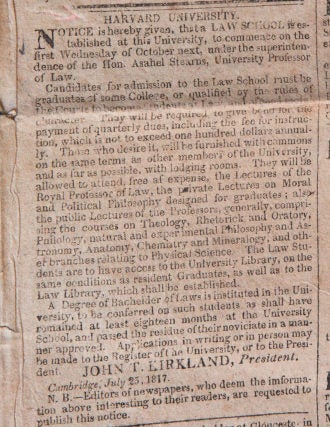

“Notice is hereby given that a law school is established at the University to commence on the first Wednesday in October next,” began the Aug. 9, 1817, advertisement in Boston’s Columbian Centinel, one of many newspapers and journals that touted the opening of a new law school, in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

It promised a program unlike any that had been offered in the nation before—bringing intellectual rigor to the study of law, “under the patronage of the University,” while still preparing graduates for practice in the profession.

Candidates for admission, announcements read, “must be graduates of some college,” or qualified after “five years study in the office of some Counsellor.” Those students who remained at least 18 months at the “University Law School” or “passed the residue of their noviciate” would be granted the new Bachelor of Laws degree.

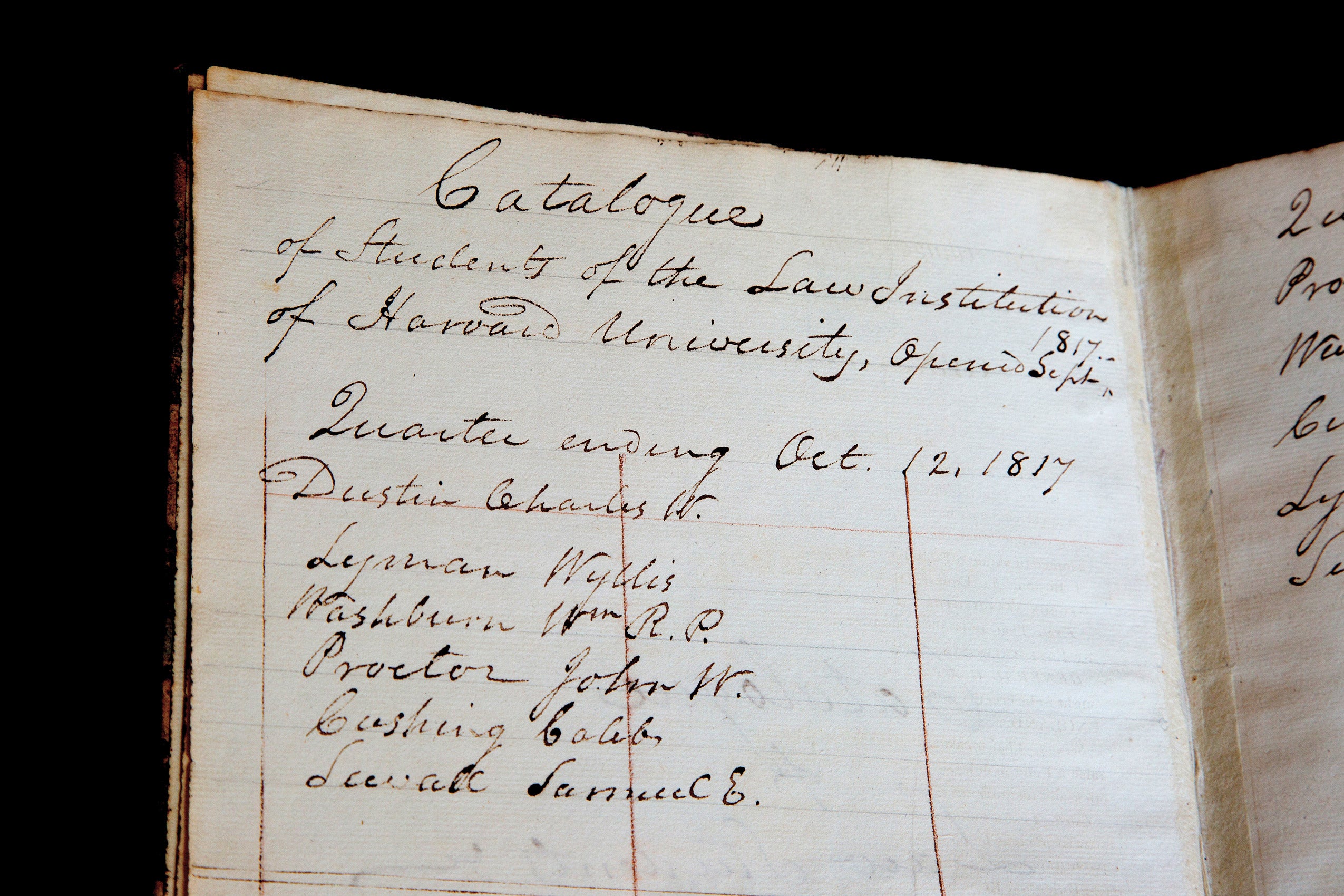

By October, Charles Moody Dustin, a 20-year-old from Gardiner, Maine, was the first to enroll in the school. He was joined by five other young men over the course of the year.

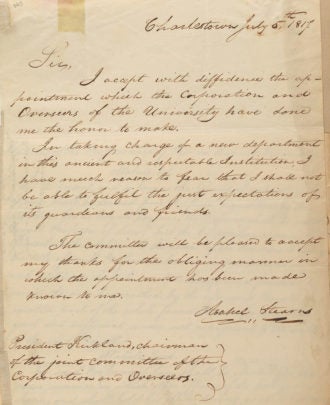

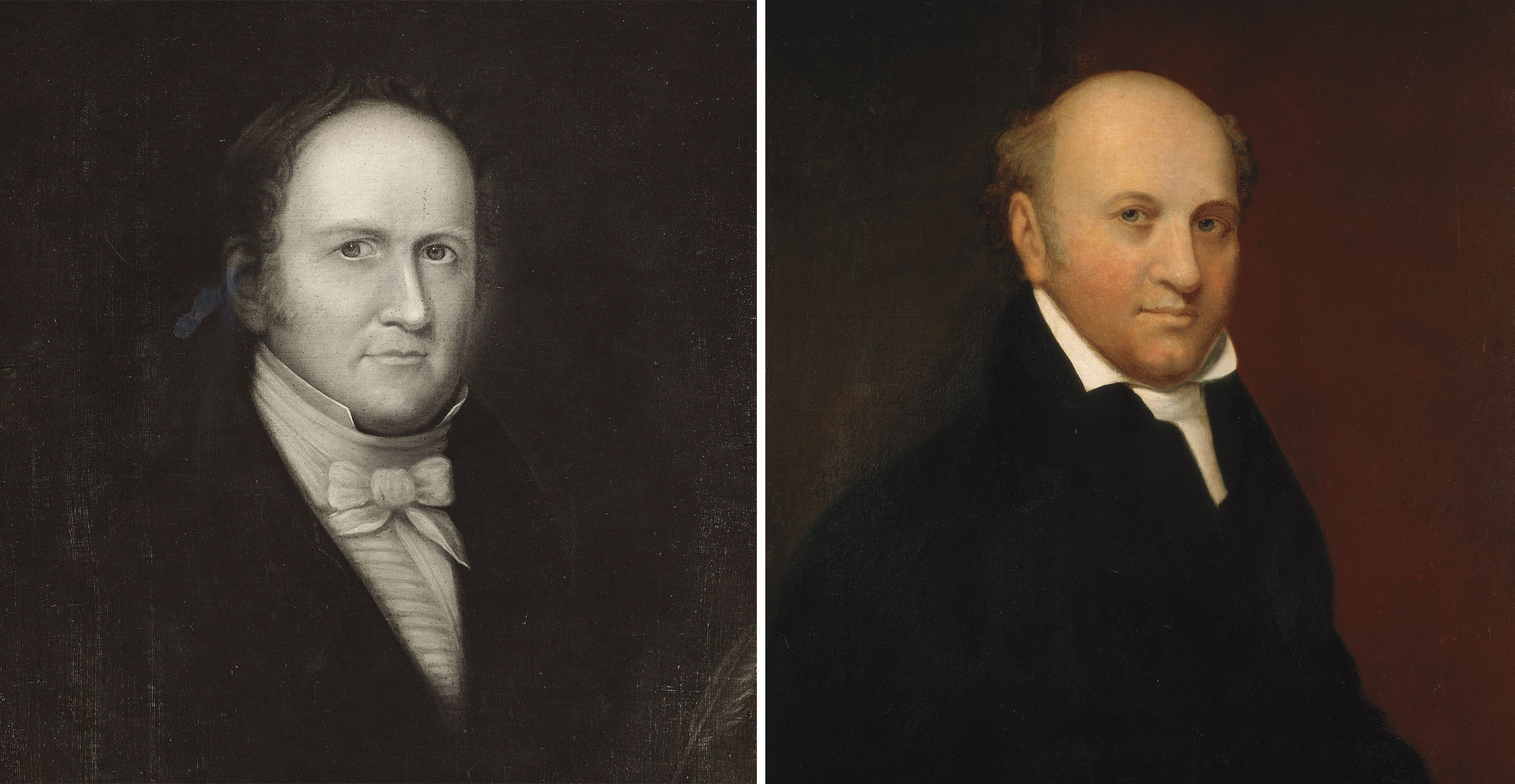

Asahel Stearns, the first University Professor of Law, did most of the teaching and shouldered the day-to-day duties of running the school—everything from obtaining books for the library with the meager funds allotted him, to taking care of students who fell ill. He was an experienced practitioner who served as the district attorney of Middlesex County, credentials that enabled him to assess a young future lawyer’s readiness to practice. In addition to attending lectures, students took part in moot courts and debates and completed written assignments.

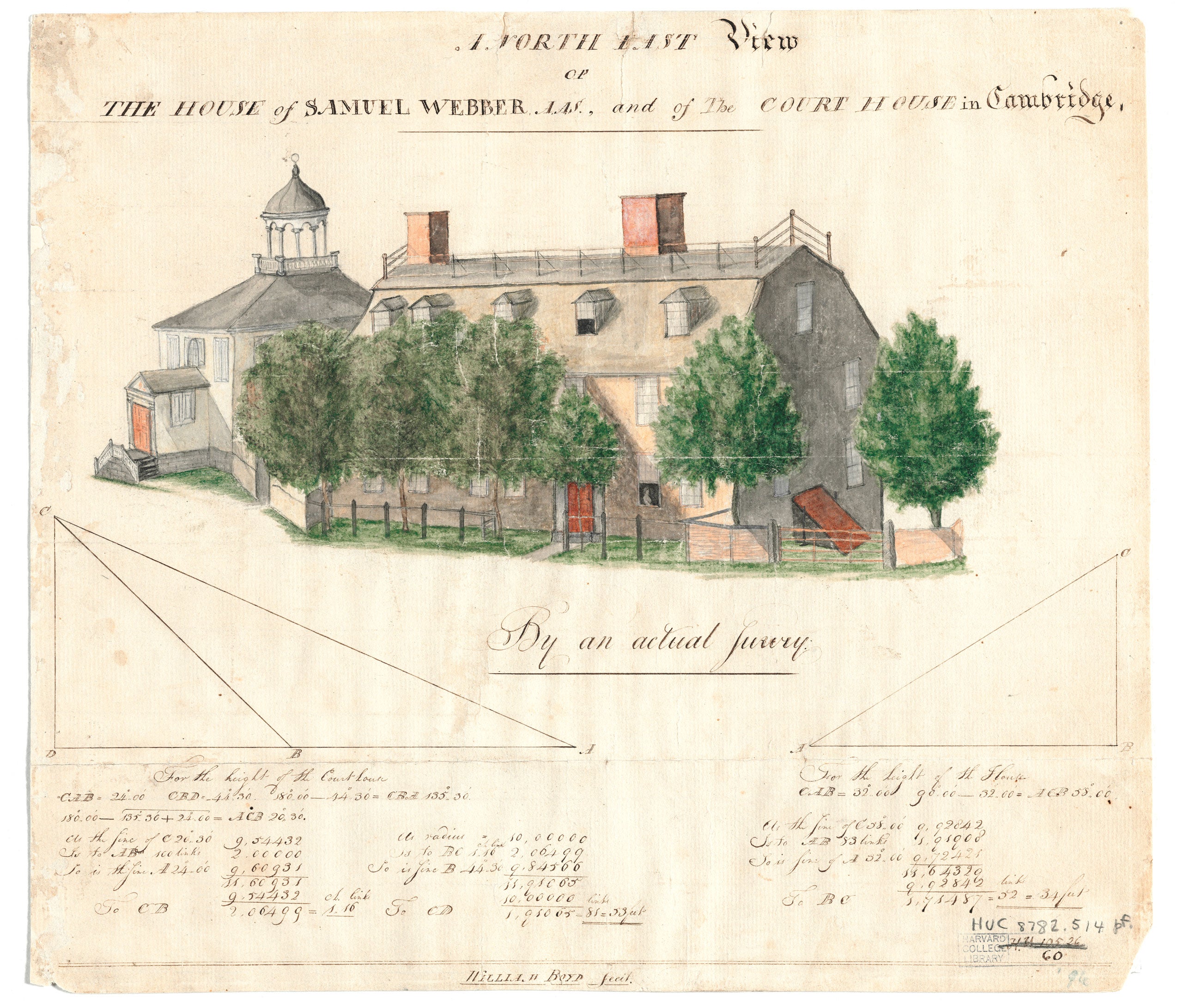

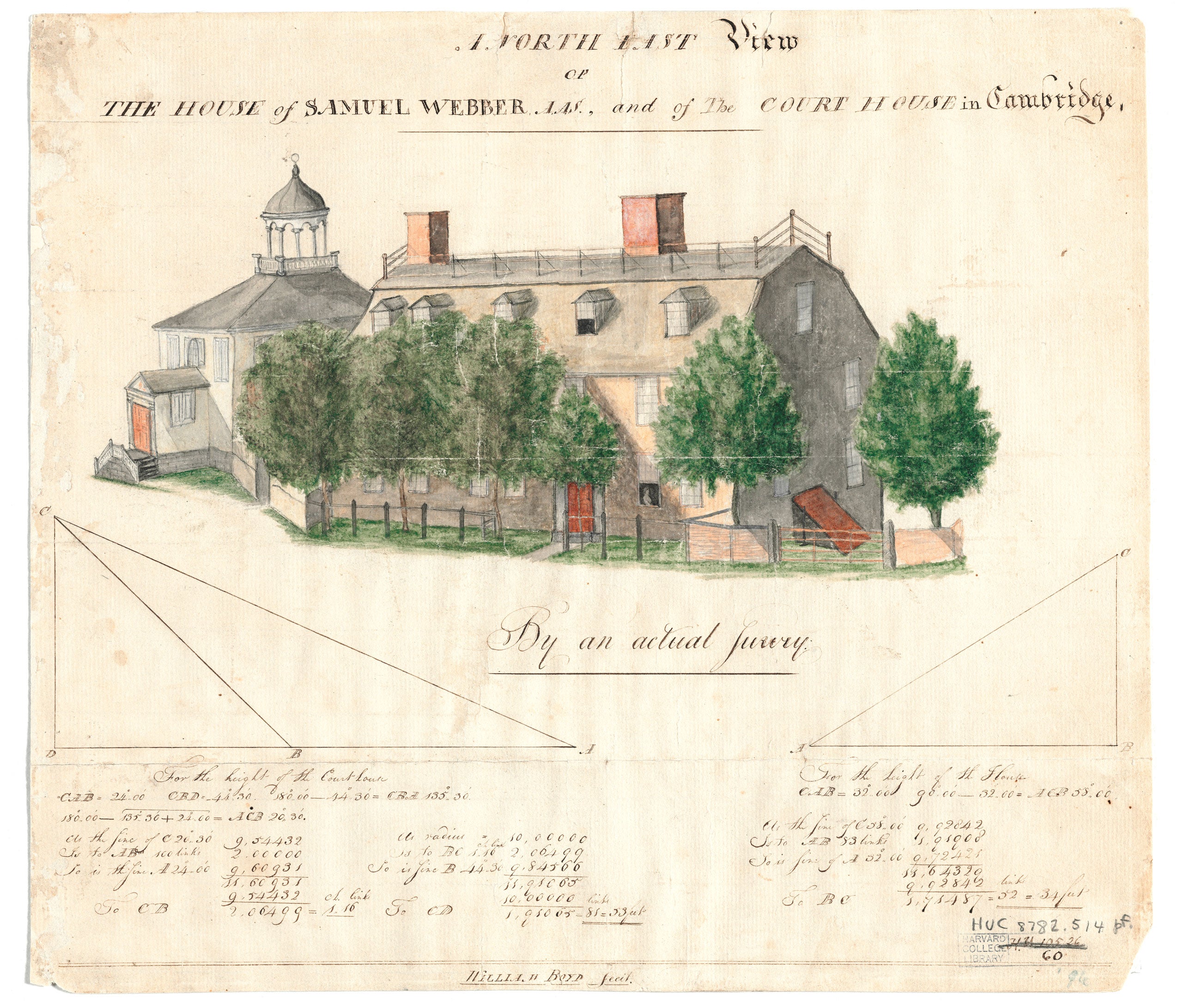

The six students attended classes on the first floor of College House Number 2, a two-story brick building in Harvard Square. Space was tight. One room served as a lecture hall, student meeting space and library. Stearns’ faculty office doubled as his law office. (Because his salary consisted of the tuition paid by the students, maintaining a private practice was a financial necessity.) There was also a closet-sized space designated for a librarian (but no money to hire one). Although not ideal, the building had at least one advantage—it was close to the Middlesex County Courthouse, which gave students easy access to observing court proceedings.

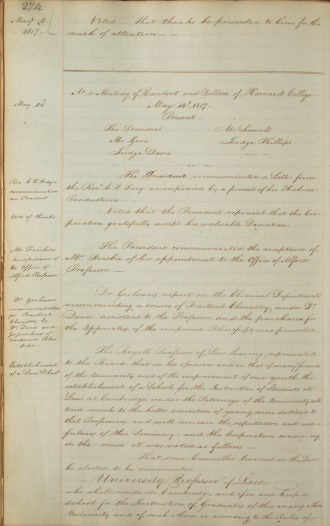

Students also attended a series of lectures offered by Massachusetts’ Chief Justice Isaac Parker, the senior member of the law faculty, on topics ranging from U.S. constitutional law to natural law. Parker was the first holder of the Royall Professorship of Law, endowed in 1815 through the bequest of the family of Isaac Royall, a wealthy Antiguan plantation owner and slaveholder. Initially, Parker was charged with offering lectures in law to Harvard undergraduates, an experience that confirmed for him the merit of creating a professional law school at the university.

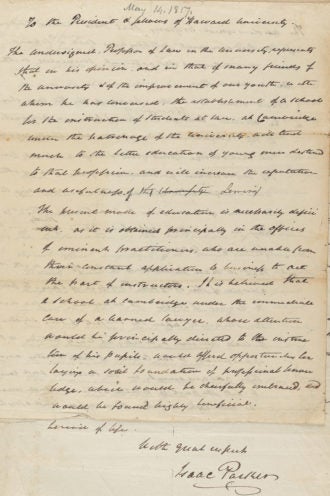

On May 14, 1817, Parker outlined his plan for a law school in a letter to the Harvard Corporation and proposed that they vote on establishing a professional school at the university “under the immediate care of a learned lawyer, whose attention would be principally directed to the instruction of his pupils [which] would afford opportunities for laying a foundation of professional knowledge.” The plan was approved on June 12, 1817, which could be considered the birthday of Harvard Law School.

From the Archives: Documenting Harvard Law School’s Founding