You can’t please all the people all the time. Government officials, political reporters, and policy advocates — perhaps more than anyone — are well-aware of this fundamental truth.

But thanks to a new freeware data tool created by experts from Harvard Law School and the Bloomberg Center for Cities at Harvard University, determining the policy preferences of constituents in any geographic location within the United States just became infinitely easier.

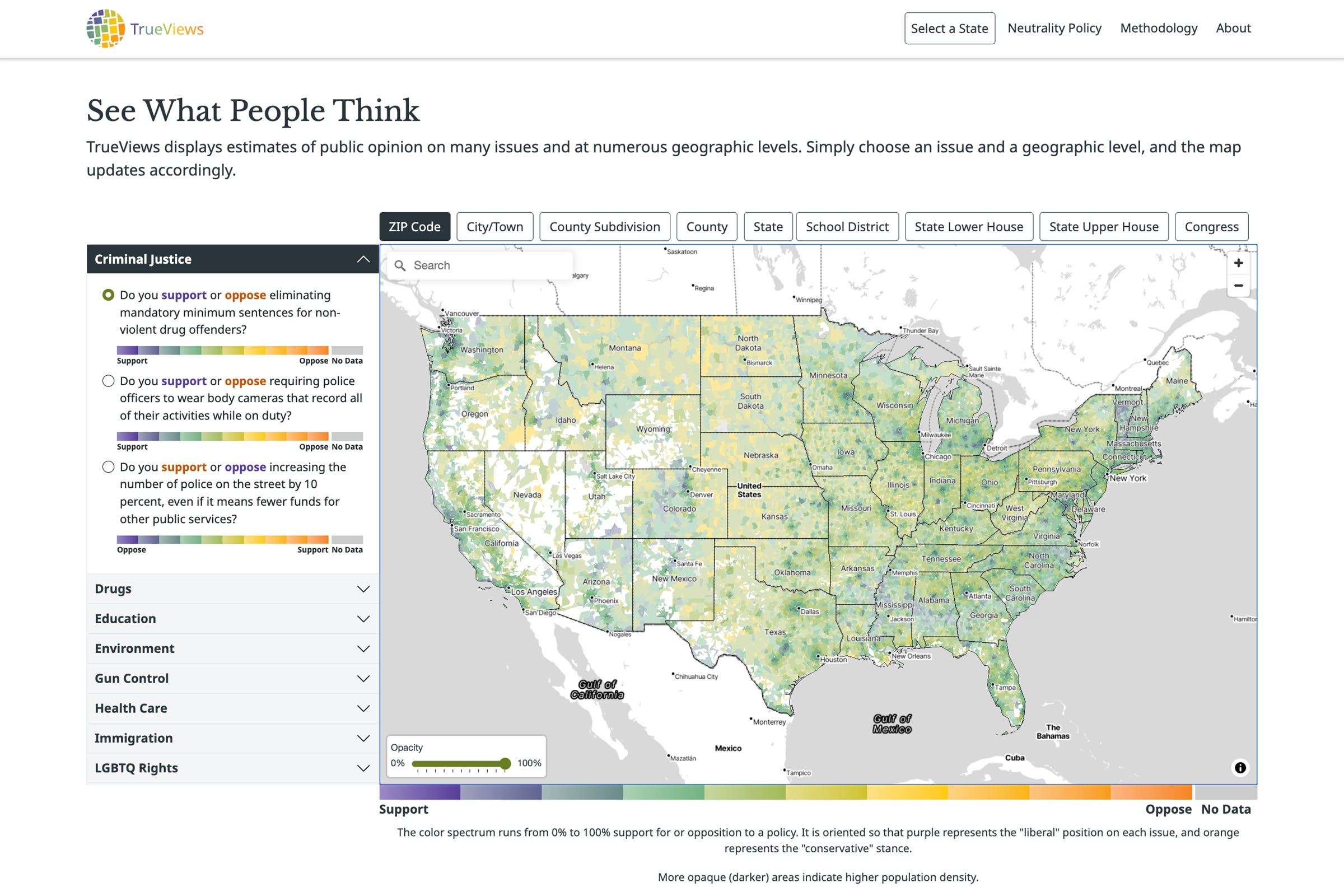

At first glance, the visionary “TrueViews” data platform looks like a standard map of the United States. But as soon as users move their cursor over any geographic location on the diagram, the tool’s true value comes to life.

Using survey results from over one million Americans, TrueViews provides users an immediate snapshot of how residents in any particular state, county, district, city/town, or zip code feel about 32 different policy issues ranging from marijuana decriminalization to universal healthcare to fossil fuel emission limits.

By simply selecting one of the issues — for example, “Do you support or oppose eliminating mandatory minimum sentences for non-violent drug offenders?” — and any jurisdiction within the United States, TrueViews immediately generates a color-coded geographic overview and estimates of what percentage of residents support or oppose the policy selected.

The goal, according to its creators? Equip decisionmakers and information providers throughout the country with a more accurate understanding of how the people they serve feel about important policy issues.

At the platform’s official launch last week, Director of the Election Law Clinic at Harvard Law Professor Ruth Greenwood moderated a panel of key experts who helped bring TrueViews to life including Harvard Kennedy School Associate Professor of Public Policy Justin de Benedictis-Kessner; Christopher Warshaw, a professor of political science at George Washington University School; and the former mayor of Topeka, Kansas, Michelle De La Isla.

Greenwood, a TrueViews co-creator, engaged her colleagues in a conversation about their contributions to the project, the value of the information it provides, and their expectations for its utilization going forward. Prior to the panel, Harvard Law Professor Nicholas Stephanopoulos introduced audience members to the platform website and shared how his inspiration for collaborating on this project arose out of a desire to help bridge the ever-growing gap between the perceptions of modern lawmakers and the actual opinions of their constituents.

“There’s a really profound mismatch between polarized politicians today and much more moderate voters — many politicians misperceive the views and preferences of their constituents,” said Stephanopoulos, the Kirkland & Ellis Professor of Law at Harvard Law School. “Elected officials often think that voters are much more ideologically extreme than voters actually are.

“The same goes for staff,” he added of the people who work for office holders. “A recent study looked at staffers’ perceptions of congressional district opinions and it tells the same story. Democratic and Republican staffers give wildly different estimates of district opinion on major federal policies, and both Democratic and Republican staffers get it hugely wrong.”

But is the source of this “mismatch” honest misperception on the part of government officials, or plain indifference to constituent opinions? According to Stephanopoulos, recent studies suggest elected officials are receptive to constituent feedback, but simply lack accurate information.

“The politicians who got this data, their eventual votes were highly responsive to public opinion in their districts. The more that their constituents supported a proposal, the more likely the politicians were to vote for the bill,” said Stephanopoulos. “On the other hand, in the control group, when they didn’t get this data about public opinion, there was no consistent relationship between what voters wanted … and what the representatives actually did.”

Local governments in particular, according to de Benedictis-Kessner, tend to have glaring data gaps that a free, user-friendly platform like TrueViews could help rectify.

“One of the things I’ve learned from working with lots of Harvard Kennedy School students over the years, and with city governments, is that often cities do not have any data on what their constituents think,” said de Benedictis-Kessner, who also serves as the faculty director of the Harvard Kennedy School Local Politics Lab. “City governments are often understaffed and under-resourced and can’t run their own polls on important public opinion issues. They’re left without any kind of data, so it might be especially important for local governments to have this as a tool.”

To provide the most accurate data projections possible on such a wide variety of issues, TrueViews’ creators compiled survey results from 14 years of Cooperative Election Studies (2009-2023) and three years of UCLA/Nationscape Surveys (2019-2021), drawing data from 18 large-scale surveys of the American public that received more than a million responses. As part of the platform’s multilevel regression and poststratification strategy, TrueViews also provides a “level of confidence” metric that quantifies the probability of accuracy for each projection.

The fact that the data often deviates from commonly held assumptions about constituent opinions in certain areas is a feature, not a bug, explained Warshaw, who helped design the program’s polling data methodology.

“What I hope about the tool is that people from both parties and of all political persuasions will find some data here that makes them really annoyed, that, like, disagrees with their prior conceptions about the world,” said Warshaw. “And maybe that will change their views a little bit, or maybe they’ll take that out on us.” If users get angry about what they discover on TrueViews, he added, it means the tool has challenged “their preconceptions in helpful ways.”

While the creators behind TrueViews naturally hope their platform provides politicians and elected officials with the opportunity to better understand their districts and the people they represent, Stephanopoulos and others believe their new platform is a valuable tool for media members and policy advocates as well.

According to Warshaw, the tool enables journalists covering current affairs or local politics to ask questions such as, “‘Do 52% of people in Central Pennsylvania support a border wall?’ We hope this information really gives journalists information that will provide more context for their coverage.”

“I work a lot with groups like the NAACP, the League of Women Voters, Common Cause — my hope is that even if journalists and legislators are not there, that these sorts of [advocacy] groups can bring this data to the council members or state legislators and force it in their faces,” said Greenwood. “By requiring legislative bodies to take notice, voting rights attorneys could more successfully litigate election law cases by ensuring judges and juries have accurate information. Honestly, just putting it into the legislative record, as somebody who litigates this rule of evidence — it’s much easier to get it into court.”

TrueViews is funded by the Bloomberg Center for Cities at Harvard University via the Local Politics Lab at Harvard Kennedy School. GreenInfo Network designed the site.

Want to stay up to date with Harvard Law Today? Sign up for our weekly newsletter.