Despite a U.S. Supreme Court ruling that designs for cheerleading uniforms can be copyrighted, the fashion industry has not flooded the U.S. Copyright Office with claims for protection, according to retired Supreme Court Associate Justice Stephen Breyer ’64 and William Fisher ’82, director of the Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society.

That may be due in part to the reality that the industry generally benefits from limited copyright protection, according to Fisher. High-end designers make most of their money when their offerings are scarce, available to only a select few at a premium price. But when other brands later copy those designs and produce them for mass consumption, widespread adoption of the styles leads to higher demand for the designers’ next luxury creation, and so on.

“Not only is the absence of copyright protection not problematic, it’s actively beneficial to the innovators,” Fisher said.

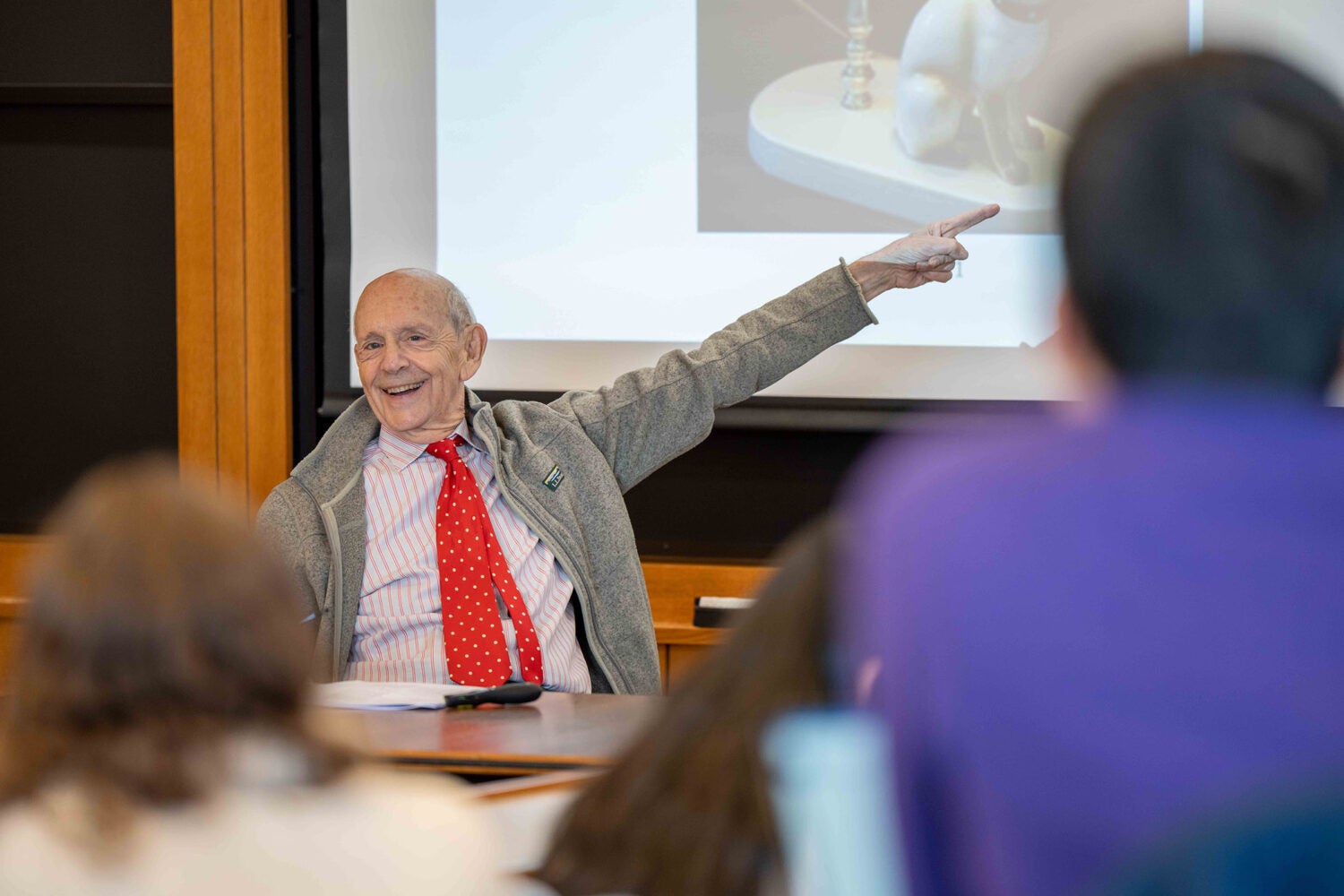

Breyer, who is now the Byrne Professor of Administrative Law and Process at Harvard Law School, and Fisher, who is also the WilmerHale Professor of Intellectual Property Law, outlined the case in question, Star Athletica, LLC v. Varsity Brands Inc., during a March 12 discussion hosted by the Harvard Fashion Law Association, the Harvard Intellectual Property Law Association, and the Harvard Journal of Sports and Entertainment Law.

During the wide-ranging conversation, Breyer reflected on the 2017 case, his dissent to the decision, the benefits and harms of copyright law, and the inner workings of the Supreme Court.

In the case, Varsity Brands, a company that designs and manufactures cheerleading uniforms, sued Star Athletica, claiming that Star’s cheerleading uniforms violated copyright protections that Varsity had on the two-dimensional designs of its uniforms, which featured chevrons, lines, curves, stripes, angles, diagonals, colors, and shapes. Star countersued, arguing that Varsity’s copyrights were based on fraudulent representations to the Copyright Office. A district court had ruled in Star’s favor, but the Sixth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals reversed, and the Supreme Court, in a 6-2 opinion authored by Associate Justice Clarence Thomas, affirmed the appellate decision.

Rejecting other tests that had been developed by lower courts, the Supreme Court held that the Copyright Act of 1976 sets forth the proper test for whether a feature integrated into the design of a “useful article” is copyrightable. Copyright protection is available if it meets two criteria, Thomas wrote: It can be perceived as two- or three-dimensional art separate from the useful article, and it would qualify for protection on its own or on another medium if it were “imagined separately from the useful article.”

In his dissent, which was joined by now retired Associate Justice Anthony M. Kennedy ’61, Breyer referenced artists Vincent Van Gogh and Marcel Duchamp, along with a cat-shaped lamp from an antique shop. Although Breyer agreed with the majority’s test, he wrote that applying it to Varsity’s designs should not result in copyright protection.

Using the example of the cat-shaped lamp, Breyer told the Harvard audience that if the cat is removed “you don’t have a lamp left… so it’s really not separate.”

Applying the test to Varsity’s cheerleading uniforms, he wrote in his dissent, demonstrates that the designs are likewise not separate from the uniforms on which they were printed.

“Were I to accept the majority’s invitation to ‘imaginatively remov[e]’ the chevrons and stripes as they are arranged on the neckline, waistline, sleeves, and skirt of each uniform, and apply them on a ‘painter’s canvas’ … that painting would be of a cheerleader’s dress,” he wrote. “The aesthetic elements on which Varsity seeks protection exist only as part of the uniform design — there is nothing to separate out but for dress-shaped lines that replicate the cut and style of the uniforms. Hence, each design is not physically separate, nor is it conceptually separate, from the useful article it depicts, namely, a cheerleader’s dress. They cannot be copyrighted.”

Fisher pointed out that Breyer’s dissent did not — as dissents often do — warn of the potential negative ramifications of the majority’s decision.

Breyer agreed, explaining that he was not overly concerned about the case’s impact on the fashion industry, where he believes design patents, trademarks, or textile design copyrights are more suitable forms of protection.

“I’m not that upset about the result in this case, but I don’t want it to apply beyond what I want it to apply to,” he said. “The threat of this case is not necessarily fashion. It’s industrial design.”

He mentioned architect Frank Lloyd Wright, as he did in his dissent, in which he wrote, “indeed, great industrial design may well include design that is inseparable from the useful article — where, as Frank Lloyd Wright put it, ‘form and function are one.’ Where they are one, the designer may be able to obtain 15 years of protection through a design patent. But, if they are one, Congress did not intend a century or more of copyright protection.”

After the discussion, Breyer took questions from the standing-room-only audience of students, including about the inner workings of the Supreme Court.

In response to an inquiry about how to persuade colleagues, Breyer emphasized the importance of listening.

“If you want to be effective at all — Nino [the late Associate Justice Antonin Scalia] thought you never could be effective; I said, ‘Yeah, sometimes you can’ — you listen,” he said. “As soon as it turns into ‘Well, I have a better argument than you’ … that will get you nowhere. If you listen to what they’re saying, maybe, taking that into account, you can come up with a compromise … and when that happens, it works well.”

The Harvard Fashion Law Association was founded earlier this year by Renée Ramona Robinson LL.M. ’25. Robinson also serves as president of Harvard Art Law Organization and launched the law school’s first-ever Art Week Symposium. For the March 12 Star Athletica event, Robinson worked closely with Trina Sultan ’25, leader of the Intellectual Property Law Association and Journal of Sports and Entertainment Law, which co-sponsored the event.

During January term, the Law School also maintains the Fashion Law Lab, an experiential course taught by Nana Sarian, a former general counsel for Stella McCartney, and Rebecca Harris ’17, an associate in Gunderson Dettmer’s strategic transactions and licensing group.

Want to stay up to date with Harvard Law Today? Sign up for our weekly newsletter.