Of all the issues engendering voter passion in the 2016 U.S. presidential race—immigration, terrorism, Supreme Court appointments—perhaps none has been more surprising than global trade, especially the highly controversial Trans-Pacific Partnership.

“I knew it would be a big election issue, but even I was surprised by the number of ‘No TPP!’ signs at the Democratic National Convention,” says Mark Wu, an assistant professor at HLS, where he teaches international trade and international economic law.

Trade has changed tremendously over the past 20 years, Wu notes: Goods are increasingly manufactured through global supply chains, services play a growing role in economies worldwide, and automation and the digital revolution are upending economic production. With negotiations at the World Trade Organization at an impasse, countries are turning to mega-regional trade agreements like TPP.

The TPP would eliminate tariffs between the U.S. and 11 other nations in the Asia-Pacific region that together make up 40 percent of the world’s economy. President Barack Obama ’91 and Michael Froman ’91, whom the president appointed as U.S. trade representative in 2013, say it will strongly benefit the U.S. by opening new markets and creating high-paying jobs while protecting national security. Although the TPP has minimal Democratic support in Congress, Obama has indicated that he sees TPP as his legacy issue. He has promised to get the agreement passed during the lame-duck session after the November election, using a special “fast track” authority granted by Congress last year.

It may be TPP’s only chance. Both Hillary Clinton (who once supported it) and Donald Trump have made opposition to TPP a campaign issue, as did Bernie Sanders. An unusually broad base stands with them, including labor unions, environmental groups, faith groups, internet freedom groups, farming communities and many in the LGBT community. They say it will increase outsourcing of American jobs and lead to lower wages. U.S. Sen. Elizabeth Warren, a former HLS professor, is among those who especially object to TPP’s Investor-State Dispute Settlement system, which allows corporations to challenge American laws and adjudicate complaints not in American courts but before an international tribunal of three arbitrators.

For insight on the complex issues of the TPP, the Bulletin interviewed HLS alumni who are at the center of the debate.

What would passing the TPP mean to the U.S.?

Michael Froman ’91, U.S. trade representative:

TPP delivers both significant economic and strategic benefits for the U.S. On the economic side, TPP levels the playing field for American workers, cuts more than 18,000 taxes various countries put on made-in-America products, and puts in place historic labor, environmental, and intellectual property standards that ensure that our trading partners play by our rules and values—not China’s. These benefits are particularly important because the U.S. is an open economy. Our average applied tariff is only 1.5 percent, and we don’t put up other barriers to imports. So whether we move forward with TPP or not, imports will continue to come across our borders because our consumers demand them. But through TPP we get the chance to help level the playing field for our businesses and workers in some of the fastest-growing markets in the world. The nonpartisan Peterson Institute for International Economics found that TPP is estimated to increase exports by over $350 billion each year by 2030 and is estimated to create over $130 billion in additional real income each year by 2030, with more than half of the gains going to workers in the form of higher wages.

“Through TPP we get the chance to help level the playing field for our businesses and workers.”

On the strategic side, TPP is the highest-standard trade agreement in history, and it will establish rules of the road to ensure that tomorrow’s global trading system is consistent with American values and American interests.

TPP presents a choice, but it’s not between the status quo and TPP. It’s between TPP and a more statist, mercantilist approach. In fact, right now China is racing ahead to complete RCEP [the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership], its mega-regional agreement that covers 16 markets, from India to Japan. It would carve up these markets at our expense and, unlike TPP, it doesn’t protect worker rights or enhance environmental standards. It doesn’t have strong intellectual property rights enforcement. It doesn’t put disciplines on state-owned enterprises or ensure a free and open internet.

Lori Wallach ’90, director of Global Trade Watch at Public Citizen:

The dirty secret about TPP is that it’s branded as a trade agreement but only six of the 30 chapters have anything to do with trade. It was negotiated behind closed doors for seven years with 500 official U.S. trade advisers who represent corporate interests, and with the press, the public, and Congress locked out.

The reason economists including Robert Reich and Joseph Stiglitz, who supported NAFTA and other past pacts, are against TPP is because there are no trade gains to be had! It involves 11 other countries, six of which we already have zero tariffs with because we already have trade deals with them. … With Japan, their average weighted tariff is less than 2 percent, and of the remaining countries, such as tiny Brunei or New Zealand, there’s just not a lot there as far as new markets for the U.S.

“What’s hiding in there that’s not about trade? Stuff that would make free-trade philosophers roll in their graves.”

So what’s hiding in there that’s not about trade? Stuff that would make the free-trade philosophers like Adam Smith and David Ricardo roll in their graves: patent extensions to create monopolies, stop competition, and keep prices high for medicine and technologies; extensions of copyrights that make textbooks more expensive; limits on internet freedom—things that those industries tried to get done in Congress and failed.

Do you believe President Obama can get the TPP passed during the lame-duck session?

Froman:

The TPP can absolutely pass Congress this year, and the president is far from being alone in his commitment to seeing that it does. There is a large and diverse coalition of support—including mayors, governors, farmers, ranchers, small-business owners, tech companies, military officials and many more—who believe TPP must pass this year. They’re interested in things like how TPP cuts tariffs as high as 38.5 percent on beef exports for the cattlemen in their districts, or how it cuts tariffs as high as 70 percent on made-in-America auto exports. They’re interested in how it renegotiates NAFTA with stronger labor and environment commitments, and how it ensures that the U.S. and not China is writing the rules of trade for the Asia-Pacific region.

Wallach:

It’s 50/50 because the president won’t use fast track to submit legislation unless he has the votes, and right now [September] he does not in the House. So he’s working super hard to get them. They do not want public debate on the TPP because half of the public is unaware of it—after seven years of secret negotiations—but all the polls show that once the public knows about it, they become opponents. So they are dispatching Cabinet secretaries and CEOs to congressional districts to target House members they think they can get to vote for the TPP so they can do this in the lame-duck session under the radar. Do I think they will have the votes in the end? I think they won’t.

Critics say trade agreements exacerbate income inequality in the U.S.—that corporations gain from them but the working class bears the brunt of job losses. Your thoughts?

Froman:

As part of the bipartisan Trade Promotion Authority legislation passed in 2015, Congress commissioned a study from the independent U.S. International Trade Commission to look at exactly this. First, the commission looked at TPP and found that it would deliver an estimated $43 billion in real GDP gains each year by 2032, with two-thirds of that income going to workers in the form of higher wages and additional job opportunities. The ITC report also estimated about $14 billion a year by 2032 of additional purchasing power above and beyond the wage increases, some of which were due to reduced U.S. tariffs on imported goods. The Peterson Institute also has projected that TPP will deliver higher wages, which is consistent with the fact that export jobs pay, on average, 18 percent higher wages than nonexport jobs.

The second congressionally mandated study that the ITC did looked at all modern trade agreements together to see how they have impacted the economy and American workers. What they found was that trade agreements have increased U.S. employment and increased wages. They also found that trade agreements resulted in billions in tariff savings and that a significant part of that savings benefits low- and middle-income consumers. The report also found evidence that trade agreements can serve to reduce offshoring, as U.S. businesses are incentivized to locate production and manufacturing in the U.S.

There is no doubt that forces like globalization and automation have created challenges and economic anxiety. The choice we face is what we do about those forces. We can either yell at the tide as it comes in, or we can proactively shape globalization. High-standard trade agreements, like TPP, are how we shape globalization to make it work for American workers.

Rep. Sander Levin ’57 (Democrat-Michigan, 9th District):

Trade is not the only factor that has exacerbated income inequality, but it is one of them. I urged the International Trade Commission to go beyond its traditional analysis and assess the impact of competition between very different economic structures, including that on income inequality. Their report essentially failed to do so. It determined that TPP could bring about a quite inconsequential growth in U.S. GDP of about one half of 1 percent over many years; at the same time, it came up very short in assessing the impact on growth in jobs, specifically in vital sectors of the American economy, as well as in the growing income inequality in the U.S.

Donald Trump opposes the TPP; Hillary Clinton initially supported it. Now Clinton and Trump say they will seek a better deal than the one that the Obama administration secured on the TPP. If Clinton wins, do you think this will entail making tweaks and then reversing her opposition, as Bill Clinton did on NAFTA?

James Mendenhall ’92, partner at Sidley Austin in the international trade and dispute resolution group, and former general counsel of the USTR:

How would the U.S. feel if all of its TPP partners turned around and now demanded changes?

If Clinton wins, I think she will have to bring home some changes to the agreement. Given what she has said during the campaign, I see no other realistic way forward for her. However, the magnitude of those changes—and how they will be implemented—is unclear. Maybe there will be side agreements, a different type of informal understanding, or something else. The U.S. and its trading partners need to be creative. This will not be easy for our trading partners. They believe they have cut a deal, and that the bargains and compromises have been struck. They may feel that it is unfair to be asked to change the agreement, or that they cannot agree to changes without appearing weak. Frankly, those are all legitimate concerns. How would the U.S. feel if all of its TPP partners turned around and now demanded changes? So, creativity will be needed to meet all of these conflicting demands. But I believe the parties will find a way forward. [These are Mendenhall’s personal opinions and not those of his firm.]

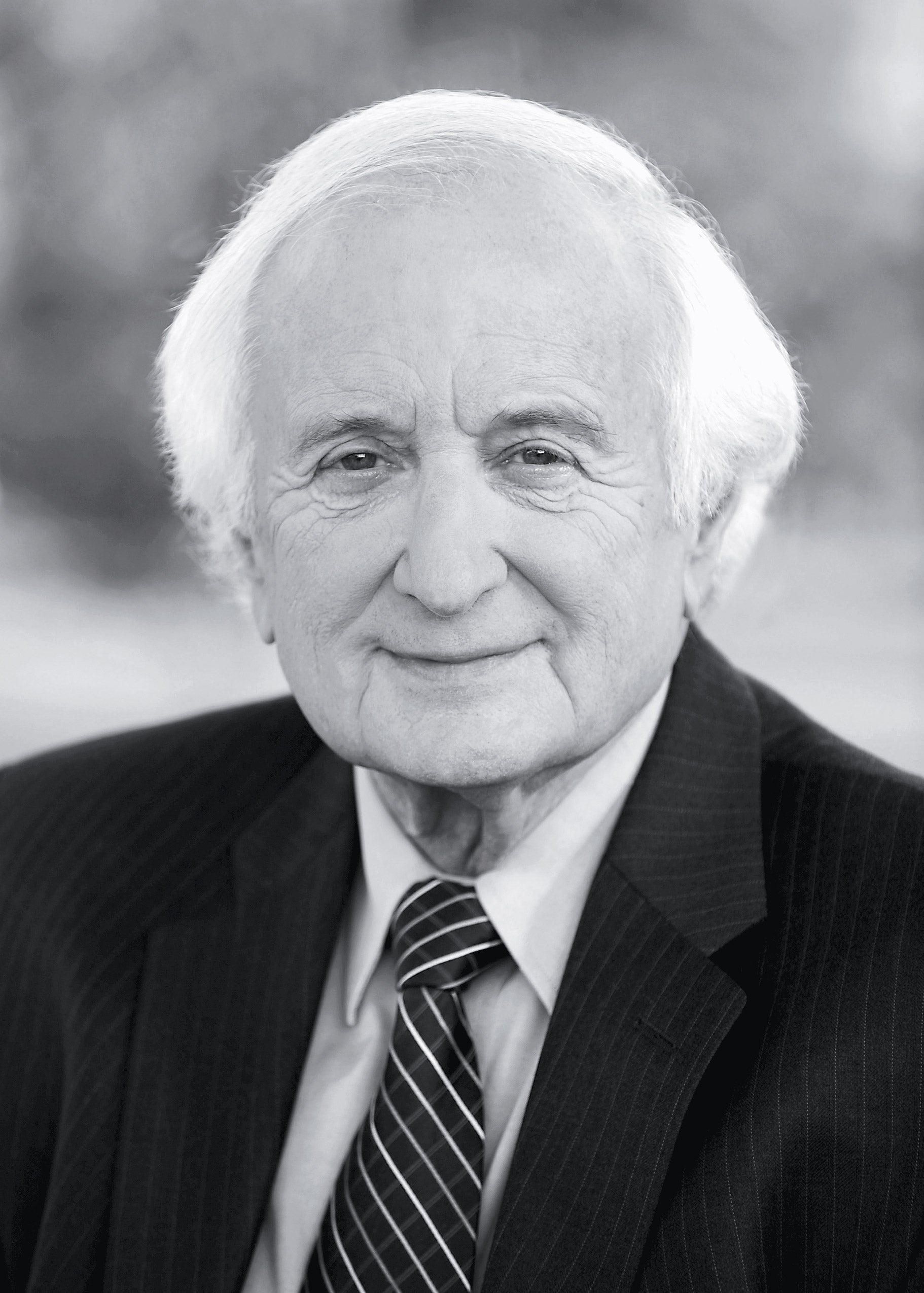

Robert Zoellick J.D./M.P.P. ’81, U.S. trade representative, 2001-2005; former president of the World Bank; and former deputy secretary of state:

The statements of Secretary Clinton and her campaign have become increasingly hostile to TPP. I suspect she will not be able to reverse course for years, until events and messages from the region drive home the economic, political, and security implications of failure. The U.S. government could address some TPP issues through side understandings with other countries without changing the agreement. The Obama administration is working on some of these issues now.

The largest and most controversial issue that might change congressional minds relates to the “manipulation” of exchange rates. The GATT/WTO and IMF articles recognize that currency and exchange rate policies can nullify the benefits of lower trade barriers, but neither institution has been able to address the problem. Some worry whether rules about “manipulation” could be triggered by monetary policies. Fred Bergsten at the Peterson Institute for International Economics has worked on proposals that would establish standards for determining a “manipulator” and has suggested possible remedies, including counter currency intervention. Finance ministers (and central bankers) will not want to deal with exchange rate issues through trade agreements. If a workable set of standards is accepted, however, countries might agree to “norms” of behavior, as G-7 finance ministers have done in the past. Based on the experience of the past 70 years, such a “fix” of a systemic problem has usually first required a combination of U.S. unilateral action and diplomacy.

What are the geostrategic implications of the TPP?

Zoellick:

TPP is seen across Asia as a signal that America’s growing economic interests will be aligned with its security alliances and interests. At a time that many Americans recognize that the application of U.S. military force, however critical at times, cannot solve all international problems, it is a great mistake for the U.S. to retreat from economic diplomacy.

Wallach:

The argument of last resort for every trade agreement, when the economic argument fails, is a national security scare tactic. The foreign policy scare tactic is used to displace the public’s attention from what the trade agreement is really doing for our country: empowering thousands of multinational corporations to sue the U.S. government in front of three corporate lawyers to collect unlimited sums of taxpayer money if they don’t like our laws; making it easier to offshore more U.S. jobs by proving special investor protections; undermining the regulations needed to ensure the stability of our financial system; flooding us with unsafe foods. If you don’t want people looking at that, holler, “China!”

Even worse, TPP could actually harm our national security interests. TPP eliminates language in past trade pacts that authorized the U.S. to protect its own national security interests even if they violated trade pact rules, and to do so without facing trade sanctions. Inexplicably, unlike other TPP signatory nations, the U.S. did not take a national security exception to TPP rules that allow foreign investors new rights to acquire land, firms, natural resources, infrastructure, and other investments in the U.S. and operate them. So if the Committee on Foreign Investment in the U.S. has national security concerns about a foreign company making a U.S. acquisition, that company can drag the U.S. into an extrajudicial investor-state tribunal [the ISDS] that’s empowered to second-guess the U.S. government on what constitutes an essential national security interest and order compensation if that prospective investment is halted.

Kelly Welsh ’78, general counsel, U.S. Department of Commerce:

I don’t think the geopolitical concern is overblown. … It’s fair to say that leaders from other TPP countries—and other Asia-Pacific countries hoping to join the TPP in the future—view TPP as a test of U.S. leadership and of its commitment to the Asia-Pacific region. President Obama throughout his administration has emphasized the importance of the U.S. relationship with Asia to our country’s future. Rejecting TPP would seriously undercut that relationship, and cede influence to other countries in the region.

Levin:

“The primary issue must be, what will be TPP’s impact on Main Street (not on the South China Sea)?”

There are always potential geostrategic aspects related to a trade agreement. But as I have urged regarding all of them, beginning with NAFTA, trade agreements need to stand essentially on their own merits. Congress created the USTR over 50 years ago because it didn’t like how the State Department was allowing foreign policy to influence our trade negotiations. Moreover, in the world today more than ever, I don’t see how a trade agreement can be lastingly in our national security interest if it isn’t in our economic interest. The primary issue must be, what will be TPP’s impact on Main Street (not on the South China Sea)?