In September of 1845, Harvard Law School was shaken by the death of Professor Joseph Story (1779-1845). His passing left Simon Greenleaf (1783-1853) the sole teacher at HLS. In the dozen years since Greenleaf’s arrival in 1833, he and Story had been equal partners.

Greenleaf, after all, had joined the legendary Story to prop up the ailing law school and bring it back to sturdy life. In 1829, the year Story arrived, HLS—shakily about to enter its third decade—had six students. The coursework was lax, the library scanty; competition was still fierce from traditional apprenticeships and from rising proprietary schools like the one in Litchfield, Connecticut; and Harvard itself was rocked by a financial crisis. By the fall of 1833—with the law school propped up by a benefactor (Nathan Dane) and a new Harvard president (Josiah Quincy)—Greenleaf arrived at an HLS that had enrolled a record 56 students.

“We have shared the toils together,” Story wrote to Greenleaf in 1842, and “you are in every way entitled to an equal share (of respect) with myself.”

Gospel Truth

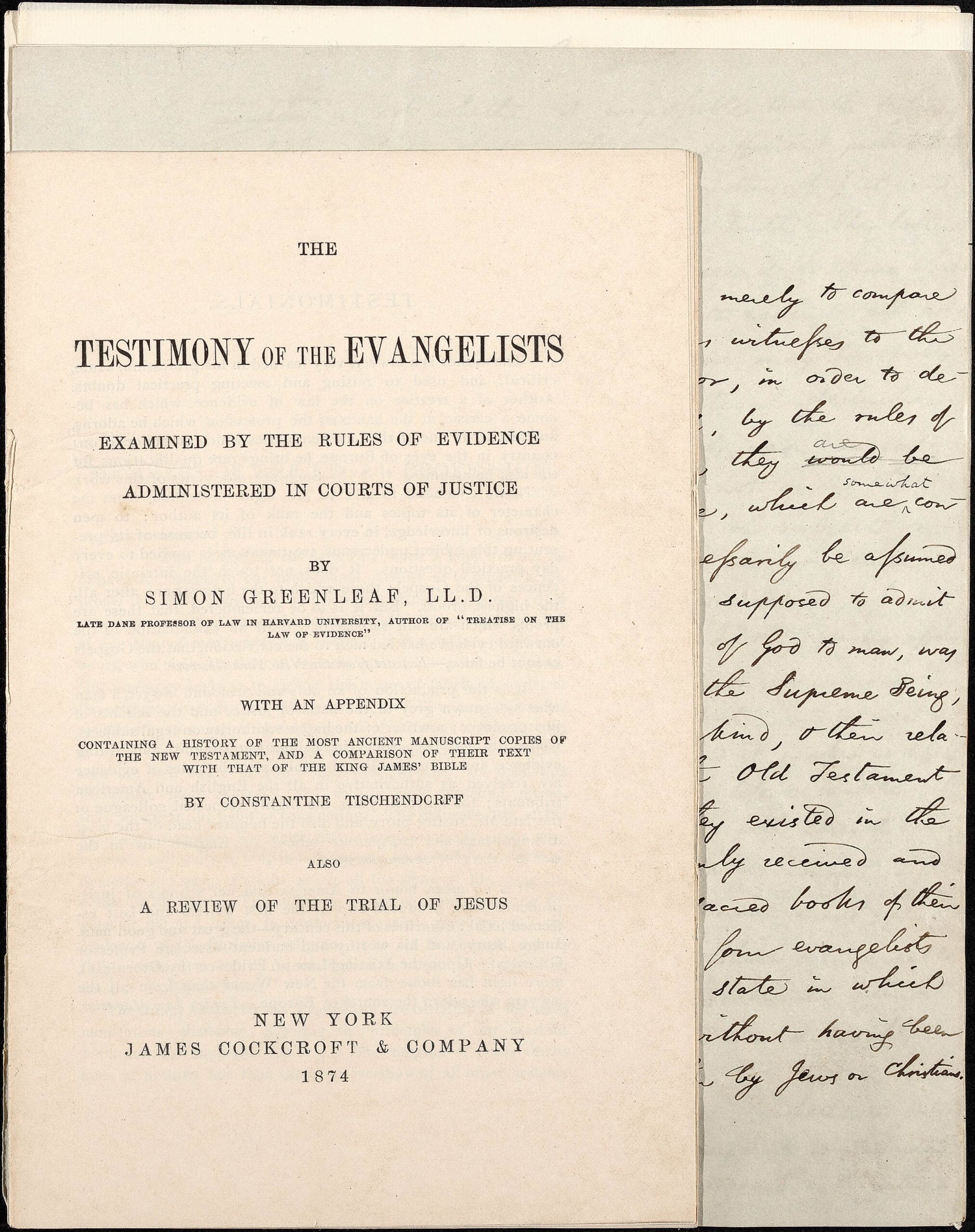

In 1842, Simon Greenleaf published the first volume of his masterwork, “Treatise on the Law of Evidence.” He would go on to write a book that used the rules of evidence, cross-examination, and other legal tools to investigate the Gospel accounts of Jesus, the crucifixion and the resurrection. “The Testimony of the Evangelists,” as it is now known, made him prominent among 19th-century practitioners of Christian apologetics, the centuries-old use of reason to defend and explain Christianity. In fact, Greenleaf regarded law school itself as a form of Christian evangelism, wrote Alfred Konefsky in his study “Piety and Profession,” just like the Bible, temperance, colonization and peace movements that drew his lifelong sympathy. A law school graduate, according to Greenleaf, would be humane, legally adept and morally active.

The recent digitization of the Simon Greenleaf papers—26 boxes of letters, cases, legal opinions, tracts, and complexly layered manuscripts—documents a collaboration between the two men so thorough it included acquiring artwork to decorate the law school. (We learn this from an 1840 letter from Greenleaf and Story to Chief Justice Lemuel Shaw of the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court, looking to acquire a bust of Shaw to display in Dane Hall.)

The collection also provides the opportunity for virtual visitors to acquaint themselves with Greenleaf himself: an unsung “genius,” according to HLS Visiting Professor Daniel R. Coquillette ’71. (Coquillette is co-author of a new history of Harvard Law School.)

Greenleaf’s scholarship, he suggests, foreshadowed the case method approach of Christopher Columbus Langdell LL.B. 1854 and the legal realism of Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. LL.B. 1866.

Visitors to the Greenleaf papers can “open” folder 10 in box 2 and see Greenleaf’s inscription on the bound collection of 65 letters from Story. They can look for letters from abolitionist Charles Sumner LL.B. 1834, legal theorist Francis Lieber or the plain-spoken Josiah Quincy. They can see letters and documents related to the Temperance Movement, the American Colonization Society, and Liberia (Greenleaf drafted the original constitution)—interests that reflect the evangelical Christian beliefs that Greenleaf wove into his ideal of how the law should be taught: as a moral science.

The same visitors might take note of Greenleaf’s rapid, right-slanting hand and its generous spacing between words, as if to say—lawyer-like—that each has an intentional, hard-fought meaning. Greenleaf also had an appetite for energetic editing and rewriting. His bound volumes, foldouts, overlays, glued-on new paragraphs and spidery marginalia all made digitizing the papers a challenge.

Within a year, the Greenleaf collection will be online as a “suite,” searchable by words, dates, names, document types and themes. Meanwhile, visitors can navigate Greenleaf’s digital papers to assess his legal reasoning and his deep editing, and even to peruse his clothing bills (always less than he spent at the butcher). They can also find glimpses of the private, scholarly man who helped save Harvard Law School. In one letter, Charles Sumner summed up both Greenleaf and his writing style. “Neat, apt,” he wrote, “polished, lucid.”