As a fresh crop of 1Ls struggles to master the art of learning the law from reading, briefing and discussing hundreds of cases, they may be told that they have Christopher Columbus Langdell, former Harvard Law dean, namesake of its library and inventor of the case method of legal teaching, to blame. But according to Professor Charles Donahue, Langdell’s best-known innovation in legal academia may have had an earlier precursor—dating all the way back to the 13th century.

Donahue’s theory stems from his recent discovery, along with Professor Paul Brand of Oxford, of what they believe is the oldest example of a case report, dating back to 1268. Although scholars of English legal history had long believed that case reports—or short summaries of what transpired in English courthouses—did not begin to be recorded until later in the 13th century, Donahue and Brand separately discovered two different reports of a case from the middle of the 13th century concerning a land dispute over 45 acres and a mill in a small village in the south of England. The case centers on whether one of the parties in the case could be barred from making a claim that would be contradicted by something he said in an earlier case—an issue now known as collateral estoppel.

***

One Text, Sixteen Manuscripts: Magna Carta

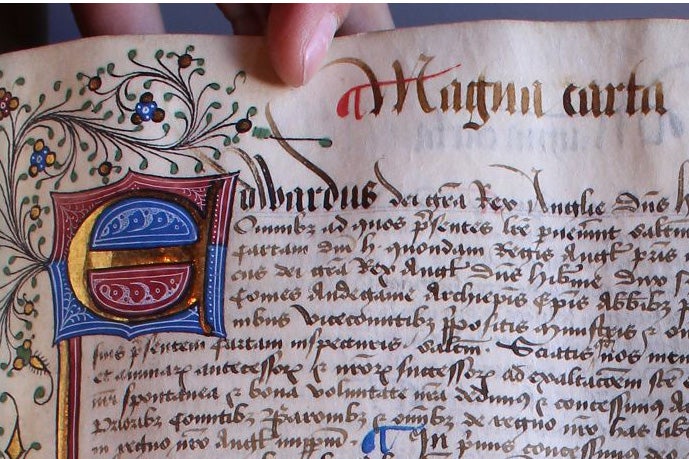

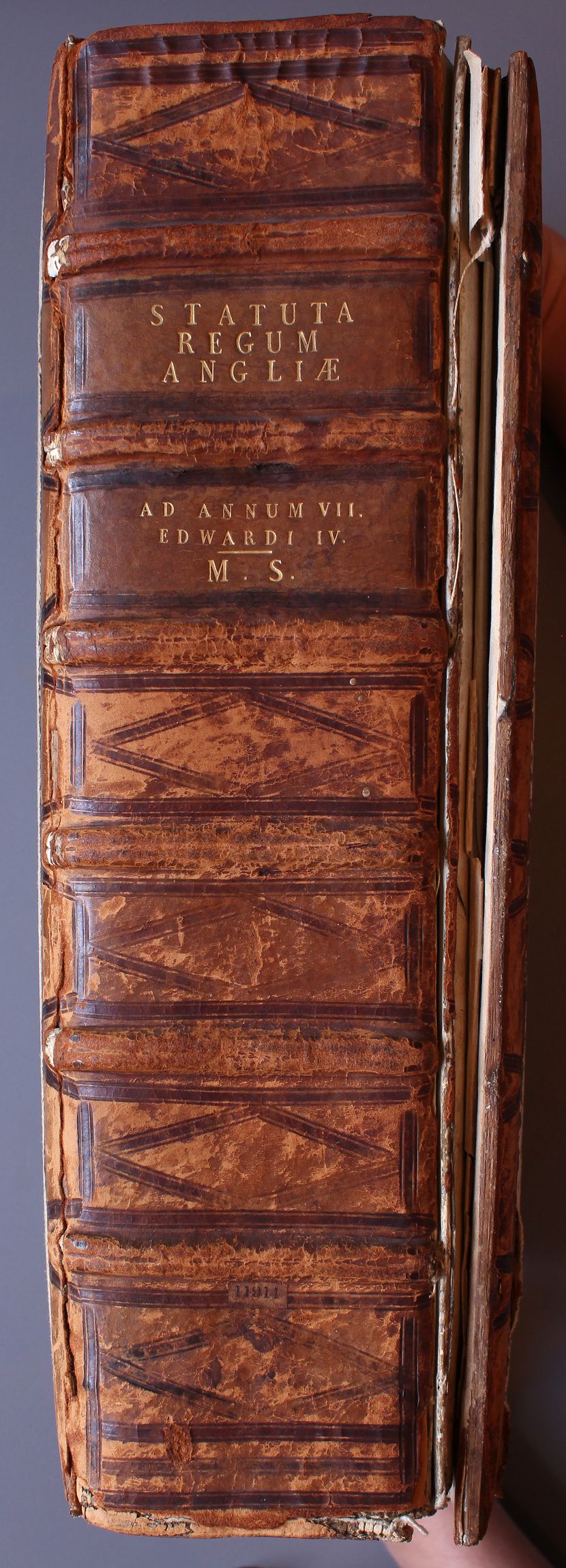

To celebrate the 800th anniversary of one of most famous of legal documents in history – the Magna Carta – the Harvard Law School Library’s Historical & Special Collections has mounted an exhibit of several manuscript versions of the well-known charter, titled “One Text, Sixteen Manuscripts: Magna Carta.” The Library recently digitized its entire manuscript collection of English statutory compilations, which include Magna Carta, dating from about 1300 to 1500.

The exhibit is on view daily from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. in the Caspersen Room through March 11, 2016.

***

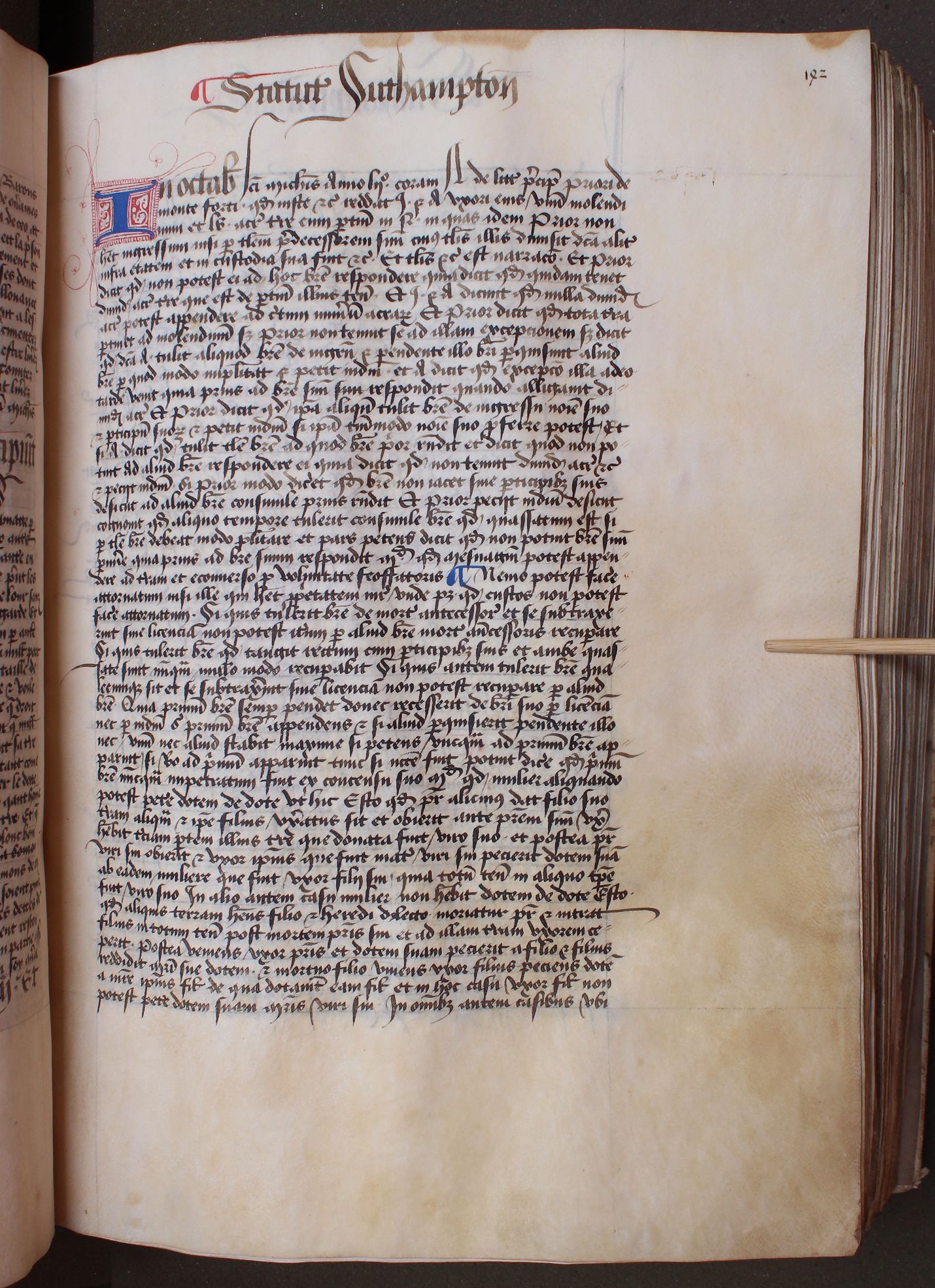

Donahue discovered the case report through a project involving the digital cataloging of Harvard’s collection of medieval manuscripts, assisted by the Ames Foundation, which funds research in legal history. The report, written in Latin, came to light only through the lucky mistake of a scribe, who labeled the case the “Southampton Statute” and included it in a statute book compiled in the 1460s. But Donahue says that the case is clearly a report, not a statute, and that it was probably mistakenly included due to a list of legal rules that appear in conjunction with the report, which Donahue and Brand suspect were actually teaching notes. “Somebody used this case as a vehicle for instructing people in law,” Donahue said. “And if that’s right, then not only is this the earliest example of a reported case, but it’s the earliest example of a teacher of Anglo-American common law using the case method.”

When Donahue found the Southampton Statute, he sent it to Brand, a legal historian, and asked if he recognized it. Brand replied that not only did he recognize it, but it was the same case—though a longer version—that he had published as the very first manuscript in a compilation of the earliest English law reports. Brand had discovered a separate manuscript at the Huntington Library in California, recorded by a different scribe and also mistakenly included in a book of statutes. “This is just something somebody in the 15th century got wrong, and because they got it wrong, these two examples survived,” Donahue said.

According to Donahue, although the use of legal precedent and doctrine in the late 13th century was not quite as sophisticated as it is today, early examples of case reports make clear that lawyers more than 700 years ago structured legal arguments by using legal rules adopted in earlier cases and applying them to new and unique fact situations. “The process by which case reporting came to be a dominant feature of English law ends up being pretty important, because the common law is much more case-based than the law in the Continent,” Donahue said. “It is interesting to see how it actually started, and how closely it is connected with instruction.”