As part of a series examining the first year of the Biden presidency, Harvard Law Today asked Premal Dharia, lecturer on law and executive director of Harvard Law School’s Institute to End Mass Incarceration, to share her thoughts on the administration’s successes, failures, and agenda for the future.

Harvard Law Today: What has the administration done right so far?

Premal Dharia: I appreciate that this starts with a positive question; it’s a helpful reminder that it’s important to appreciate all steps forward, even if there are not nearly enough of them. The one move the Biden administration has made thus far that is positive is a dedicated push to fill vacancies on the federal bench with people that are incredibly equipped to be in that role. The administration has made a concerted effort to put public defenders and civil rights lawyers in judicial roles – and to move to fill vacant judicial roles with urgency. The role of judges has often been overshadowed by that of litigators in the system – prosecutors, for example – but judges carry tremendous potential to intervene in the cycle of mass incarceration. Having people on the bench who understand that cycle, who have worked in or around it and know its intervention points and the trauma it inflicts on real people, will be an essential part of working to end it. It has been heartening to see the president move quickly and deliberately on this front.

HLT: What has it gotten wrong?

Dharia: Well, a lot. For some initial context, the federal prison population has increased by about 5,000 people since Biden took office. This isn’t entirely the fault of the administration – we are also grappling with a time of systemic upheaval due to the pandemic – but it is important to note, especially since Biden campaigned on a promise to reduce the prison population.

The biggest thing I believe our Democratic leadership has gotten wrong is not engaging with where the American people are right now.

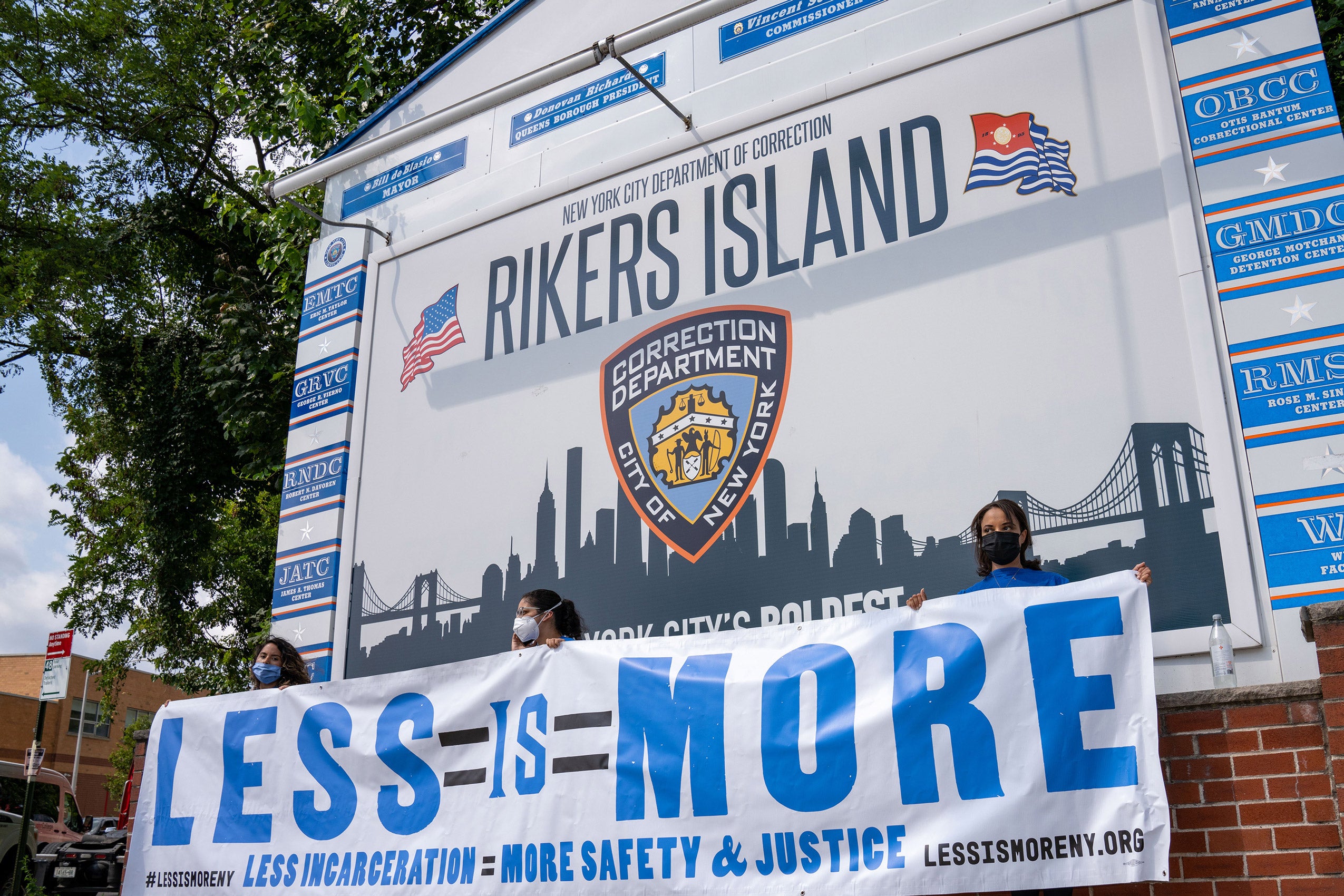

Perhaps the best answer I can give here is that the biggest thing I believe our Democratic leadership has gotten wrong is not engaging with where the American people are right now. And not engaging with this particular moment, in which our country had an unprecedented popular uprising in response to policing and in which popular opposition to the criminal legal system is robust. The failure to engage with that, to really listen to that, has signaled that this administration simply will not lead on criminal system reform despite its promises. And indeed, the administration has been timid about moving forward even the reforms that it promised, including on clemency, sentencing reform, or the improvement of conditions for those incarcerated. It took months of deliberation and advocacy just for the administration to recently determine that thousands of people released under the CARES Act did not have to be re-incarcerated. This pace and these failures to act do not spark hope.

HLT: What has the administration not addressed yet that it should?

Dharia: While most criminal “justice” is administered at the local and state level, the executive holds real power to change infrastructure, to change practices at the federal level, and also to set a model for local leaders. President Biden has not done nearly as much as he could have by now, even in the face of pandemic-related crises. For example, he has yet to issue a single grant of clemency, much less move forward on excellent reform proposals offered by clemency experts, such as creating an independent clemency board. He has not yet filled the many (6 out of 7 seats!) vacancies on the sentencing commission. He continues to turn to the Department of Justice, a prosecuting body, as the center of potential change, when experts have warned that that is a doomed path (and, indeed, we continue to see federal prosecutors around the country opposing compassionate release and sentence reduction requests and federalizing gun possession charges). And, as Omicron rages through federal jails and prisons, where we have deprived people of the autonomy to protect themselves, the administration has only just now – in January 2022 – moved to replace the director of the Bureau of Prisons, a shift that lawmakers and advocates alike have long called for. These are all missed or delayed opportunities to make real change at a time when our country needs it the most.

HLT: What are the biggest challenges the administration faces to its agenda going forward?

One thing that has been demonstrated over and over again, through these last decades of the painful American experiment with punishment, is that what we have done thus far not only does not work – it makes us less safe.

Dharia: The biggest obstacle it faces is itself. There are clear paths forward on some of the most basic reforms. There are excellent advocates that have offered expert guidance on how these reforms can be implemented. And there a host of ways in which independent bodies, commissions, and agencies could undertake the work of reform in a way that the administration has not and likely will not – if only they were populated and given the green light to do so. And while these reforms will not end the harms of the criminal legal system, they could go a long way toward shifting structure and practice away from the punitive approach that we know is counter-productive toward an approach more grounded in health, safety, and freedom. And they would at least begin to signal to communities across the country that they are being heard. There are a lot of false and misleading narratives out there today about crime and reform. One thing that has been demonstrated over and over again, through these last decades of the painful American experiment with punishment, is that what we have done thus far not only does not work – it makes us less safe. If its campaign promises meant anything, this administration needs to get out of its own way, abandon its timidity and backtracking, understand the urgency of the moment, take action where it can, and create pathways for others to take action where it cannot or will not.

Read the series Weighing President Biden’s first year