Who is allowed to vote — and how?

Even in politically polarized times, nearly everyone can agree on the sanctity of elections and the importance of civic participation, yet those two simple questions have many possible responses, each with profound implications for the United States. And as renewed debate over voting rights, election security, and redistricting has begun to play out in state legislatures, on Capitol Hill, and in the courts, how we answer them will be critical to the future of American democracy.

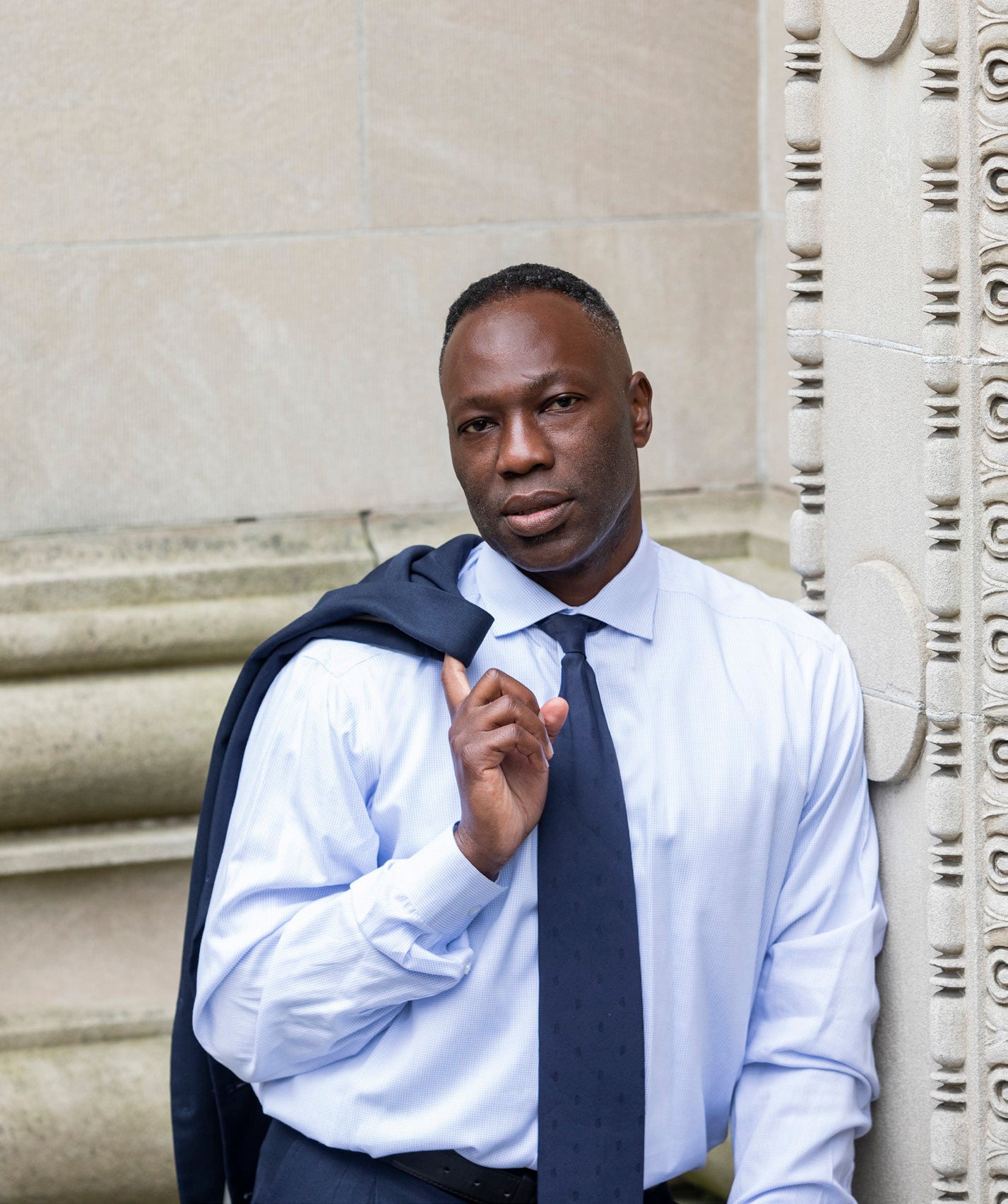

“Our politics are affected by our constitutional structure, our legal structure,” says Guy-Uriel Charles, the Charles Ogletree, Jr. Professor of Law at Harvard Law School. “For people to get what they want — for people to engage in self-governance — they have to understand and address those rules and the questions and problems that constrain their ability to govern themselves.”

These rules formed the basis of Charles’ Election Law course this past spring. The class examined the U.S. election system, including the structure and theory of the democratic republic, the history of suffrage and voting rights, the party system, and campaign finance concerns.

“How could you hold your politicians accountable if they are making it harder for you to vote? How could you hold them accountable if you can’t contribute monetary resources and funding for campaigns? How could you hold them accountable if your district is gerrymandered? Those are the types of questions that election law addresses, and they’re core to any modern democracy,” he says.

While Charles co-wrote the course’s casebook, his goal was to move beyond pure doctrine. “We are trying to paint a picture of what type of democracy we want and law’s role in facilitating that democracy, instead of simply describing the type of legal system that we have,” he says. “We’re asking really difficult questions, and we’re thinking much more normatively about the way things ought to be, and how to make them happen.”

This mix of doctrine and debate appealed to Zachary Goldstein ’23. “Professor Charles is super engaging, because he’s good at balancing the black letter law with why it all matters,” he says.

Take the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which outlawed racially discriminatory voting practices. Two notable cases decided in the last decade, Shelby County v. Holder (2013) and Brnovich v. Democratic National Committee (2021), have narrowed the voting law’s scope. In class, discussion of those cases “resulted in a broader conversation about where we go from here, including what tools voting rights advocates should be focusing on if they are hoping to accomplish the same goals with a more limited toolkit,” Goldstein says.

Courtney Brunson ’22, who will work for a firm that focuses on political and voting law after graduation, enrolled in the course to develop a foundational understanding of the issues. “As someone who cares about the current state of American democracy, I wanted to more broadly explore the curiosity I had about what actual laws, procedures, and rules we had around how we navigate the rights of citizens, candidates, and other groups who participate in the elections process,” she says.

Debating a better democracy

Of course, reasonable minds can — and do — disagree about how to best structure our electoral system, and Charles says respectful discussion was a crucial component of each class. “We’ve had some really amazing discussions this semester,” he says. “I tend to express a strong view, partly because I want clarity on the question, but also to provide something for the students to react against. And my favorite discussions are the ones in which students respond in ways that challenge and refine my own thinking on things.”

For many students, the course was also a valuable opportunity to discuss voting rights and election law issues in real time. “There is a current case out of Alabama that might completely change how the Supreme Court interprets racial gerrymandering and the Voting Rights Act, and we were able to discuss that during class,” says David Scharf ’23. “It was really fascinating to be in this course while that was happening.”

“We are trying to paint a picture of what type of democracy we want and law’s role in facilitating that democracy.”

With a firm grounding in the history of election law, students are better prepared to tackle the pressing problems of today, says Charles. “What do we do about the Voting Rights Act, now that the Supreme Court has struck down some of its important provisions? We also have a campaign finance system that is dysfunctional. And how should we think about gerrymandering? Big questions are now on the table, and we are in many ways rethinking the fundamental architecture of American democracy.”

It’s a rethinking with implications for all Americans. “Electoral outcomes are not merely a reflection of the electorate’s preferences,” says Brunson. “They are a reflection of how the systems are created, the forms of preferences are aggregated, and the rules of these processes are implemented.”

A functional democracy, says Scharf, depends on the ability of people to participate in the political process.“Generations of people have fought for the right to vote, whether it was the formerly enslaved, women, poor Americans, minority Americans. It’s so important that people show up to the polls and express their voice, and make sure that legislators are listening to them.”

And Charles’ course made it clear that the stakes are high. “In the U.S. and globally, we are in this moment of democratic backsliding,” says Goldstein. “The issues of election law, voting rights, democratic reform, and democracy more broadly are especially important now. It feels like an important moment to think about how we stop the backsliding, but also how we move forward to rebuild trust in democratic institutions.”