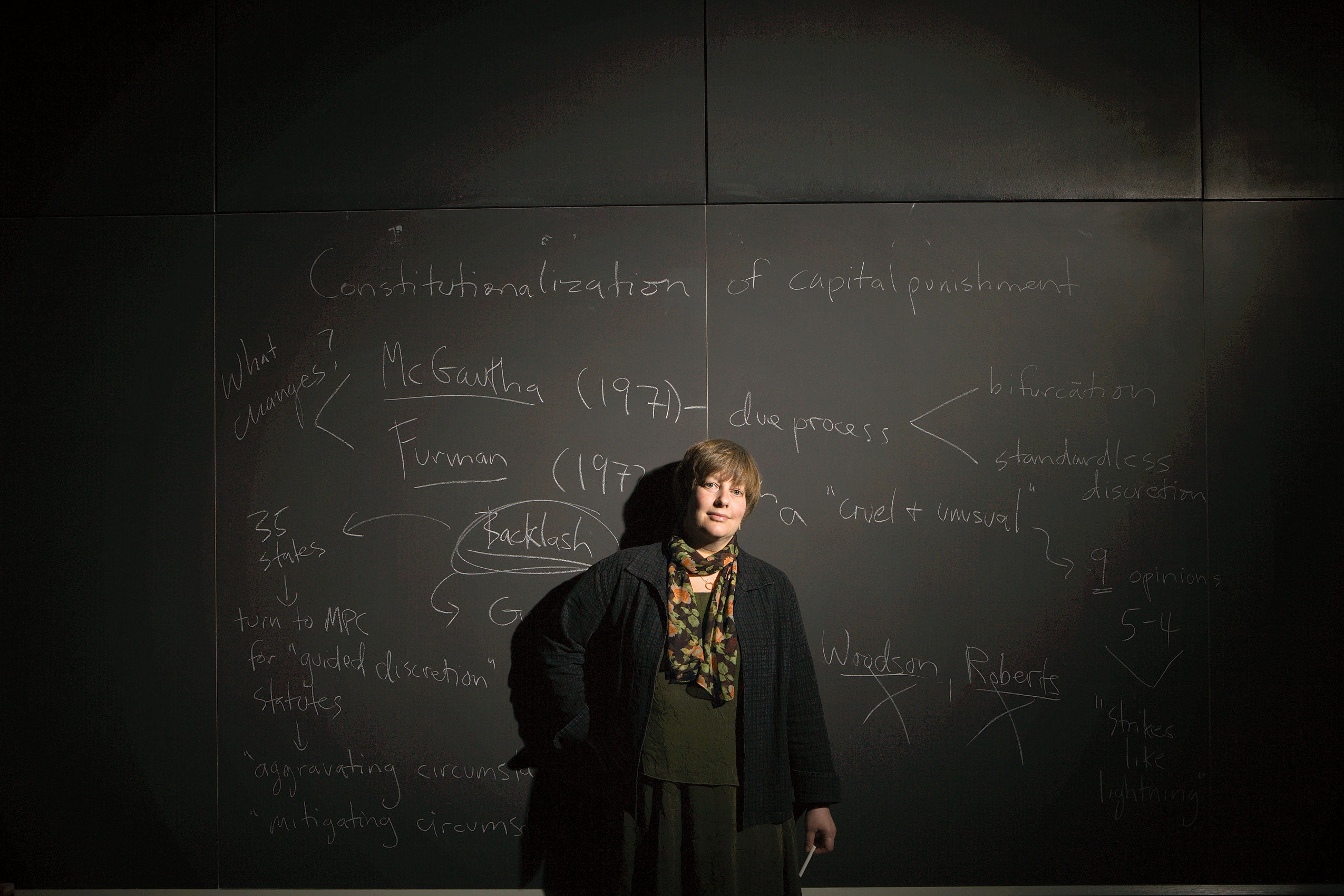

“Stay in role!” exhorts Professor Carol Steiker ’86, as some 90 students in her upper-level course Capital Punishment in America split into groups for an exercise in which they’ll argue whether a death sentence should be reversed due to ineffective assistance of counsel. “Don’t say, ‘If I were the lawyer, I would … ’”

The students step into their roles eagerly. Those playing the petitioner’s counsel argue that their client’s constitutional rights were violated when trial counsel failed to present certain mitigating evidence. One student zeros in on the lawyer’s decision to ignore a file that held information about the petitioner’s abuse in childhood, mental capacity and alcoholism.

“It was an unreasonable decision not to look at the court file,” the student asserts. But a classmate sitting as an associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court interjects: “Isn’t it possible to argue that it was a strategic decision not to look in the file?” In such cases, the Court has been less willing to interfere.

The defense group cites other missteps by the trial lawyer, including her failure to provide a narrative of the petitioner’s life circumstances. Steiker steps in as a sort of chief justice and asks, “Is it your claim that the failure to get a social history alone is ineffective assistance of counsel? Because I’m a little worried that we’re setting rigid rules. I’m hearing a checklist.”

After other students make the government’s case, Steiker asks the judges to vote: Twenty-one side with the petitioner, three with the prosecution.

The exercise is based on Rompilla v. Beard, decided in June 2005 by the U.S. Supreme Court, 5-4, in favor of the petitioner. The case was one of the last that Sandra Day O’Connor heard before she retired; she sided with the majority, overturning a 3rd Circuit decision written by Samuel A. Alito Jr.—who took her seat on the high court.

“Alito was asked a lot during his hearings about this case because he was reversed by the current Supreme Court,” says Steiker. “What will happen in the future is anyone’s guess.”

Role-playing, mock trials, guest speakers (including Steiker’s brother, Jordan Steiker ’88, a capital punishment expert) and Steiker’s teaching keep the class engaged. She began teaching the course in 1993, as a seminar. But enormous student interest prompted her to offer it as a large lecture class this year.

“It’s amazing how much this class feels like a seminar, given how big it is,” says Erica Knievel ’06. “It’s a lot of group arguments and role-playing, which sets a tone for a class where people feel comfortable participating.”

Steiker, who got a “mini crash course” in death-penalty law when she clerked for U.S. Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall, has a theory on why the class is so popular. “It’s a sexy topic, the kind of topic people think law school is going to be about,” she says. “It’s at the intersection of politics, morality, law and philosophy.”

Even though many of her students will go on to work for large firms, these firms often provide legal services in capital cases. And several dozen former students have become prosecutors and defense attorneys. Steiker says they contact her regularly for guidance: “This course actually turns out to be pretty practical.”