A reporter is going to interview Professor Randall Kennedy. The reporter says to a group of coworkers: “That is one righteous nigger.” A colleague complains. The reporter, whose intent was to compliment the professor, is fired for using grossly offensive language.

Kennedy enjoys the hypothetical, repeats the phrase “righteous nigger,” smiles, says he’ll remember it. He says that he would defend the reporter. He would also defend the right to think about the word nigger, play with its many meanings, even, in the right context, say it.

After all, he has literally written the book on it.

In Nigger: The Strange Career of a Troublesome Word (Pantheon Books, 2002), Kennedy examines the legal and social history of the “paradigmatic slur,” as he calls it, a word that has caused such hurt and anger, a word that many people refuse to ever speak in any context. It is a word that was regularly hurled at him in hatred when he was a child in South Carolina and is offered to him in friendship today. That seeming contradiction interests him, led him to do a Lexis search that unearthed thousands of legal cases in which the word was central, and motivated him to write a book that has caused a firestorm of media attention and some consternation.

“I have invested energy in this endeavor because nigger is a key word in the lexicon of race relations and thus an important term in American politics,” Kennedy writes. “To be ignorant of its meaning and effects is to make oneself vulnerable to all manner of perils, including the loss of a job, a reputation, a friend, even one’s life.”

The book outlines the derivation and evolution of the word and its use by bigots, comedians, rappers, writers, and politicians, among others. Kennedy argues that “[w]hat should matter is the context in which the word is spoken–the speaker’s aims, effects, alternatives.” In a section called “Nigger in Court,” he details four types of cases: justice officials who have used the word; people who contend they were provoked to violence by the use of the word; people who sue after being called the word; and judges who must decide whether to tell a jury that a witness or litigant used the word.

And Kennedy addresses what he calls the “pitfalls in fighting nigger,” including the 1993 case of a white basketball coach at Central Michigan University who hears black team members urge each other to play better and tougher, to play, they say, like a nigger. He asks permission to use the word too. His players agree. But the administration doesn’t. The coach is eventually fired.

According to Kennedy, the coach may have been imprudent and reckless for using the word, just as anyone would be in a situation where the word could be misconstrued. The coach deserves censure and should not say it again to his players or at work. But the coach should not be fired, he says.

“I want there to be a thoughtful exploration and not a response as if this was simple as could be,” said Kennedy. “Not a response as if, well, everybody knows that’s a slur and that’s all there is to it. No, actually this gets rather complicated.”

It does when a person who is black greets a black friend with a hug and says, “Hello, my nigger.” It does when black comedian Chris Rock says that he loves blacks but hates niggers, and his audience, mostly black, roars with approval. It gets complicated when Kennedy is asked if a murderer who, before the crime, says, “I’m going to kill you, nigger,” should receive a harsher penalty than a murderer who, under the same circumstances, says only, “I’m going to kill you.” Kennedy is simply not sure of the answer.

But he is sure that he is going to keep asking questions, even if they make people uncomfortable. His book certainly does that. Some critics have accused Kennedy of exploiting the word, and of giving bigots a free pass to use it. Eradicationists, as he calls them, want to wipe the word out of the language. Some people who want to read the book simply can’t bring themselves to ask for it in bookstores. Even on campus, in an announcement that the Black Law Students Association will host Kennedy for a talk about his book, the title is conspicuously absent.

In fact, Kennedy wants the word nigger to make people uncomfortable. The word as racial insult and threat should be stigmatized, he says. “But I’m certainly not offended when I encounter nigger as affection, nigger as gesture of solidarity,” he said.

For the author of Race, Crime, and the Law, the response to his latest book serves as another chapter in the history of the word and of race relations. He plans to write a chapter on the reaction for the paperback edition. But for bad and for good, Kennedy says, that will not close the book on nigger.

“The word that Randall Kennedy catalogued in his book roiled the HLS campus this spring when a student posted a course outline that included a shortened version of the racial epithet. The student apologized. Later, flyers containing racist language claiming to test the limits of free speech were placed in campus mailboxes. Kennedy moderated an on-campus discussion about the incidents, and the HLS administration condemned the intolerant acts and met with concerned students. For a copy of Dean Clark%SQUOTE%s response to the incidents, e-mail news@law.harvard.edu.”