Terry Franklin ’89, a trusts and estates litigator, knows the importance of wills to those left behind. Recently he has focused on a will executed 170 years ago with enormous bearing on his ancestors’ survival and his own existence.

Franklin family lore tells of Grannie Lucie, the “property” of a white man named John Sutton. They were Franklin’s great-great-great-great-grandparents. Franklin had seen an abstract of Sutton’s will, which stipulated that his “mulatto slave Lucie” and her eight children and six grandchildren were to be freed after his death. What Franklin did not know, and what gnawed at him, was whether Sutton also had a white wife and children.

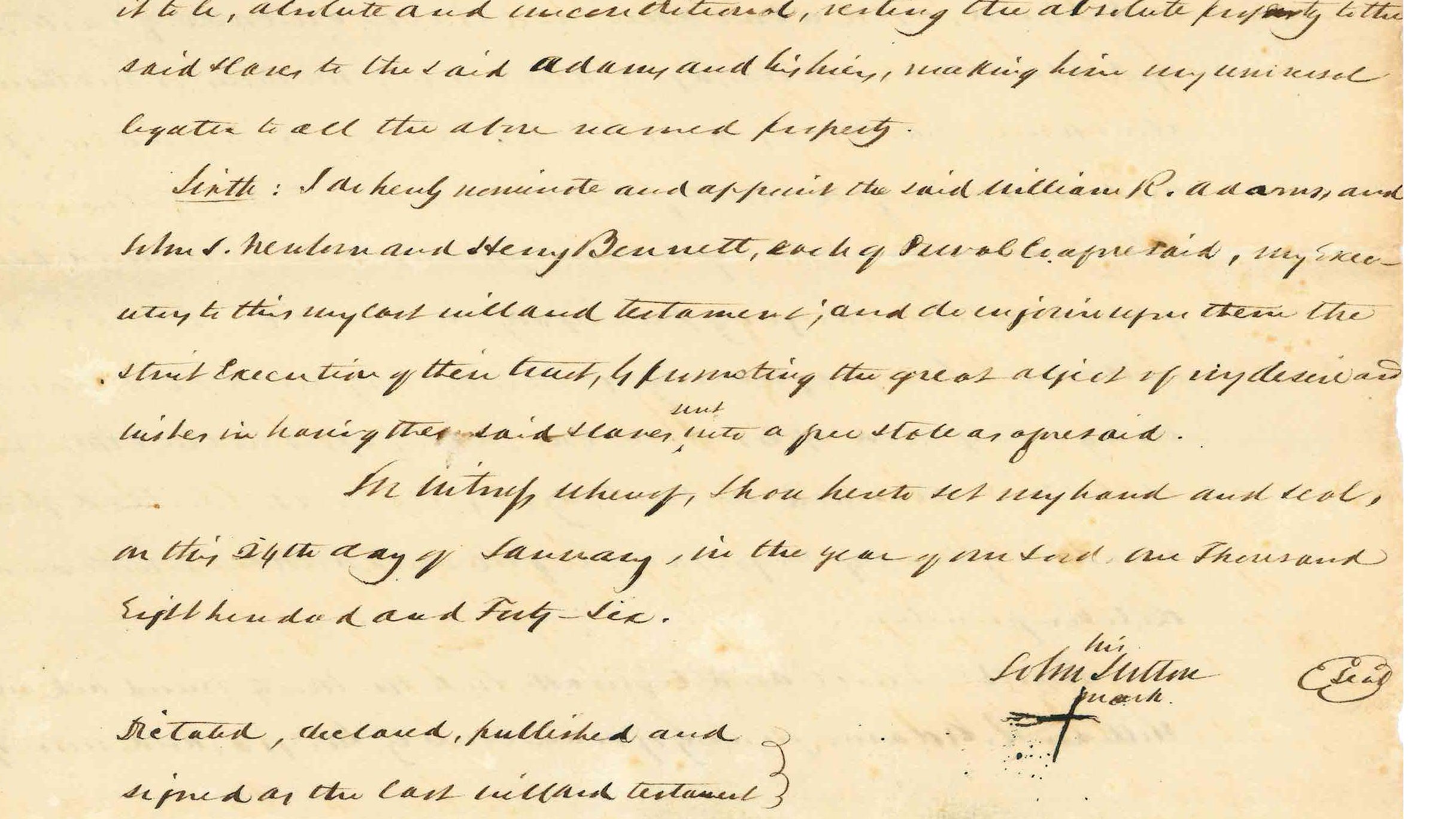

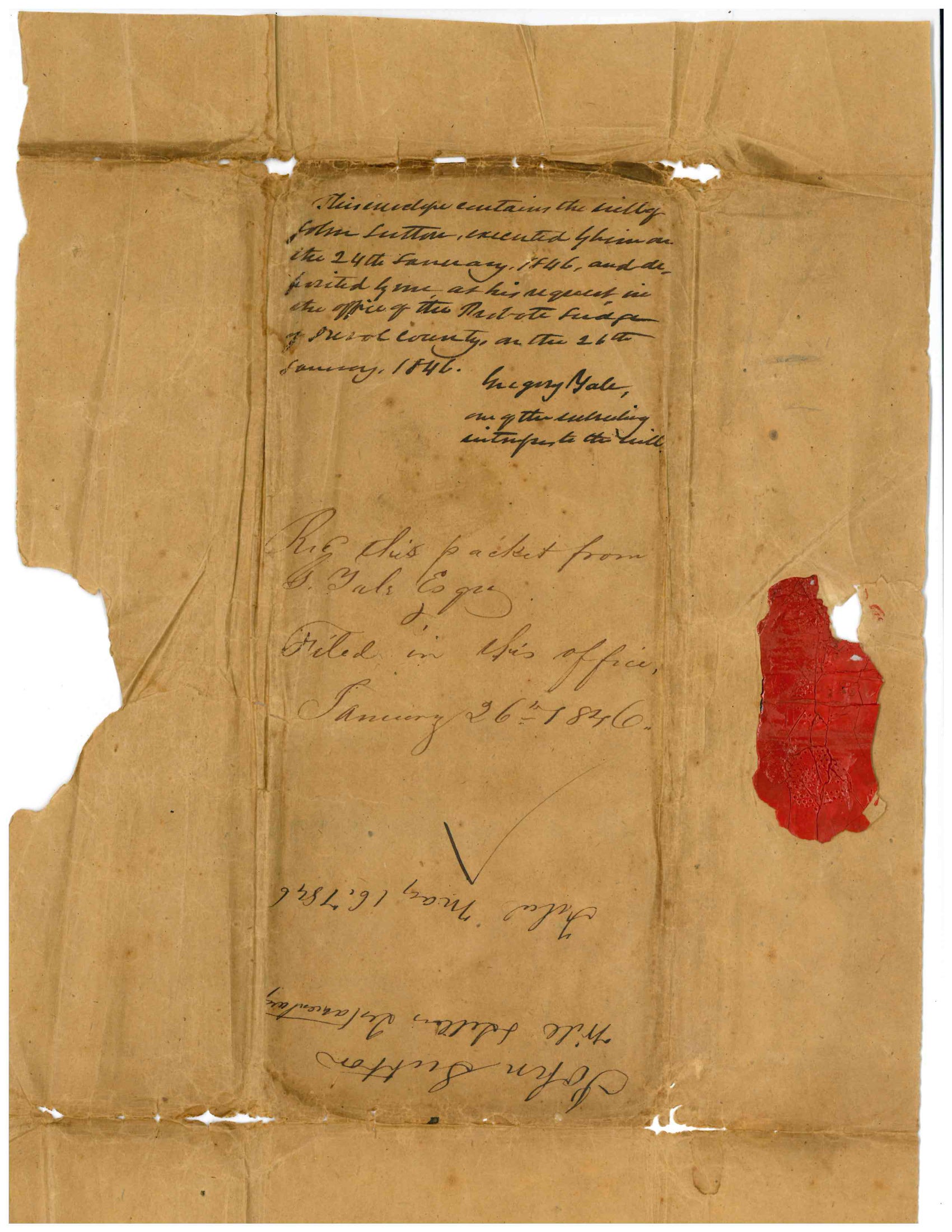

He traced the will to Duval County, Florida, and asked a clerk to send him images of the full document—handwritten pages marked with an “X” by Sutton, who died in 1846.

When he read the will, he saw it listed the livestock to be sold off to fund the journey of Lucie and the children to a state or foreign country “where they and their children could live free forever.” There was no mention of a wife.

Franklin is well aware of the perversity and enduring evil of slavery, but he wanted to believe that what developed between Lucie and Sutton was a relationship.

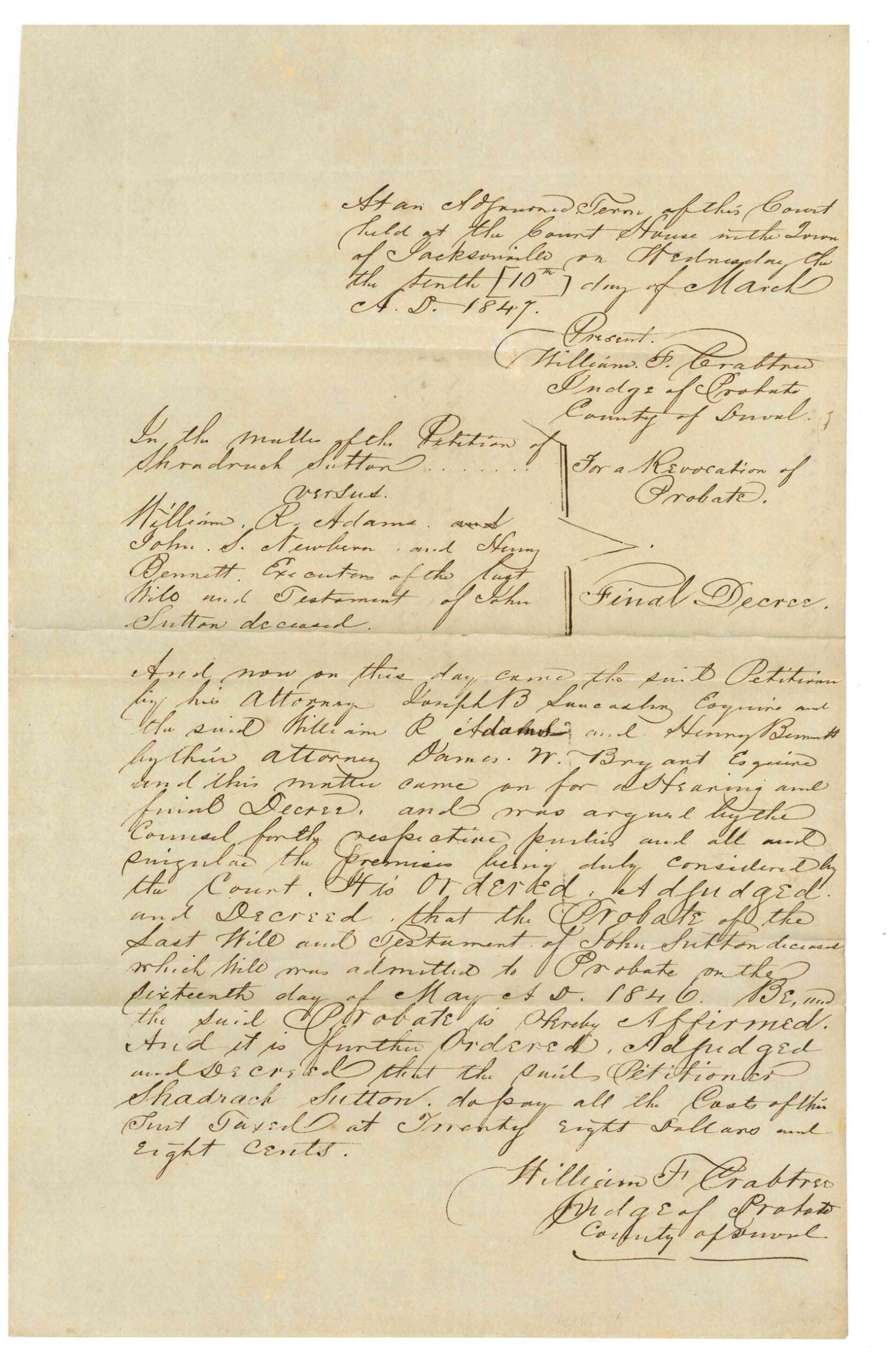

It became clear to him that it was a story he wanted to tell. He published several related articles, including in the ABA’s Probate & Property magazine. He also began writing a novel. “People always say, ‘Write what you know,’” Franklin says. Contested wills come up a lot in his work, so in the novel, he invented a brother for Sutton named Eustis, who challenges the will.

As Franklin imagined this story, he wanted to hold the actual document in his hands. During a business trip, he took a long detour to Duval County. When the clerk handed him the folder, he saw that in addition to the will, it contained other handwritten pages. He soon realized he was reading a trial transcript. As it turns out, there had been a will contest brought by one of John Sutton’s brothers, Shadrack.

The transcript also provided clues about Lucie and Sutton’s relationship. Franklin learned that Sutton had lived in Georgia, and before writing the will, he had moved his household to Florida, thinking it was a state that would allow him to emancipate Lucie and her children. But once he arrived, he learned this wasn’t so.

Franklin was also struck by the lawyer’s testimony that when he came to make the will with Sutton, “his family” invited him to eat. “He described them as family,” says Franklin, “not slaveholder and slaves.” It was one thing to have children with a slave. It was another to set up a household with her, which is what Franklin believes Sutton did.

Toward the end of his life, Sutton took all the precautions he could to protect the woman he loved, says Franklin. Soon after his death, Lucie and her children made their way to freedom—from Florida to Illinois, where Franklin grew up.

Franklin has now spoken about his discoveries to audiences from children in his daughters’ school to lawyers at conferences.

With lawyers, he shares details such as a provision that if the will were for any reason found invalid, ownership of Lucie and the children would be transferred to the executor, William Adams, who Franklin suspects was Lucie’s white half-brother, who would have freed them.

Beyond the ties of ancestry, Franklin makes another connection between this story and his own. He fell in love with and married a classmate at HLS, and together they have two daughters. But when he came out as a gay man six years ago and they split up, he realized that for much of his life he had forced himself to be something he wasn’t. Franklin sees a connection between the social strictures, laws, and expectations that oppressed Sutton and Lucie’s relationship, and those that had constrained his own world.

In addition to his legal practice, Franklin continues to work on the novel and a related screenplay and to speak at conferences about his ancestors’ story. People seem to relate to it on a deep level. For Franklin, it has “breathed new life into everything.”